South African stand-up comedian Trevor Noah

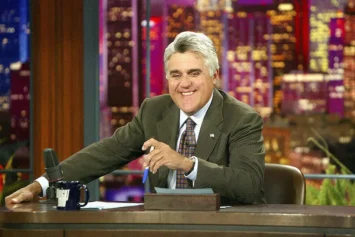

When the young South African comedian Trevor Noah took the stage on The Tonight Show earlier this year to deliver a five-minute set, Jay Leno and guest Glenn Close could be seen roaring in the background, echoing the studio audience that was eating out of Noah’s hand. It was a big moment: for the first time, an African comedian had taken the mic on stand-up comedy’s biggest traditional showcase, and he’d killed. Back home, sub-Saharan newspapers trumpeted Noah’s appearance as if it were breaking news, and MSNBC Africa rebroadcast the show across the continent.

Noah—just 28, handsome, thoughtful, and very funny—is already a huge deal in South Africa. In a few short years, he’s risen from amateur clubs to being a headliner capable of selling out large theaters for his one-man shows. All this, in a nation where stand-up comedy is still a maturing art. Noah’s DVDs are bestsellers, and he’s already had a run as a talk-show host. When a clip of his routine ridiculing South Africa’s abysmal phone service went up on YouTube, the CEO of a local mobile provider took out a full-page ad in Jo’burg’s Sunday Times to apologize to Noah directly—and then hired him as a pitchman.

Not that Noah always sticks to What’s-with-cellphones-these-days? material. His comedy is political, trenchant, delivered in an easy style that probes sensitive subject matter without being overtly confrontational. This is perhaps what’s made him so appealing despite South Africa’s fraught racial landscape, which is often more complicated and rawer than America’s own. “I’m always fascinated by the way we treat race everywhere,” Noah says. “I’ve always seen race from different points of view, just because of my upbringing.”

Noah was born to a black mother and a white father 10 years before apartheid ended. (“I was born a crime,” he said on Leno.) When he was little, his mother walked ahead of him and pretended not to know him if she saw the police (“I felt like a bag of weed,”), while his father, he says, walked on the other side of the street, waving to him “like a creepy pedophile.” Noah’s comedy emerges from his layered outsider status: mixed race—not black nor white nor Indian nor “Coloured” (the official apartheid ethnic category made up of the mixed descendants of the Dutch, British, Malay, Indonesian, and native Africans). The title of Noah’s one-man show, The Daywalker, refers to a fib his family employed to explain his light skin to the rest of his Soweto township: he was albino, but an unusual one—an albino who didn’t have to worry about a sunburn.

South Africa’s tangled social, ethnic, and tribal categories are a rich vein of comedic material. As yet, the nation hasn’t produced a breakout global stand-up star, but Noah’s insights into group mentality make him a strong candidate to be the first comic to make the leap. He speaks five languages and moves seamlessly from impersonating a Russian spy-movie villain to a novice Indian mugger to a Coloured fisherman. He parrots township dwellers, Afrikaner yuppies, and inner-city African-American schoolchildren. A favorite bit has him impersonating President Jacob Zuma as the leader slowly trawls through Facebook, trying to find and friend Barack Obama.

Noah’s expanding cast of characters gives him access to a range of audiences that few other comics can match. But he’s not just a serial impressionist—he’s more a cultural chameleon who has learned to mine his surroundings as much for survival and human connection as for comedy. “I grew up in such a mixed family,” he says. To communicate with his grandparents, or his aunts and uncles, “you’d have to change your voice—you had to speak with a certain accent, otherwise people would not understand one word of what you were saying.”

Indeed, it’s Noah’s fearlessness in tackling the tricky issues of racial identity that makes him so accessible to American viewers. After all, comedy can sometimes seem like the only public space where Americans can speak honestly about their experiences of race and ethnicity—where the likes of Chris Rock, Louis C.K., Dave Chappelle, Wanda Sykes, and Margaret Cho force us to acknowledge biases we may have grown weary of but haven’t resolved. The last section of Noah’s Tonight Show set focused on his fascination, as an African, with African-American speech patterns. Some commentators found the bit hilarious; others found it made them uncomfortable.

Last summer Noah moved to Southern California. “I’ve always wanted to be a comedian in the world,” Noah says. “I don’t want to be labeled a South African comedian.” Yet as another South African comedian, John Vlismas, pointed out, while Noah’s rapid ascent has provoked some resentment among a few of his peers, Noah’s turn on Leno and his attempt to make it in America are “such a big deal for all of us—for South African comedy. In fact, it could even create a new image in American minds about the level of sophistication South Africans have in general.”

In the meantime, Noah has been honing his craft on the road, putting in the miles and gathering new material for a Comedy Central special and a big live show produced by Eddie Izzard. Not surprisingly the realities of race in the U.S. have made a deep impression on him. “We have a very common history,” he says. “I very immediately understand a lot of things happening out here. It’s very similar to back home—there’s still the black club, the white club, the Latino club, the black restaurant.”

Touring with Latino comedian Gabriel Iglesias has also been instructive for Noah. “I’ve performed to people in hunting jackets in the middle of the South that are coming to his shows. He shows me that it doesn’t really matter what you look like or where you come from; funny is funny. You can find your audience regardless of who they are, and who you are.”

Source: Newsweek