The military conflict in Mali has now entered a new phase: Find the Islamists in the mountains and kill them.

Since French President Francois Hollande sent 4,000 French troops into the northwest African nation on Jan. 11 to join with the Mali army, they have primarily been engaged in taking the major central and northern cities back from the Islamist rebels. But now that the cities have been retaken and the rebels have mostly fled into the northern mountains of the Sahara, the task of locating them has become much more difficult.

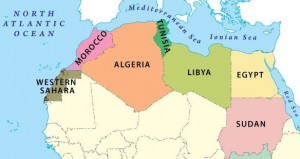

Before the French arrived, the Islamists were rampaging through Mali, with reports of horrific human rights abuses and rapes committed by the rebel soldiers and widespread fears that the conflict would create hundreds of thousands of new refugees fleeing the turmoil to surrounding countries. Refugees interviewed by U.N. workers described an extremely disturbing and confounding interpretation of Islamic Sharia law. In a report by the U.N. Human Rights Council, a case is cited of a 22-year-old woman raped by six armed men for not wearing a veil in her home — leading one to wonder how a strict reading of Islam could conclude that sexual violence was the proper response.

Using the French to root out the rebels is particularly difficult because they are so unfamiliar with fighting in the rocky terrain, which is similar to the challenges the U.S. military faced in the mountains of Afghanistan.

The attention of the French and African forces is now focused on the Adrar des Ifoghas, one of Africa’s harshest and least-known mountain ranges, according to the New York Times. They are trying to rely on soldiers from Chad, more familiar with desert warfare, who left Kidal on Thursday to make a run at the rebels deep into the Adrar. In addition, the French carried out about 20 airstrikes in recent days in those mountains, including attacks on training camps and arms depots, officials told the Times.

“These mountains are extremely difficult for foreign armies,” said Backay Ag Hamed Ahmed of the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad. “The Chadians, they don’t know the routes through them.”

The mountainous region, consisting of grottoes and rocky hills, has long been used by Tuareg nomads from the region and more recently for extremists from Al-Qaida in the Islamic Maghreb.

African forces are likely to be assigned the brunt of the combat operations, going “from well to well, from village to village,” said Gen. Jean-Claude Allard, a senior researcher at the Institute for International and Strategic Relations in Paris.

“The terrain is vast and complicated,” Col. Michel Goya of the French Military Academy’s Strategic Research Institute told the Times. “It will require troops to seal off the zone, and then troops for raids. This will take time.”

There is also disagreement about how many rebels remain, after hundreds have been killed by the French and African forces. The estimates range from a few hundred fighters to a few thousand, who have spread out in the region. The French are trying to find them all, knowing that any left behind could become the terrorist or suicide bomber who commits maximum havoc with a single bomb. This was illustrated earlier this week in Gao, when a suicide bomber approached the checkpoint at the entrance to Gao at around 6 a.m., riding a motorcycle and wearing an explosive belt. He blew himself up before he reached the checkpoint — the first suicide bombing since the French moved into Mali on Jan. 11.