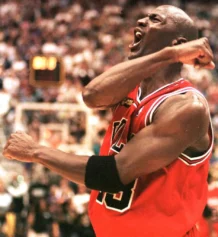

Seventeen years ago, right around this time of year, just after Christmas, I chatted with Michael Jordan in the visiting locker room at the Atlanta Hawks’ old home, the Omni. Me and the G.O.A.T.: Greatest of all time. One-on-one.

He was still destroying the competition in what would be his final year with the Chicago Bulls. (And he blasted the Hawks that night, too.) Among other things, I asked him about his plans after his legendary career. I asked him about owning an NBA team.

Jordan looked at me with those eyes that helpless defenders probably saw in their nightmares.

“No way,” he said. “I don’t want to deal with these (young players). I don’t need the headache.”

Well, all these years later, Jordan has a headache, and a big one. He obviously changed his mind since that day we talked. He’s owner of the Charlotte Hornets, the only Black majority owner in the NBA, and while things are flourishing on the business side for the franchise, it’s on the court that people see. And what they see is Jordan’s headache playing out in front of them.

The Hornets are 4-14 in the Eastern Conference, where there is room to make a move. Jordan wants better. He needs better. His track record as an NBA executive is deplorable. He became president of basketball operations for the Washington Wizards in January 2000, and his tenure was less than stellar.

People forget that he removed the stifling salary of Juwan Howard off the payroll and discarded Rod Strickland in his youth movement that bore spoiled fruit. Until Jordan does something big—really big—his executive legacy is that he drafted Kwame Brown out of high school with the No. 1 pick in 2001.

Brown was a disaster, one of the all-time NBA busts for a top draft selection. Jordan continues to carry that mark with him. And what the Hornets are doing now is not helping.

But Jordan being Jordan, he told ESPN.com this:

“I’ve always considered myself a very successful owner that tries to make sound decisions. And when you make bad decisions, you learn from that and move forward. I think I’m better in that sense. I’ve experienced all of the different valleys and lows of ownership and successful business. If that constitutes me being a better owner, then I guess I am.”

That’s one way of looking at it. Another is that success can be measured by wins and his teams have provided far too few.

He’s trying, though. Jordan sits on the bench during home games and berates officials, when he sees cause. He believes his presence so close to the team is inspiring. It might be, but it takes some getting used to.

“The first time I saw him on the bench, though, was when I was rookie. I was nervous,” point guard Kemba Walker said to ESPN.com. “I couldn’t catch the basketball. And when you come out of the game, it’s the longest walk back to the bench in the world sometimes, because you see the greatest player to ever play the game sitting right there looking at you. As time goes on, you get used to it.”

Jordan does not want to get used to the losing. On the court, where he could physically influence the outcome, he was a six-time champion, the ultimate winner. He has acquired some sound talent to reverse his and the franchise’s fortunes: Walker, Al Jefferson and Lance Stephenson this summer.

“M.J. and those guys have done their jobs. We just have to get better,” Jefferson said to the website. “I’m not a psychic, my man. I’m not in panic mode. I’m not the type of guy who sits back and makes excuses for things going bad. We have the talent. We just have to get it together. Once we do, we’ll be having a totally different conversation.”

And Jordan’s headache that he feared 17 years ago can finally ease.