Thomas Eric Duncan, the first person diagnosed with the Ebola virus on U.S. soil, has died, sparking tons of controversy surrounding his treatment.

The 42-year-old man from Liberia is not the first person to be treated for Ebola in the U.S.

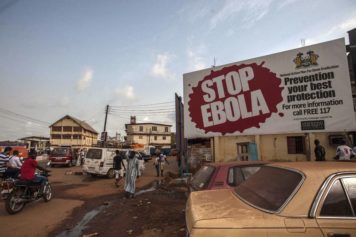

Prior to Duncan contracting the virus, three white Americans contracted the illness while working in West Africa, which is facing what is perhaps one of the worst Ebola outbreaks in history.

Dr. Kent Brantly, Dr. Richard Sacra and aid worker Nancy Writebol are still alive after receiving experimental “miracle” drugs that may have a chance of curing the Ebola virus.

Brantly and Writebol were treated with a drug known as ZMapp, which was never given to Duncan.

Sacra was treated with a different drug called TKM-Ebola.

Instead of Duncan being another success story for either of the experimental drugs, he was pronounced dead around 8 a.m. Wednesday at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital in Dallas.

He was kept in isolation at the hospital since Sept. 28.

Hospital spokesman Wendell Watson said officials were left with “profound sadness and heartfelt disappointment” after Duncan passed away.

Despite their claims of being disappointed and saddened by the loss, many wonder if everything was done to save the Liberian native’s life.

While white Americans took their journey on the road to recovery with ZMapp or TKM-Ebola, Duncan was treated with brincidofovir.

The decision to use this drug rather than the other more successful experimental drugs left some medical experts scratching their heads.

Thomas Geisbert, who developed TKM-Ebola, said he was confused by the hospital’s decision.

“I’ve never heard of this drug being used for Ebola before,” he told USA Today. “It works in cell culture. That’s great. Lots of things work in cell culture against Ebola.”

He then explained that while the vaccine worked in “cell culture” it failed to save any of the animals that were diagnosed with the virus.

Earlier this week, even Duncan’s family questioned why he was not being treated with the ZMapp drug.

Then there appeared to be two different explanations about why Duncan was not treated with ZMapp.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Tom Frieden told reporters that Duncan’s condition was too poor to use ZMapp, which has been known to cause flu-like side effects.

Shortly afterwards, however, another explanation surfaced via Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health.

On Sunday’s episode of Face the Nation, Fauci said the supplies of ZMapp had been depleted and there was none left to treat Duncan.

Many grew skeptical of the two different explanations and conspiracy theories spread like wildfire.

Not only was Duncan’s treatment suspicious, but his diagnosis was bizarre.

When Duncan first sought medical attention on Sept. 25, he was given antibiotics and sent home.

The hospital admitted that Duncan revealed he had recently returned from West Africa.

Despite Duncan exhibiting symptoms of Ebola and disclosing information about his travels to West Africa, he was sent home as if he had nothing more than a common cold.

During that time he came in contact with at least 50 people.

According to the CDC, only 10 of those people have even a moderate risk of contracting the disease and none of them have shown any symptoms as of Sunday.