In the United States, home ownership has been governed by racist institutional practices and policies for years, as more people are acknowledging these days.

In an opinion piece in the Washington Post, David M. P. Freund, associate professor of history at the University of Maryland at College Park, reminded us that housing segregation in the cities and suburbs is not solely the result of individual preferences. Rather, Fruend–author of “Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America” and “The Modern American Metropolis: A Documentary Reader”—noted that rarely have Americans’ decisions about where to live been guided by individual consumers. And yet, this fallacy continues to dominate the national conscience. The author suggests that part of the problem is the celebration of the so-called “free market” of home ownership, despite the fact that the U.S. housing market never was completely free. Racism, after all, is not merely about lynch mobs, racist sheriffs and restrictive covenants forbidding sale to Blacks, but also institutions and governmental policies.

For much of the previous century, racial discrimination guided every facet of this nation’s cities and suburbs. ”Discrimination was sanctioned and aggressively promoted by real estate boards, neighborhood associations, municipal governments, state and federal courts, mortgage lenders, and a host of federal housing and development programs,” the author wrote. “Together they helped to draw sharp neighborhood boundaries, deny equal access to markets and places, and produce obscene disparities in wealth, opportunity and basic quality of life.”

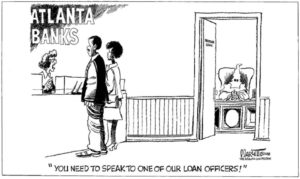

Mortgage lenders, real estate agents and public officials promoted these racist practices, which included redlining, the practice of financial services to certain communities based on race; blockbusting, the practice of encouraging white home owners to sell their houses cheap in order to trigger white flight and an influx of Black people; and official policies to exclude certain groups of people from certain areas in order to keep property values high.

Further, an editorial in The New York Times recently bemoaned the return of the racist practice of contracts for deed. Since Black home buyers were ineligible for federal mortgage insurance between the 1930s and the 1960s, this encouraged their exploitation by scam artists who sold contract for deed, a promise by a seller to hand over a deed after 20 to 40 years of monthly payments. These high interest loans allowed sellers to milk buyers dry, and people were unable to build up equity and were often evicted and ruined. The practice is similar to the predatory and discriminatory subprime mortgage lending that targeted Black home buyers and wiped out their wealth during the Great Recession.

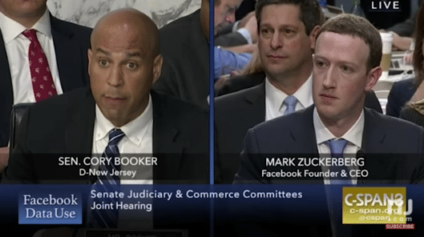

The economics of home buying, lending and development cannot be divorced from the racism of it all—in a nation whose wealth was created by the buying and selling of Black bodies. After all, Wall Street itself was built by enslaved Africans, was the site of a slave market and became a center of global finance because of slavery. And yet, these facts are forgotten. For example, presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, who has championed the cause of wealth inequality and fighting Wall Street excess, has been cited for failing to address the role of institutional racism. For example, the Huffington Post called out the candidate for not mentioning the role of racialized policies including redlining and urban renewal projects in bringing about the decline of cities such as Detroit. In addition, as Rolling Stone recently mentioned, Sanders missed an opportunity to challenge his rival Hillary Clinton’s suggestion that breaking up the big banks would not end racism. “If we broke up the big banks tomorrow,” Clinton asked, “would that end racism?”

Wall Street corruption is not merely a class issue, but a race issue, and the continued use of subprime “ghetto” loans and other tools by vulture capitalists to feed on Black people is proof of it.