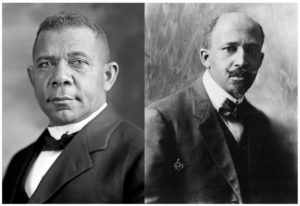

Conversations regarding Black Conservatism tend to revolve around if the Black community should focus on economic equality — as championed by Booker T. Washington (left) — or on social justice, as proposed by W.E.B. Du Bois (right). (Courtesy: WikiMedia)

During a campaign stop in 2016, the nation winced when Donald Trump pointed out the sole noticeable African-American in the audience. “Oh, look at my African-American over there. Look at him. Are you the greatest?” Trump said without being noticeably aware of how condescending he sounded.

Over the two terms of President Obama, Trump directed opposition campaign against Obama that centered on whether Obama was actually born in Hawaii. These claims, which basically alleged that Obama was not an American at all, were perceived to be racially motivated. Trump, who first faced public accusations of racial bias at least as early as a 1973 Justice Department housing discrimination lawsuit, did nothing to dispel these claims with his response to the Charlottesville protest and his resistance to denouncing white nationalists. Despite this, some African-Americans have been found supporting Trump, to the astonishment and confusion of the larger Black community.

Trump managed to secure more of a percentage of Black votes in 2016 than any other Republican in a presidential election since 2004. While this pales to Dwight Eisenhower — the last Republican to receive more than 25 percent of the Black vote in a presidential campaign and is a far cry from Trump’s claim of being able to gain 95 percent of the Black vote in 2020, reveals cracks in the otherwise politically monolithic façade of the Black community.

African-Americans are overwhelmingly Democratic. The most politically homogeneous socioeconomic group in America, African-Americans have grown to become a key and critically vital stakeholder in the Democratic Party. Despite this, only 47 percent of African-American voters identify as being liberal. As of 2012, where the Black vote secured President Obama’s second term, 45 percent of African American voters identified as conservatives.

The feelings from the Black community toward Black conservatism tend to be best expressed by the Rev. William Barber II’s objection to South Carolina’s Senator Tim Scott (R). Barber was the president of the North Carolina NAACP at the time: “A ventriloquist can always find a good dummy. The extreme right wing down here [in South Carolina] finds a black guy to be senator and claims he’s the first black senator since Reconstruction, and then he goes to Washington, D.C., and articulates the agenda of the Tea Party.”

Despite this, there is the feeling that the Democratic Party has grown to be the perceived “party of last resort” for African-Americans due to the Republicans’ rejection of African-American concerns and — in some notable cases — African-Americans themselves. Increasingly, there is an ideological difference between the portion of the Black community that sympathizes with conservative philosophies versus the part that sees itself as progressive. It is in this schism that the future of the Black community’s political identity lies.

Salvation by God’s Hands

What exactly is Black conservatism? To begin, it should be noted that, in most cases, it is not the same as white conservatism. From a historical point of view, Black conservatism comes from two veins, one of these being the Black church. A 2004 survey found that among religious groups Black Protestants are one of the most socially socially conservative groups in America, second only to white evangelists.

Those belonging to this vein believe that empowerment can and will be divinely delivered. This is in contrast to waiting for or pushing for rectification and acknowledgment of past and current grievances.

Empowerment, or the power to change one’s fate by one’s own device, is a key element in Black conservatism. Reflective of the philosophy of Frederick Douglass, it argues that one cannot escape one’s current reality without making oneself better.

“I have often been so pinched with hunger, that I have fought with the dog — ‘Old Nep’ — for the smallest crumbs that fell from the kitchen table, and have been glad when I won a single crumb in the combat,” Douglass wrote in “My Bondage and My Freedom.” Douglass argued that while hunger was always an ever-present reality, worst were the master’s gestures of generosity, such as insistencies on becoming drunk during Christmas. This, per Douglass, raised the specter of being free men, only to be confronted with slavery afterward. “Many times have I followed, with eager step, the waiting-girl when she went out to shake the tablecloth, to get the crumbs and small bones flung out for the cats.”

For Douglass, the ability to escape his fate did not come until he learned the alphabet and became literate. Douglass believed that education more than anything else could free African-Americans. By giving them the keys to their own salvation, Douglass thought that Blacks could be agents for their own empowerment, without the leniency or blessings of those that would imprison them.

It would follow, accordingly, that African-Americans that relate closely to the church and to the Bible would feel that the “road to a better life” is only possible through God. These African-Americans would more likely identify with conservative philosophy, which tends to correspond more closely with theological teachings.

“Conservatism is also about conserving the best of the past,” Lee H. Walker, president of the New Coalition for Economic and Social Change, wrote. “Conservative blacks are committed to this as well. The oldest and still most important conservative institution in black America is the church. That is where much of our leadership came from and many of the first schools open to blacks, and many fine schools serving black students across the country today. In many black communities, churches serve as engines of economic development, too.”

“Discussing the similarities and differences between white and black conservatism is similar to discussing how black and white Christians differ. They may belong to the same denomination and even the same church, but when they attend church on Sunday mornings, the service and the experiences may be very different.”

The Booker T. Washington Argument

Conservative ideology stresses the importance of that empowerment can be developed personally. This philosophy is a descendant of Booker T. Washington’s 1895 Atlanta Exposition address, which called for Southern whites to guarantee basic education and due process under the law for African-Americans and for Northern whites to support Black education in exchange for submission to white rule by Southern Blacks.

While rejected by other Black community leaders, like W.E.B. Du Bois, Washington’s argument that economic power is more important to personal empowerment than political power persisted. The argument held that with enough economic influence or, as Washington put it, “industry, thrift, intelligence, and property” the Black community can successfully force political recognition from white politicians.

Black conservatism plays to many of the defining themes of White conservatism: traditionalism, capitalism, faith in the free markets, social conservatism, and strong nationalistic identity. A key difference, however, is that Black conservatives typically adhere to Washington’s philosophy by arguing that personal empowerment through education and professional success and the promotion of safety and security in the Black community are more important than embracing victimization of societal racism. The belief that “the welfare state,” or the belief that a government can play a primary role in social advancement is eschewed for the idea that personal responsibility for the social and economic well-being is individually obtained. Conservatives believe that Black people have been duped into a state of laxity, waiting for the ‘state’ apparatus to help us.

In addition, common among Black conservatives is the notion that protesting or challenging the historical or current state of race relations between whites and Blacks — including calls for affirmative action and protests from groups like Black Lives Matter — is pointless and a waste of energy in a predominately white nation. Such energies are better used toward personal development, per Black conservatism.

“The government is not your salvation. The government is not your road to prosperity,” Mia Love, who in 2012 became the first African-American Republican woman to run for a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives, said. “Hard work, education will take you far beyond what any government program can ever promise.”

A People with Nowhere to Go

Another question that must be answered is “Why is the Black community so loyally Democratic?” To begin with, following the Civil War, African-Americans were not loyally Democratic, but loyally Republican. At the time, the Republicans were the liberal party, and Republican presidents — particularly, Ulysses S. Grant — sought to strengthen the protections of African-Americans in the South and promoting Reconstruction efforts. Through Grant, for example, the Ku Klux Klan was nearly wiped out; the group was only able to regain national prominence in the 1920s. The abolitionist movement was largely Republican-driven.

Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, which pumped federal money into historical minority communities, helped to break the Republicans’ iron grip on the Black community. The New Deal Coalition — which dominated presidential elections from the 1930s to Lyndon Johnson in the mid-1960s, with the singular exception of pro-New Deal Republican Dwight Eisenhower — was the first voting coalition to center around African-Americans.

Herbert Hoover’s move to fire African-Americans from party and government positions in order to curry favor with white voters soured relations between Blacks and Republicans even further. What finally pushed the remainder of the Black community from the Republican Party, however, was what is now known as “the Southern Strategy,” which was an aggressive appealing to Southern whites’ racial resentments and animosities to win their support from the Democratic Party. With the Northern Democrats supporting the Civil Rights movement, the Republicans embraced the backlash of the political realignment of the South, defended suburbanization as de facto segregation, and painted the narrative that Whites were under threat from Black advancement and Black criminality.

This locked up the white vote in the South for the Republicans for more than a generation. This also drove the Black vote to the Democrats, who historically were political opponents to the Black community.

The Black vote has become an essential and reliable part of the modern Democratic voting bloc. However, this is a vote the Democratic Party does not have to work for, as the alternative is to vote Republican — where some of the party’s platform planks directly and indirectly are adverse to African Americans and where some party members openly show racial animus. This advances the perception that the Democrats take the Black community for granted and do not work as hard to promote African-American interests as they do for other members of the voting bloc.

Trump as an Alternative

Christina Greer is an associate professor of political science at Fordham University. She said that the electoral support Trump enjoyed from Black voters is not indicative of any shift in Black voting loyalty, but an indication of voter fatigue and a need for something new.

“There are many voters out there — not just African-Americans — that feel that the parties are not serving their needs. However, when you look at African-Americans, who tend to vote so loyally Democrat, those that vote against the flow tend to get noticed and tend to draw questions about why they would knowingly vote against their own interest,” Greer said.

“When you have but just two parties, when there are not more parties effectively in play to satisfy one’s political angle, strategy comes into play. African-American voters are the most strategic voters because they have the most to lose. The calculus that goes on to consider one’s vote tends to be intricate and by no means arbitrary in the Black community. It tends to be weighted towards considering if one can get what he needs from a particular candidate.”

Greer pointed out that nationally Republican politicians tend to paint with broad, stereotypical strokes that demonize or denigrate the Black community. On a local or state level, however, Republican politicians have more space and freedom to address the issues without racial overtones. This helps to explain Chris Christie’s 2013 election win, where he won 20 percent of the Black vote in heavily Democratic New Jersey, where Mitt Romney barely got four percent one year prior in the 2012 presidential election.

There is the sense among some Blacks that Trump, a former Democratic backer-turned-third party supporter-turned-Republican candidate, represents such a departure from what has been generally accepted by the political parties that — along with his pro-business, pro-domestic growth economic agenda — he was worth taking a shot on, despite his personal failings. The feeling that President Obama failed in his promises to promote and champion Black interests is a factor as well.

“I’m tired of hearing about the dream,” Fabian Williams, a 41-year-old artist from Atlanta, said to the Los Angeles Times. “I’m over poetic sentiment. It sounds good, but the country has been stuck in the same position for 40 years.”

“You can’t be black when you’re a candidate,” Michael Steele, the former lieutenant governor of Maryland and former chairman of the Republican National Committee, said. “We’ve seen this play out with Barack Obama. I think he’s taken the short way out, which is not to deal with the issue of race at all effectively, except for when he really has to. He can’t be seen talking about black issues because all of the sudden, now it’s ‘Oh my God, then all you care about are black people.’ … But then again, if you don’t say enough, then you have black folks pissed off at you.”

A larger concern is a lack of engagement. If Black voters fail to report to the polls, any political power the Black community may have would be lost. The question of if African-Americans are indeed a politically captive group — where not only its vote is anticipated, it is expected despite candidates issuing policies directly in opposition to Black interests, such as Bill Clinton with his welfare and 1994 crime bills — may be better phrased as what exactly is keeping the Black community so loyal?

“Democrats are unequivocally better than the Republicans on a whole range of issues that a majority of Black Americans care about,” Princeton political scientist Paul Frymer told FiveThirtyEight. “This is why they are captured. The Democratic Party, by doing more than nothing, is better than the Republican Party. The vote is always clearly differentiated and yet at the same time, marginalized.”

“There are other groups that vote heavily Democratic — Jewish voters, for instance — that are not ignored by either party. Both parties make strong appeals to Jewish voters with regards to Israel, for instance, without fear of destabilizing their broader coalition,” Frymer added, noting that only with Black voters is there a fear that addressing their needs will turn away other voters.