RIO DE JANEIRO — Wearing full-skirted white dresses and turbans, the religious leaders chanted blessings and sprinkled water on the concrete floor of a modest house near this city’s port. Beneath their feet were the remains of tens of thousands of African slaves who had died shortly after arriving from their horrific sea voyage.

The bodies had been dumped into a fetid, open-air cemetery, often chopped up and mixed with trash. With the 15-minute ceremony this week, the Afro-Brazilian priests were finally giving the slaves at least the semblance of a proper burial centuries later.

“I thank God for this opportunity,” said Edelzuita Lourdes de Santos Oliveira, or Mother Edelzuita, a well-known leader of a house practicing the candomble religion. “We honored our ancestors today with songs left by them.”

It’s been a long journey not just for the slaves but also for the owners of the house and others seeking to recognize the tragic history in a multiracial country that has often avoided its legacy of slavery and racism.

In this case, the remains were discovered by accident, when a couple bought the property in 1996 and started refurbishing it. In the following years, the bones had stayed in pits opened first by construction workers, then researchers. Now, visitors inside the house can look through glass

Glass pyramid covers allow the viewing of remains of African slavespyramids onto exposed ground and the remains of some of the approximately 20,000 men, women and children interred there.

Most of the newcomers were Bantu, part of a broad grouping of ethnicities in south-central Africa. They had one common characteristic: They all believed that without a burial, they would not be able to reunite with their ancestors, according to researcher Julio Cesar Medeiros Pereira, author of a book about the cemetery.

“What I’m feeling now is that these ancestors who for long years were buried here are finally living again,” said Mother Edelzuita.

The cemetery was part of what was once the busiest slave-trading complex in the Americas. Up to a million men and women first stepped onto the New World here and were then held in some 50 warehouses nearby until their sale.

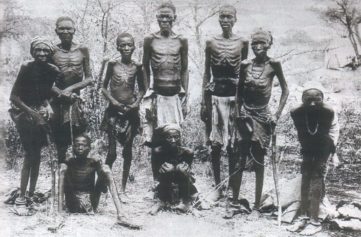

Many of the slaves died before being sold, weakened by the cross-Atlantic trip, and their bodies were buried in what was known as the “cemetery of new blacks,” which operated in Rio between 1769 and 1830, though it was closer to a dump than a cemetery. Bodies of such “new blacks,” called that because they had just arrived, were thrown into mass graves, burned, and their bones chopped up to make room for more…

Read more: Juliana Barbassa, Huffington Post