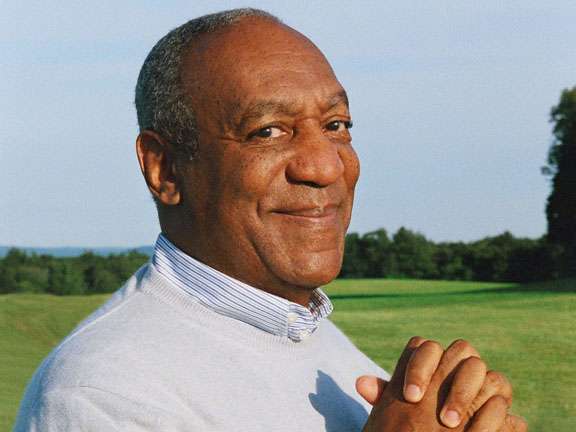

Talk about a slow fall from grace. Two decades ago, The Cosby Show debuted on national TV, vaulting its star, Bill Cosby, into the role of America’s most lovable dad. But look at him now.

The 77-year-old comedian, who performs this Saturday at Carnegie Hall as part of the New York Comedy Festival, is enduring a heated backlash, ignited in part by one of comedy’s brightest lights, Hannibal Buress. Chicago-native Buress, 31, known for his meandering story-telling filled with non-sequiturs and sharp social commentary, performed a standup routine early this month, referencing Cosby’s rich history of rape allegations.

The accusations date back almost a decade, to accusations levied against the comedian in 2005 by a Temple University student who said Cosby drugged her and raped her in his mansion. The woman’s lawyers were able to find 13 other women willing to testify under oath that they suffered similar abuse. [Cosby denied any wrongdoing and the case was settled out of court]. Then, earlier this year, yet another woman told Newsweek magazine that Cosby had assaulted her on numerous occasions when she was a teenager.

In his routine, Buress pointed out Cosby’s apparent hypocrisy: “Bill Cosby has the fu**ing smuggest old Black man persona that I hate. He gets on TV, ‘Pull your pants up Black people …’ Yeah, but you rape women, Bill Cosby, so turn the crazy down a couple of notches.” The YouTube video of that performance has since gone viral.

For years, the rape accusations against Cosby lay dormant, seemingly destined to become a he-said she-said footnote to his career. Then Buress stepped to the mic and pointed out the obvious. In a way, the swift response to Buress’s mere mention of rape only underscores how difficult it is for women, especially Black women, to be heard when they accuse a powerful man of sexual violence.

As the Washington Post notes, “It wasn’t enough that 13 different women accused Cosby of drugging, raping and violently assaulting them. It was only after a famous man, Burress, called him out that the possibility of Cosby becoming a television pariah became real.”

Of course, Black audiences have long had a strained relationship with Cosby. In the beginning, we applauded him as a trailblazer — Cliff Huxtable offered an image of Black middle-class domesticity never before seen on network TV — but even then there were critics. Social activists charged Cosby with presenting a false vision of a color-blind America: How can we fight systemic racism if you keep acting like it doesn’t exist? And then came the rape allegations, followed quickly by Cosby taking up the crusade of respectability, admonishing young Black men to stop complaining and pull up their pants, even as they were being shot dead in the streets.

In the wake of Buress’s pointed critique, Cosby’s appearance on the Queen Latifah Show was cancelled (reps from the show were quick to point out that it was the comedian who backed out of the engagement). Some question whether NBC will move forward with the Cosby-helmed sitcom they have slated to hit the airwaves later this year.

A lot has changed in the decade since Cosby was first accused of rape. Social media now allows regular people to hold even the most powerful celebrities accountable for dirt a good lawyer used to make disappear. Buress may have intended to call out Cosby for being a hypocrite, but he’s ignited a conversation that’s long overdue: If a celebrated cultural icon is not what he appears, should we still love him or leave him alone?