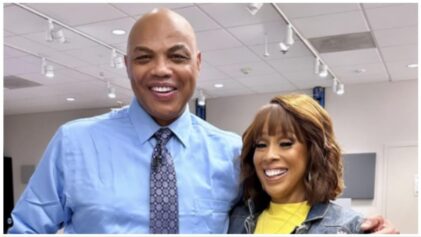

Basketball star Charles Barkley hosts a new TNT series on racism.

Gil Scott-Heron was wrong.

In 2017, you can binge watch the revolution on Netflix.

During a May NPR interview with the stars of ABC’s beloved sitcom “black-ish,” the current Hollywood era was described as “a renaissance of shows featuring, written or produced by people of color.” Beyond spotlighting Black dramatists and filmmakers, countless new series are centrally focused on racism and its erosion of Black life. Conscious content makers hope substantive viewing educates and resonates with the Black Lives Matter generation.

Standup comedian W. Kamau Bell and retired basketball star Charles Barkley both launched prime time series that address dire issues such as police terrorism against Black citizens and the rise of white nationalist politicians like Richard Spencer of “alt-right.” But Bell and Barkley are television personalities, not trained race theorists. After reviewing both shows, Journalist and National Public Radio’s first full-time TV critic Eric Deggans confesses disappointment that both projects spliced gripping subject matter with “jokey asides” but failed to ask “tough, detailed, direct questions.”

The Netflix series “Dear White People” the television series based on Justin Simien’s 2014 independent film was similarly disappointing according to Journalist professor Jason Johnson. He described the 10-episode series as a “comedy that is steeped in the politics of Black life and pain” but unwilling to risk indicting white viewers for being complicit in the dramatized and real-world violence against Black people.

Kenya Burris, the creator of “black-ish,” told NPR that he uses his sitcom to talk “about those things that make us uncomfortable.” Despite relying on an audience that’s 75-percent white, Barris infuses episodes with protests against police shootings, homages to minister Malcolm X and cameos for the 2015 book, “Between the World and Me” and its author, Ta-Nehisi Coates.

It’s easy to assume Barris being employed to produce three seasons of such content represents a modicum of progress and an indicator that many white viewers are receptive to Black perspectives on racism. Unfortunately, that’s not necessarily the case.

There’s a robust record of whites adhering to racist convictions while consuming narratives of Black pain. The late historian Vincent Woodard’s book, “The Delectable Negro,” details 19th-century whites who devoured Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin,” a novel celebrated for and credited with detailing the horrors of Black enslavement and igniting the Civil War. However, Woodard documents that, for some readers, the thought “that one man could possess, sell or whip another, caused … intense excitement.” Stowe’s “romanticized images of slaves” and depictions of Black suffering satisfy a peculiar taste acquired from centuries of dehumanizing Black people.

Professor Amy Louise Wood corroborates Woodard’s analysis with her research on the history of Black mutilation as a form of entertainment. In “Lynching and Spectacle: Witnessing Racial Violence in America, 1890-1940,” she explores decades of lynchings and examines how these public mob killings became productions of racist theater. Emphasizing that lynchings were often advertised in advanced for maximum audience attendance and participation, Wood writes that these “rituals … and their subsequent representations imparted powerful messages to whites about their own supposed racial dominance and superiority. These spectacles produced and disseminated images of white power and Black degradation, of white unity and Black criminality, that served to instill and perpetuate a sense of racial supremacy in their white spectators.” Whites affirmed their racial identity and dominion over Black people by witnessing staged slaughters.

In a 2016 interview, Woods acknowledged similar messages of racial dominance are transmitted when footage depicts the final moments of Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Eric Garner or the most recent victim of the white supremacy police state. Dash cam and cellphone footage captured with hopes of safeguarding citizens’ rights and guaranteeing accountability for police misconduct often become widely viewed confirmation of Black subjugation.

Journalist and author Isabelle Wilkerson also detected a symmetry between antique photos of Black people being hung and the now endless loops of police violence “caught on videotape [that] have reached hundreds of thousands of watchers on YouTube — a form of public witness to brutality beyond anything possible in the age of lynching.”

Even with a virtual crowd, the multitude of onlookers is often insufficient to criminally convict modern-day lynchers.

This viral and vicarious feast on Black suffering suggests a large population of whites have no problem digesting, and perhaps even crave, content that confirms the continued abuse and exploitation of Black people. The enormous social media presence of Black Lives Matter protesters appeals to unscrupulous advertisers willing to use the name of Tamir Rice to hawk toy pistols.

Pepsi’s recent public relations miscalculation demonstrates the shameless commodification of Black life and the years of political protest against white supremacy. The soft drink giant released a commercial depicting a fictionalized rally and the requisite phalanx of enforcement officials. A carbonated beverage establishes racial harmony where years of grassroots activism proved fruitless.

The tacky affair supports Johnson’s critique that, “So long as you can sell it to white audiences,” counterfeit concern for Black issues may be a profitable shtick for peddling merchandise or television shows.

Television star and filmmaker Jordan Peele told The New York Times he crafted the breakout horror flick “Get Out” to confront “the lack of acknowledgment that racism exists.” He deconstructed the symbolic meaning of television in the movie, describing it as a marker for inaction and escapism, similar to “the fact that the entertainment industry is not necessarily inclusive of the African-American experience,” Peele said.

That lens should frame our reception of and response to the sudden marathon of racially focused viewing options.

—————————————————————————————————

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.