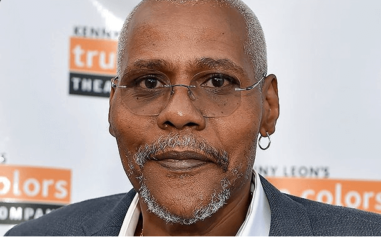

Most actors create one or two memorable characters in a career, if they’re lucky. The portraits etched by the mercurial Giancarlo Esposito, on the other hand, are so distinct that you can imagine them playing scenes off each other.

It’s tantalizing, for instance, to imagine Buggin Out, the Brooklyn gadfly who led a pizzeria boycott in Spike Lee’s film “Do the Right Thing” (1989), stopping for fried chicken at Los Pollos Hermanos and having some choice words with the chain’s owner, Gustavo Fring, the buttoned-up criminal mastermind who sent an electrifying chill through recent seasons of “Breaking Bad” on AMC.

You could go on for a while like this, given a career that spans 47 years (he began recording radio commercials at 7), every conceivable medium, and roles on both sides of the law and myriad points on the racial spectrum.

“I have been called a chameleon, and I rather like that, because it means that the things I choose are never the same,” Mr. Esposito said recently over lunch in a tiny Bronx diner. “I don’t want to play myself over and over again.”

But wouldn’t it be nice to play himself at least once? He may be closer than usual with Donaldo Calderon, the fictional Bronx borough president in “Storefront Church,” a new play written and directed by John Patrick Shanley at the Atlantic Theater. (Now in previews, the play, the third in a trilogy that includes “Doubt” and “Defiance,” opens on June 11.) Like Calderon, Mr. Esposito, 54, grew up, at least partly, in the Bronx; and like the half-Italian, half-Puerto Rican Calderon he’s multiethnic, the child of an African-American opera singer and an Italian carpenter she met and married while on a European tour.

The play’s central conflict, a battle between a bank and the owners of a defaulting property that includes the Pentecostal church of the title, also rings a few bells.

“The play is resounding for me in that in the last economic downturn I had a house that went into foreclosure,” said Mr. Esposito, who lives in Ridgefield, Conn. “And my mother, after being an opera singer, became a minister and had a little storefront church in our home in Elmsford, N.Y. She called it a Place of Light Continuing. I think Shanley must have channeled my life, or my life must be very much like his.”

Whatever the biographical convergences that Mr. Esposito shares with the Bronx-bred Mr. Shanley, in rehearsal they’re in different orbits, the playwright said recently.

“I’m not sure I’ve ever worked with any one exactly like him,” Mr. Shanley said. “He’s like a priest. He comes in in a suit, he has a separate table, he works alone through every break. He’s off in his own little rectory. He’s very convivial once you engage him, but the guilt quotient is high.” Others in the company feel foolish “next to that,” he added.

Mr. Esposito did consider the priesthood before the acting bug bit, and even today his talk turns easily to matters of spirituality and identity. Raised as much in the Catholic as the Pentecostal church, he was friendly mostly with Jewish kids in high school because, he explained, neither the Italian-Americans nor the black students accepted him. He brings so much to his acting because he seeks so much from it.

“It was a long journey to find myself,” said Mr. Esposito, whose earnest, meditative streak is leavened by a deep, disarming laugh. “Partly that journey has been to seek out characters where I could just be human and didn’t have to represent a color, so that I could strengthen that in myself, so I didn’t have to fall into taking sides.”

A turning point came in 1980, when he was cast in the title role of Charles Fuller’s “Zooman and the Sign”at Negro Ensemble Company. Mr. Esposito, then 22, played a sociopathic street thug, a role he researched, he said, by hanging out with “ne’er-do-well young bucks” in Philadelphia, where the play is set.

Similar roles as violent heavies inevitably followed, but so did an escape route from the trap of stereotype. A young Spike Lee was among those who saw “Zooman.”

“I came to a wonderful understanding through working with Spike on those movies and disagreeing with him about race,” said Mr. Esposito, who has been in five of Mr. Lee’s films. “He was completely pro-black and anti-white, and I didn’t feel that way in my heart. I felt like I wanted to be a human being and represent myself as such, but every time you walk out into the world, you’re treated a certain way.”

The black-vs.-Italian contretemps of “Do the Right Thing” hit particularly close to home, he said.

“I remember wanting my father desperately to see that movie, so maybe he’d understand what my walk in life was,” Mr. Esposito said. “He regarded me, obviously, as his son, this little Italian boy with dark skin, but I don’t know if he ever really understood what I dealt with in the world. And that is that this skin is inescapable.”

Acting might not have provided an escape, exactly, but Mr. Esposito said it helped him “transcend.”

Now, even when he plays villains — the tightly coiled Gus Fring, say, or Captain Neville, a hard-nosed militia leader in “Revolution,” a new J. J. Abrams series having its debut on NBC in the fall — he comes to the roles on his own idiosyncratic terms.

To read entire story by Reb Weinert-Kendt, go to NY Times