Hepatitis C is an infectious disease that affects the liver and is caused by the hepatitis C virus (HCV). The infection is often asymptomatic, but chronic infection can lead to scarring of the liver and ultimately to cirrhosis, which is generally apparent after many years. In some cases, those with cirrhosis will go on to develop liver failure, liver cancer, or other life-threatening complications.

It is spread primarily by blood-to-blood contact and has been associated with intravenous drug use, poorly sterilized medical equipment, and transfusions. HCV is more infectious in the blood than the AIDS virus.

Since 1991, the standard treatment for hepatitis C was interferon. This treatment requires medication by injection for nearly a year and can have severe side effects such as flu-like symptoms, fatigue, anemia, and depression. The average cure rate is 45 percent for those with hepatitis C, genotype 1, the most common strain.

The new drugs, Simeprevir (sold as Olysio by Janssen Therapeutics, a division of Johnson & Johnson) and Sofosbuvir (marketed as Sovaldi by Gilead Sciences) have had a 95 percent cure rate in clinical trials. Patients take a pill, usually every day for 12 weeks, and they have mild side effects.

However, the downside is the cost – the average interferon treatment was about $15,000 to $20,000, or a fraction of the price for these new drugs. Health insurance companies, state health departments and consumers are trying to decide who should pay the new monstrous bill.

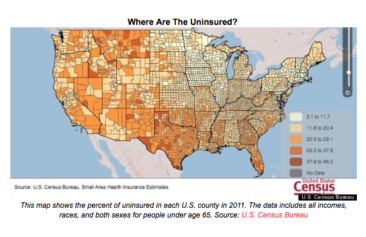

It is unclear, policy-wise, how states will handle this situation. Hepatitis C patients are disproportionately on Medicaid, with the average income less than $23,000 a year, according to the CDC’s report published March 4, in the Annals of Internal Medicine. Even to treat a fraction of the patients could add billions to the budget.

“I don’t recall any other situation in which we’ve had very effective, very expensive drugs come out for an important condition with such a large patient population potentially eligible for treatment,” said Steven Pearson, president of the Institute for Clinical & Economic Review, a forum of policy makers and scholars, who are also reviewing the new hepatitis C treatments.

“If you do back-of-the envelope calculations, it’s clear budgets couldn’t take on the potential of every eligible patient,” Pearson told USA Today.

U.S. health officials have recommend that all baby boomers born between 1945 and 1965 be screened for the virus, estimating that more than 2 million of them may be infected.

S.C. Rhyne is a blogger and novelist in New York City. Follow the author on twitter @ReporterandGirl or on Facebook.com/TheReporterandTheGirl and visit her website at www.SCRhyne.com