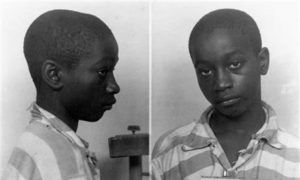

An all-white jury took barely 10 minutes to convict George Stinney of bludgeoning the girls, aged 11 and seven, in the segregated town of Alcolu. He was electrocuted just 84 days after the crime, as the youngest person to be executed in the U.S. during the 20th century, according to the Death Penalty Information Centre.

Steve McKenzie, the lawyer acting for Stinney’s family, filed the trial request in Clarendon County, claiming that the teenager’s conviction was based on a forced confession and a racially divided community’s desire for revenge. Analysts say the motion is largely symbolic, and faces little chance of success because of strict state rules that largely prohibit the introduction of new evidence after the conclusion of a trial.

But family members say that just getting the case back into a courtroom after seven decades will be a victory in itself.

“His family is still thriving, but his soul is not at rest,” said Irene Hill, Stinney’s second cousin. “It has been 69 years now, and there still is no justice. There has been no justice for George, nor for those two young girls, because we know that he is innocent.”

The bodies of June Binnicker, 11, and Mary Emma Thames, seven, were found in a creek on March 25, 1944, after they were reported missing while picking wildflowers the day before. Both were stabbed to death with a railway spike.

A town resident said he saw Stinney, who was playing outside with his younger sister, talking to two young girls. He was arrested and put on trial one month after the girls disappeared, with the entire case lasting only two and a half hours and the teenager represented by a court-appointed lawyer who called no defense witnesses.

McKenzie’s motion, which says Stinney weighed only 90 lbs. and would have been physically unable to commit the crime, contains sworn statements from two of his siblings, who say he was with them throughout the day the victims went missing.

Charles Stinney, who was 12 at the time, explained in the new court filing why his family did not co-operate with investigators after the murders.

“George’s conviction and execution was something my family believed could happen to any of us in the family. Therefore, we made a decision for the safety of the family to leave it be,” he wrote.

Read the full the story at theguardian.com.