But there is a risk that the intense Western reaction to Ibrahim’s case might undermine local efforts to secure her release. In the days immediately following the sentence, reporters from Sudanese TV channels went out on the streets to gather vox pops asking people what they thought of the judgment. Many opposed it.

Others were incredulous, finding it hard to believe that such a case could even make it to the courts. People assembled outside the court buildings chanting support for Ibrahim and calling for religious freedom. TV discussions and newspaper columns took up the apostasy debate, and in private gatherings her plight dominated conversation. The case has forced a national self-examination and appraisal of the version of Islam the Sudanese want to practice, and, more important, has boosted support for the view that religion is a personal matter.

But as international media attention has intensified it has eclipsed this internal dissent, which arguably has a better shot at securing Ibrahim’s release. Inevitably it has resulted in predictable Sudanese preciousness over sovereignty, which risks hijacking the initially healthy national deliberation about Sharia law. Indeed, the Sudanese government was so alarmed by the force of the backlash that it attempted to ban any comment on the case in the media.

For a chippy, isolated and belligerent regime, saving face is more important than saving lives. Moreover, the details of the case have been misreported in much of the Western press, particularly the claim the death sentence was for marrying a Christian, when it was for the charge of “reversion” from Islam. British Prime Minister David Cameron’s condemnation in particular went down very badly in Khartoum. The wisdom of a private phone call – a sensitivity often extended to, say, Saudi Arabia or Bahrain – has been absent.

There is now a risk of the Sudanese losing ownership of their own cause, one that goes to the heart of the tension between conservative religious values and a lack of appetite for heavy-handed state execution of religious law. There is an increasing awareness of, and frustration with, the Sudanese authorities’ hypocritical application of Islamic law, one that has been increasingly lax over the past few years.

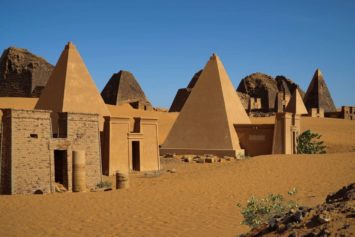

If you were to visit Khartoum knowing nothing of the country except these tales of religious fundamentalism, you would be surprised and confused. Men and women mingle freely on public transport and in cafes, and dance together at wedding parties. Sudan has historically practiced a softer, Sufi, spiritual form of Islam, one that finds an easy rhythm with the country’s unique Afro-Arab traditions.

Read the full story at theguardian.com