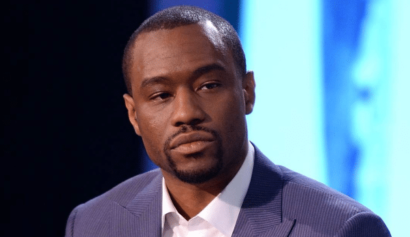

Drew Brown had several admission offers from prestigious doctoral programs across the country when he decided two years ago to further his graduate study.

But Temple University’s doctoral program in African-American studies quickly rose to the top of his list. Its esteemed faculty members, coupled with the school’s reputation as the first degree-granting doctoral program in African-American studies in the world, appealed to this native from Windsor Ontario, Canada, who has plans to one day become a university professor.

“It just seemed like a natural fit,” says Brown, whose mentor, Dr. Daniel Black—a rising academician at Clark Atlanta University—also earned his Ph.D. in African-American studies from Temple. “Students and graduates are doing cutting-edge research and scholarship.”

Now, halfway into his second year at Temple, Brown says that he’s deeply concerned about the program’s reputation, claiming that the university has actively taken steps to undermine the department’s self-efficacy. He and members of the Organization of African American Studies Graduate Students recently sent an open letter to the school’s president, provost and board of trustees, complaining about the administration’s treatment of the department, which has about 30 graduate students and more than a hundred undergraduate majors.

Among their chief complaints is the decision by Dr. Teresa Soufas, the dean of the College of Liberal Arts, to place the department in university receivership, meaning it had to relinquish control of the department to an external authority, earlier this year. Soufas appointed her vice dean, Dr. Jayne Drake, as the interim chair to run its day-to-day operations, which includes overseeing its seven full-time faculty members. The move came after Dr. Nathaniel Norment retired in July after serving as chair of the department since 2001.

Administrators at Temple say that it was an effort to help the department refocus on recruiting more majors and strengthening its course offerings, but others saw the move as a top-down approach by a White dean to strip a department of its governance structure.

“One could easily draw the impression that the dean is trying to get rid of the department,” says Dr. Molefi Kete Asante, who founded the doctoral program in 1988 and is one of the nation’s foremost scholars on Afrocentrism. “In fact, she arbitrarily split a line between the history department and the African-American studies department, which had never happened before. This was an African-American studies line that was split, and therefore, students and faculty could get the impression that we were losing positions and autonomy.”

Read more: Jamal Watson, Diverse Education