But the defensiveness of Western nations over their involvement in the massacre is still fresh, as evidenced by the reaction of the French government after Rwandan President Paul Kagame told the magazine Jeune Afrique that both France and Belgium—Rwanda was former Belgian colony—had a direct role in the “political preparation for the genocide.”

Kagame also accused France of being involved in the slaughter of Rwandans who tried to escape through an area controlled by the French.

Outraged French officials responded by announcing that Christiane Taubira, France’s justice minister, would not attend today’s ceremonies in Kigali, the Rwandan capital, “under these conditions.”

As noted in an op-ed in the Christian Science Monitor by professor Margee M. Ensign, president of the American University of Nigeria and co-author of “Rwanda: History and Hope,” and Mathilde Mukantabana, the ambassador of Rwanda to the United States, this latest contretemps comes at a delicate time for France.The European nation is in the midst of trying to stop violence in the Central African Republic, where thousands have been killed and nearly 1 million people—almost the entire Muslim population—have fled their homes to escape the kind of violence that many fear could easily escalate into the sort of unspeakable carnage that took place in Rwanda 20 years ago.

“It’s a long and complicated relationship between the two countries [France and Rwanda],” Carina Tertsakian, a senior researcher on Rwanda and Burundi for Human Rights Watch in London, told the Monitor. “The whole of the international community bears a responsibility for not stopping genocide in 1994, but France’s responsibility went beyond that because it had supported the previous government that perpetuated the genocide and had trained their soldiers.”

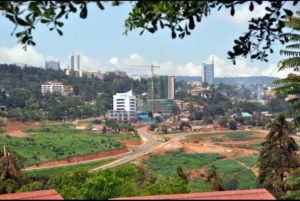

But as Rwanda recognizes the tragedy that occurred in 1994—U.S. President Bill Clinton has said his decision not to stop the massacre was one of the biggest regrets of his presidency—the nation has shown remarkable resiliency in rebuilding its economy and the trust of its people.

Using the power of their historical institutions like gacaca—a traditional conflict resolution process of community trials—and imihigo, a performance contract between leaders and citizens, the nation has been able to reverse its fate. After the slaughter, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda tried 58 cases, at a cost of more than $2 billion, according to Ensign and Mukantabana. But the gacaca community courts tried over one million people implicated in the killings, at a cost of only $25 million.

According to scholar Zachary Kaufman, gacaca and the other transitional justice initiatives have “helped to transform Rwanda’s culture of impunity into one of accountability.” In addition, using the imihigo contract, there has been a major increase in citizen participation and accountability at the local level, creating a new level of peace, reconciliation, and development.

“Amid criticisms of what they say is the Kagame government’s authoritarianism and problematic involvement in conflicts in the greater region, too many Western observers have missed this vibrancy and innovativeness of Rwanda’s emerging democracy,” Ensign and Mukantabana concluded. “And they fail to see how it has contributed to undeniable progress in education, health, gender equity, and economic growth in the country.”