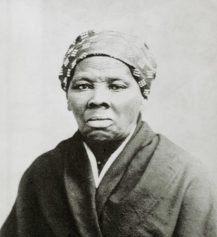

They were once the domain of working class African-Americans, vibrant neighborhoods where the black community looked to its local church for both spiritual and social leadership during times of crisis.

But gentrification and the reversal of white flight have altered the demographics of these same communities, leaving the black church in the precarious position of having to struggle for its very survival, let alone its once-formidable influence.

In cities across America, a new population is moving to neighborhoods formerly occupied by working-class African-Americans. Property developers, eager to take advantage of the modest rent, are tearing down old buildings to make way for trendy eateries and luxury condominiums to fit the needs of millennials: young, educated individuals, most of whom reside briefly in a given urban area before choosing to settle elsewhere.

According to Neil Smith, a professor of anthropology and geography at the City University of New York Graduate Center, gentrification has changed enormously since the ’70s and ’80s.

“It’s no longer just about housing,” he told the New York Times. “It’s really a systematic class-remaking of city neighborhoods. It’s driven by many of the same forces, especially the profitable use of land. But it’s about creating entire environments: employment, recreation, environmental conditions.”

In Brooklyn’s Williamsburg and Greenpoint, for instance, the proportion of residents holding graduate degrees quadrupled to 12 percent from 1990. At the same time, the retail focus has shifted from offering products to creating experiences.

In the nation’s capital, black churches have refused to budge amid this accelerated gentrification process, even as they see their communities and influence slowly wane. For the first time, African-Americans are no longer D.C.’s major racial or ethnic group. Select D.C. neighborhoods are experiencing a verifiable identity crisis, with the black church at the helm.

The changing demographics are a daunting challenge for an institution that used to occupy an integral role in the community – serving as the center of stability and camaraderie, offering potlucks and after-school care along with religious services. The black church was at the forefront of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s that transformed America.

So to understand this struggle is to understand the changing role of the black church in the American narrative, and what vulnerable communities stand to lose if it disappears.

Today, with an electorate still bitterly divided over the issue of race, the black church is arguably losing its power. While “white flight” and the Civil Rights movement galvanized the black community, “black flight” (middle-class African Americans relocating to the suburbs) and the rapid gentrification of neighborhoods across America have put the black church on the path to becoming obsolete.

In Washington, D.C., these demographic shifts have been particularly fraught. Many neighborhoods are recovering even today from the 1968 riots, a four-day response to Dr. King’s assassination. The H St. corridor saw numerous buildings destroyed during the violence. But even as storefronts remained boarded up, churches continued to thrive. Church members in the area look back wistfully at the many events once sponsored by or held at the church, including potlucks, tutoring sessions to help teens stay in school, Alcohol Anonymous meetings, single-parent funds, and counseling services. Pews were packed every Sunday morning, where everybody knew each other by name.

Only in the last few years have these churches felt their bases slipping away.