It’s not all that hard envisioning Joe Biden reprising his role as Vice President for another four years.

Now try imagining him doing so under President Mitt Romney.

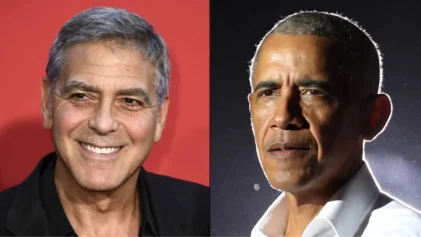

Such a scenario is extremely unlikely, but it could happen under the complex U.S. system for selecting presidents. A 269-269 tie between Romney and Barack Obama in the Electoral College, the body set up to formally choose the president, would trigger fallback mechanisms that might leave the country in a constitutional and political tempest.

According to the 12th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, a tie would bump the choice to the newly-elected Congress. It’s all but a certainty that the House of Representatives remain in Republican hands, meaning that legislative body would choose the president, while the Senate, likely to remain controlled by Democrats, would select the vice president.

“If you stipulate that they act according to partisan interests, they would pick Biden even if the House has picked Romney,” said Edward Foley, director of the election law program at Ohio State University’s Moritz College of Law in Columbus in a Bloomberg report.

A Romney-Biden administration would perhaps be the oddest potential outcome to what could be a testy finish to a heated presidential election.

In the U.S. system, voters do not directly select their president when they submit their ballots, but instead choose 538 electors who are mostly allocated on a statewide basis.

Those 538 electors then cast ballots in the Electoral College, with the winner claiming at least 270 of those elector votes.

In case of a tie, the new House would choose the president, voting by state delegations, with a candidate needing 26 states to win. Republicans currently control 33 House delegations and Democrats 14, with three states split evenly.

The Senate, voting as individuals, would select the vice president. Counting the two independents who caucus with them, Democrats now hold a 53-47 edge in that body.

The constitutional framers set up the system, which the 12th Amendment modified in 1804, in anticipation that the House would frequently, perhaps even usually, make the final selection for president.

Instead, the fallback system hasn’t kicked in since 1824, when Andrew Jackson was the top vote-getter among four candidates in the Electoral College, leading John Quincy Adams, Henry Clay and William Crawford.

In the House, Clay threw his support to Adams, securing his election as the country’s sixth president. Soon thereafter, Adams named Clay to be his secretary of state, an arrangement Jackson condemned as a “corrupt bargain.” Four years later, Jackson won a rematch, ousting Adams.

The potential exists for similar intrigue in 2012.

Obama and Romney could reach a 269-269 deadlock in any of several ways. One possibility is that Obama could win Nevada, Virginia, New Hampshire and Colorado, with Romney taking Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, Iowa and Wisconsin. A second scenario would require Romney to win Florida, North Carolina, Iowa, Colorado, Nevada and Virginia, and Obama to capture Ohio, Wisconsin and New Hampshire.

The possibilities would multiply should either Nebraska or Maine produce a mixed result. Both states award some of their electoral votes by congressional district, eschewing the winner-take-all format used in the other 48 states and the District of Columbia.

“This is going to be an awfully close outcome, so a 269-269 tie is certainly possible but very unlikely,” said Charlie Cook, editor and publisher of the nonpartisan Cook Political Report.

Complicating matters is that the allocation of electors may not be clear for days. A race close enough to produce an Electoral College deadlock would probably mean that the results in at least one state will be close enough for the losing side to contest, Foley says.

That could involve a delay until provisional and absentee ballots are counted, or it could mean a recount, Foley said. A candidate who must win a recount to achieve a tie might face pressure to concede, particularly if he lost the nationwide popular vote, Foley says.

The electors are scheduled to meet in their respective states on Dec. 17 and cast their votes in the Electoral College. The vast majority, and perhaps all, will be party loyalists who will vote for the candidate selected by their state’s voters.

But even that is no guarantee as electors have gone rogue nine times over the past 16 elections, according to Robert Alexander, a political science professor at Ohio Northern University.

Should the 2012 vote produce a 269-269 split, the electors would face “an intense lobbying campaign,” he said. “Can’t you imagine the amount of pressure that would be placed on these human beings to try to resolve the potential Romney-Biden administration before it came to that?”

Only about 30 states bind electors, either through state law or party-enforced pledges, Alexander said.