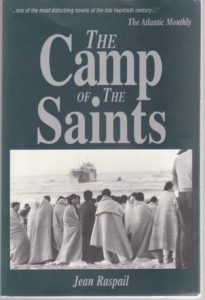

President Trump supporters have suggested Jean Raspail’s 1973 French novel, “The Camp of the Saints.”

During Barack Obama’s tenure as president, he and Michelle Obama recommended a number of books to reveal truth about racism. They cited iconic works like W. E. B. DuBois’ “The Souls of Black Folks” and Ralph Ellison’s “Invisible Man,” as well as contemporary gems like Isabel Wilkerson’s “The Warmth of Other Suns,” which chronicles generations of Black citizens fleeing racial terrorism in the southern United States. The Obamas recognize the immense influence books have on a person’s thoughts and behavior. The prestige of the Oval Office amplified their ability to showcase literature that best represents their values and political leanings.

President Donald J. Trump’s administration and his Republican allies have a different syllabus. Chief White House strategist and Breitbart News founding board member Steve Bannon and Republican Congressman Steve King have each publicly recommended the 1973 dystopian French novel “The Camp of the Saints.” A Huffington Post review brands Jean Raspail’s fictional narrative “nothing less than a call to arms for the white Christian West, to revive the spirit of the Crusades and steel itself for bloody conflict against the poor Black and brown world.” Like Pierre Boulle’s 1963 “Planet of the Apes,” “The Camp of the Saints” was originally published in French. Raspail flawlessly imports racial stereotypes about shiftless brutal and “sexually” dangerous Black males. The book’s anti-Black, anti-immigrant sentiment mimics the 2016 campaign rhetoric that netted Trump the presidency.

Bannon served as chief executive director of Trumps campaign and repeatedly invokes Raspail’s fiction when articulating what the Los Angeles Times calls, “a dark view of refugee and immigration flows from majority-Muslim [non-white] countries.” Trump’s chief strategist is a primary architect of the immigration ban on people from predominantly Muslim nations. In January of 2016, Bannon justified the need for the draconian restrictions, declaring that non-white Muslims are not “migrating” to the United States. From Bannon’s perspective, “It’s really an invasion. I call it the ‘Camp of the Saints.'”

Congressman King mirrors Bannon’s talking points, promoting what Atlanta Black Star Political Editor Kamau Franklin classifies as “the centralization of whiteness to politics.” Earlier this month, Talk radio host Jan Mickelson asked Congressman King, the Iowa Republican about the threat posed to white civilization in the form of “whatever washes up on our shore and makes a claim on our territory.” Representative King replied by spelling Raspail’s whole name while recommending the Frenchman’s work.

University of Texas Austin English professor Martin Kevorkian rejects trivializing the suggested reading of powerful white men and white men who feel powerless and cautions against minimizing Raspail’s work as a distasteful oddity.

“That idea of a non-white threat to whites is extremely common” in United States literature, Kevorkian said. He reminds us that racist themes in “The Camp of the Saints” are identical to one of the most significant novels in United States history, Thomas Dixon’s 1905 “The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan.” The book, which became the basis for D. W. Griffith’s 1915 landmark film “The Birth of a Nation” which was screened at the White House, resurrected the Ku Klux Klan as the protectors of white society and white female virtue against Black “incompetence” and lustful desire of white women.

Literature like “The Clansmen” and “The Camp of the Saints” simultaneously inspires white angst and white violence against anyone not white. The story lines invariably depict a time when whites fail to maintain power over Black people. These “scary stories” motivate racists to remain committed to the preservation of collective white power, which often necessitates force. Dark people are relentlessly depicted as subhuman monstrosities capable of one thing: soiling white rule.

“The Turner Diaries,” published in 1978 by William Luther Pierce and described by the New York Times as “a classic among white supremacists,” is indistinguishable from the recommended reading of King and Bannon. Pierce imagines a world where white domination is in decline, evidenced by gun prohibition and the nagging pestilence of Black males attacking white women. Timothy McVeigh, the Oklahoma City bomber read “The Turner Diaries” before bombing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, Okla., and killing 168 people in 1995. The novel includes a scene where a government building is bombed. The New York Times reports that one of the items recovered from his vehicle at the time of his arrest was “a clipping from the novel, which prosecutors have described as a blueprint for the bombing of the federal building.”

Tariq Nasheed, creator of the Hidden Colors documentary series, encourages Black people to review King and Bannon’s reading material.

“It’s imperative that Black people read and study these books that white supremacists keep putting out,” Nasheed said. Classifying “The Camp of the Saints” and “The Turner Diaries” as assaults on Black people, he stressed that racists “weaponize everything, including so-called ‘fictional’ novels.’” As opposed to dismissing these texts as racially insensitive but harmless, we should view these works as public transcripts of white supremacy culture and strategy.

Raspail writes, “A disturbing trend in our present moment is seeing blatantly [white] supremacist material treated in a positive light,” Kevorkian notes. When anti-Black literature is acclaimed from the loftiest corridors of white power, Black life is threatened and aggressively devalued.

—————————————————————————————————

Gus T. Renegade hosts “The Context of White Supremacy” radio program, a platform designed to dissect and counter racism. For nearly a decade, he has interviewed and studied authors, filmmakers and scholars from around the globe.