Scholars from three continents gathered at Harvard University recently to parse the Emancipation Proclamation, the earth-shaking 1863 executive order from the Lincoln White House that proclaimed all slaves in the rebellious South “forever free.”

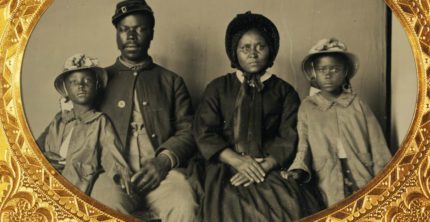

It helped break the back of the Confederacy, gave the war its moral center, and rejuvenated federal forces starved for new regiments. (By the end of the war, about 180,000 black soldiers had served — 10 percent of the Union army.)

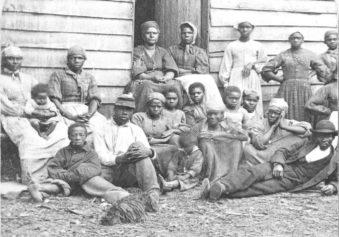

But for a century afterward, the proclamation also represented a historical irony: Until the 1960s, arguably, generations of American blacks were re-enslaved socially and economically by a recalcitrant South and a forgetful North.

On May 2-4, “Freedom Rising” expanded the celebration of this epic moment 150 years ago. It grappled with the facts of African-American service during the Civil War. It also explored the emotional antecedents of that service in what is now called the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). (Led by Toussaint Louverture, that conflict created the hemisphere’s first black state. It also inspired a cascade of 19th-century slave rebellions.)

Among the sponsors of “Freedom Rising” were Harvard’s W.E.B. Du Bois Institute, the Charles Hamilton Houston Institute for Race and Justice at Harvard Law School, and the National Park Service’s Boston African American National Historic Site.

Stars in the firmament of Civil War scholarship were drawn to the event. Eric Foner, a Pulitzer Prize-winning historian from Columbia University, delivered “Lincoln, Emancipation, and African-American Soldiers,” the May 2 keynote address, at the Museum of African American History on Joy Street in Boston.

The African Meeting House there, built in 1806, was the site of the founding of the New England Anti-Slavery Society in 1832. By 1863, it was also the main recruiting site for the storied 54th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, which was among the first black units assembled during the Civil War.

On May 3, Yale University’s David Blight delivered remarks at a public symposium. Blight’s “Race and Reunion: The Civil War in American Memory” (2001) is regarded as a classic study of the war’s aftermath — which included, he wrote, “the attempted erasure of emancipation from the national narrative.”

Read More: harvard.edu