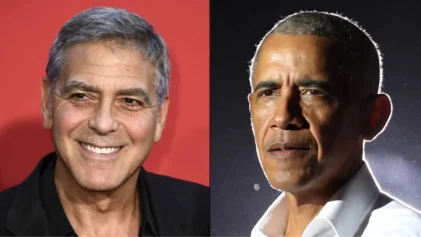

When President Obama steps to the podium today to deliver a speech marking the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington and Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech, he will be gently balancing a dizzying array of divergent agendas: from the African-American community yearning for him to directly address the persistent problems of racial discrimination, from other minority groups hoping that they aren’t left out of his equation for progress, and from conservatives hungrily seeking more ammunition with which to predict that his most ardent wish is to direct a black takeover of America.

Ever since Obama walked into the White House briefing room after the George Zimmerman acquittal for killing unarmed teenager Trayvon Martin and spoke about the slings and arrows regularly encountered by black males in America—including himself—there has been a steady wave of debate, commentary and attack surrounding race and the president.

So as he ponders what he might say to the world on this august occasion, surely Obama is considering just how powerful and symbolic—and how much of a lightning rod—it is when he talks about race.

In providing previews of the president’s speech, aides said he will celebrate the progress that has been made, thanks to the civil rights movement, but also point to the work that still must be done to realize King’s dream of racial justice in America.

The aides say that work includes fighting to protect voting rights and building what the president calls “ladders of opportunity” for poor people of all races.

While Obama hasn’t spoken frequently about race as president, he addressed the subject directly and eloquently throughout his book, “Dreams from My Father.”

Scholar Michael Eric Dyson noted that that Obama’s silence on race after writing such an insightful book was akin to Michael Jordan ending his basketball reign in his prime.

NPR reports that when an African-American professor asked the president last week during a college visit in New York where he thinks the country is in terms of civil rights, Obama said, “Obviously, we’ve made enormous strides. I’m a testament to it. You’re a testament to it.”

But he added that discrimination has not disappeared and, while it’s nothing like it was 50 years ago, the legacy of Jim Crow has left lasting barriers to success.

“There are a lot of folks who are poor and whose families have become dysfunctional because of a long legacy of poverty, and live in neighborhoods that are run down and schools that are underfunded,” he said.

But not all observers are eager to hear Obama talk about race again.

“I don’t think that the racial climate in this country is helped when the president wades in to what are always turbulent racial waters and stirs things up, which is what he did,” Abigail Thernstrom, a member of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, who was appointed by President George W. Bush, told NPR.

But Democratic pollster Cornell Belcher said the resistance to frank talk about race among whites is one reason the country hasn’t made more progress.

“It’s a conversation that makes a lot of white America uncomfortable and they would rather not have,” says Belcher. “And understand, they have not had to have the conversation.”

NPR predicted that when he speaks today, Obama will talk about civil rights in broader terms, encompassing not just blacks and whites, but Latinos, women and gays—as he did in his second inaugural, when he spoke in one breath of Selma, Stonewall and Seneca Falls.

“Because times have been tough, because wages and incomes for everybody have not been going up, everybody is pretty anxious about what’s happening in their lives and what might happen for their kids, and so they get worried that, well, if we’re helping people in poverty, that must be hurting me somehow,” the president said. “It’s taking something away from me.”

Obama said to the college professor in New York, according to NPR, that “it’s in all of our interests” to lift up poor communities and help young people succeed — the same causes King espoused 50 years ago.

Obama met with prominent African-American religious leaders on Monday at the White House and again at a reception yesterday, during which he mused about the nation’s progress on civil rights—and how much more work needed to be done.

“He was discouraging us from comparing him to Dr. King,” Rev. Alvin Love of Chicago, one of the preachers who was there, told the New York Times.

The Times noted King has been an idol, but also a “burden” to Obama during his presidency.

“He is a politician juggling multiple constituencies, not a preacher leading a movement,” the Times wrote. “He is a president on the verge of a new war in the Middle East, not a peace activist extolling nonviolence. He has spent nearly five years in the White House wrestling with his own identity and the essential tension between his barrier-breaking role and his fundamental desire to be judged like any other president.”

“He sees it as a very different role at a very different period of time,” said Valerie Jarrett, his close friend and senior adviser. “Martin Luther King was a preacher, a civil rights leader.” While the president often says he “stands on their shoulders,” she added, “he felt the responsibility to pick up the baton, not as a civil rights leader but as a president of the United States.”

Rev. Al Sharpton, a friend of the president who was in the White House meeting on Monday, said Obama should not ever be equated with civil rights pioneers.

“In the African-American community and in the media they project him as the new Martin Luther King,” he said in an interview. “But he’s the new John Kennedy. A president shouldn’t dream. A president should legislate and guide.”

But frequent Obama critic Tavis Smiley told the Times that the president has been “timid” and “almost silent” on the very issues King addressed.

“If you’re not going to address racism, if you’re not going to address poverty, if you’re not going to address militarism, if you’re going to dance around all three of them, then you’re not doing justice to Dr. King, and you might as well stay home,” Smiley said in an interview.