The winners of this prestigious award will be identified for the rest of their lives by one of the most winning two-word adjectives in the English language: “Rhodes scholar.” They are one of 32 chosen in the U.S. every year to pursue a degree at the University of Oxford in England, after which the doors to the world’s academic, financial and political centers undoubtedly will open wide for them.

In addition to their outstanding academic achievements, these Rhodes scholars are meant to embody good character, show a clear commitment to others and the greater good, and stand out as strong leaders.

But that last string of requirements is painfully ironic, considering the history of the man behind the scholarship.

Cecil Rhodes is remembered by some as a great British businessman and prominent politician in South Africa—but his true legacy is much darker and one that many British peoples would rather not talk about.

“For much of the century since his death, Rhodes has been revered as a national hero,” wrote Matthew Sweet in an article for The Independent entitled “Cecil Rhodes: A Bad Man in Africa.” “Today, however, he is closer to a national embarrassment, about whom the less said the better.”

As Western civilizations rarely discuss Rhodes outside of scholarship and education, those who live in lands that were once terrorized by the cruel, racist leader see him in a different light.

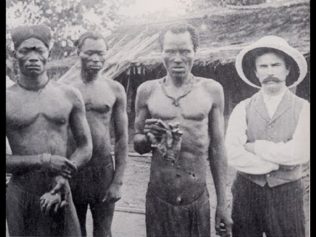

Rhodes both physically and systemically slaughtered Blacks as a part of his mission to obtain more land for the Anglo-Saxon race.

According to Rhodes, Anglo-Saxons were the perfect people and desperately needed to “save Africa from itself.”

In his will he stated that “[Anglo-Saxons] are the finest race in the world and that the more of the world [they] inhabit, the better it is for the human race.”

“Just fancy those parts that are at present inhabited by the most despicable specimens of human beings, what an alteration there would be if they were brought under Anglo-Saxon influence,” his will continued.

Based on the views he shared when he was still alive, there was no questioning who Rhodes considered the “most despicable specimens of human beings.”

According to one essay about Rhodes, the colonialism-obsessed politician once blatantly said that he would always “prefer land to ni**ers.”

To support the claim, Rhodes introduced the Glen Grey Act in 1894, which pushed Blacks from their native lands in order to make way for industrial development.

Much of Rhodes’s true legacy was about displacing African people in order to further benefit the white settlers who were taking over their land.

He then boasted that he could increase employment for the people, but soon revealed his true intentions were not to give the people jobs.

It was to enslave them in their very own land.

Meanwhile, white people from Europe rushed to South Africa and grew their own wealth by stealing gold and diamonds from the land.

The native people were essentially robbed of their freedom and their resources.

Rhodes’s treatment towards people of color forced Dr. C. Magbaily Fyle, a professor of African History at Ohio State University, to describe him as nothing more than a “violent, brutal racist who used forced labor tactics as a means of founding De Beers and other portions of his lucrative success.”

The employment opportunities he boasted about for the African people actually forced them into diamond mines where they were kept away from their families and served only cold tea and bread to eat.

“He has done more than any single contemporary to place before the imagination of his countrymen a clear conception of the Imperial destinies of our race,” The Times wrote of Rhodes. “[But] we wish we could forget the other matters associated with his name.”

The paper went on to say that “empire-builders such as Rhodes” were “enthusiastically admired, on the other hand they are stones of stumbling, they provoke a degree of repugnance, sometimes of hatred, in exact proportion to the size of their achievements.”

While others cringed at the way the natives were being treated, Rhodes found nothing wrong his cruelty.

“The native is to be treated as a child and denied the franchise,” he told the House of Assembly in Cape Town back in 1887. “We must adopt a system of despotism in our relations with the barbarians of South Africa.”

In the midst of Rhodes’s plans for expansion, he eventually seized land that would bear his own name and uphold his own racist beliefs.

Rhodes’ British South Africa Company acquired the land formerly known as Rhodesia in the 19th century and made sure a predominantly white government ruled over the land.

Of course, to even acquire the land he had to slaughter an entire population of African natives.

Rhodes paid a mercenary army from England and provided them with all the weaponry they needed before sending them on a mission to wipe out the land of the Matabele and Shona.

Historians predict the army only had five machine guns, but that was enough to slaughter roughly 5,000 African people in one afternoon alone.

The amount of value Rhodes and other Englishmen placed on the lives of these natives was made clear when they celebrated the genocide with a hearty meal and champagne.

The true depth of Rhodes’ racist and cruel tactics proved to be enough to fill many academic journals and historical books today—the same articles and books that many people of Western civilizations tend to shove to the back of their minds.

Rhodes was a man who stole close to a million square miles of territory from the African people and was far from satisfied with the sheer amount of land he acquired.

He famously uttered that he would “annex the planets” if he could.

So in a cruel twist of fate, the same man who was admired by the socialist author Oswald Spengler and one of history’s cruelest dictators, Adolf Hitler, is now the same name given to scholars who are meant to possess good moral fiber and a desire to contribute to the greater good.

With the 2015 class of Rhodes Scholars, including five Black students, the twisted irony continues as the trust started by a man who robbed their ancestors of land, resources and, in some cases, their lives, will now be the man credited for giving them the chance to further their own education and open them to a world of career opportunities they may have never seen otherwise.

Not to mention, the ultimate irony is that Rhodes would never even dream of granting these Black students such opportunities if he were still alive today.