What did freedom look like? asked Deborah Willis and Barbara Krauthamer ,when they set out to compile the impressive tome “Envisioning Emancipation: Black Americans and the End of Slavery,” a photographic history of the African- American journey from slavery to emancipation during and after the Civil War.

Published to coincide with the 150 anniversary of emancipation this past January, the book highlights 150 rare photographs that show slaves and formers slaves as dignified, beautiful, and full of pride —imagery not often emphasized when exploring the era. Krauthamer answered questions about what these photographs reveal about the time of slavery, and America as a nation.

African American soldier in Union uniform with wife and two daughters; Photographer unknown, 1863–1865

Q: You went through over 1,000 photographs. How did you select the ones to use in the book?

KRAUTHAMER: We looked at photographs from all over the country in museums, libraries, the Library of Congress, university archives, private collections. We were looking for images that we thought really illuminated our central question: “What did freedom look like?” We wanted to show a range of experiences from the 1850s when black and white abolitionists were involved in the anti-slavery fight through the early 20th century to think about what freedom looked like to generations after emancipation — how the legacy of emancipation was remembered and preserved.

Studio portrait of an African-American sailor; Photographer: Ball and Thomas Photographic Art Gallery, 1861–1865

Susie King Taylor; Photographer unknown, 1902

Q: Were you surprised by any of the photographs that you came upon?

KRAUTHAMER: One of the things we were struck by were certain continuous themes that we saw from the 1850s through the 1960s: those of dignity, pride and perseverance, sometimes in the most oppressive of times in the United States.

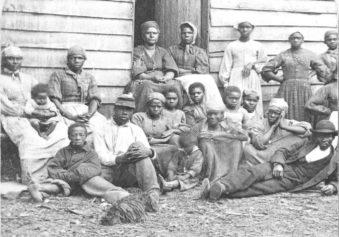

Whole family at the Hermitage, Savannah, Georgia; Photographer unknown, 1907

Q: The book was inspired by this image of a woman named Dolly whose photograph was on a wanted flyer. Her owner was trying to get her back, and you tried to uncover her story.

KRAUTHAMER: Yes, we don’t know why the photograph was taken, but it’s attached to a handwritten notice because Dolly freed herself by running away in 1863. Her master wrote this notice offering a reward for her return, put her photograph on it, and saved that notice long after she was gone, and the war had ended and slavery was abolished. He was still clinging to this image of her, and she had gone off and made her own life far away from him…

Read More: good.is