Over the past nine years, poverty among America’s public school students has increased a great deal.

According to a report by The Huffington Post, in 2006, 31 percent of students in the U.S. attended schools in “high-poverty” districts, in which at least 20 percent of the students lived below the federal poverty line. Meanwhile, by 2013, the number soared to more than 49 percent, based on U.S. census data analyzed by the nonprofit organization EdBuild, which advocates for more equitable funding for public schools.

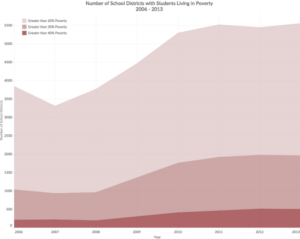

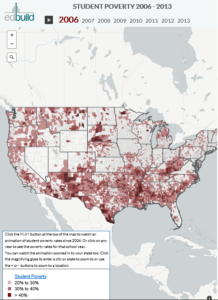

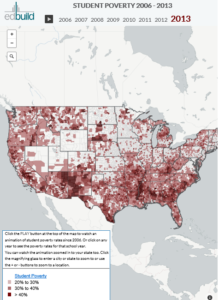

An interactive map produced by EdBuild demonstrates how poverty has jumped over the years. According to EdBuild, the number of kids attending school in these high-poverty communities increased from 15.9 million to 24 million—a 60 percent rise. Meanwhile, students in districts with concentrated poverty—in which at least 40 percent of children live in poverty— jumped 260 percent.

The big takeaway is that in the richest nation in the world, almost half of children between 5 and 17 attend school in communities where a substantial portion of families are struggling to make it, or not managing to keep their heads above water. In such districts, poverty becomes transferable to the next generation, meaning young people are fated to live in a lower economic existence.

Students in poverty need more resources in order to succeed and are more likely to face physical and mental health challenges, yet, as EDBuild points out, states often shortchange these children through regressive school funding formulas.

Looking beyond the national landscape of poverty and delving a little into the data on Black children, it is no wonder that when America has the sniffles, Black America develops pneumonia. As the most vulnerable demographic group in the U.S., African Americans, particularly in this case African American children, suffer from a level of poverty that should cause great concern.

According to a report by Pew Research Center, Black children were roughly four times as likely to live in poverty as white children, and more likely to be impoverished than any other race or ethnicity. While the portion of children in poverty fell from 22 percent in 2010 to 20 percent in 2013, and declined for Latino, Asian and white children, it remained steady for Black children. That year, Black childhood poverty stood at 38.3 percent, as opposed to 10.7 percent for white children, 30.4 percent for Hispanic children and 10.1 percent for Asian children.

Moreover, for the first time in history, the number of poor Black children (4.2 million) has surpassed the number of poor white children (4.1 million) in America—although Blacks only make up roughly 13 percent of the U.S. population. In addition, while Black children are most likely to live in poverty, there are more impoverished Hispanic children at 5.4 million.

The data points to the intractable and ubiquitous nature of Black poverty, in a nation where institutional racism persists, and the unemployment rate for Blacks has remained roughly double the white jobless rate for decades. As usual, Black people are the canary in the coal mine, an indicator of pervasive problems coming to greater society.

If America ignores the problem of children in poverty, it does so at its own peril. And if Black America does not address the issue then its future hangs in the balance.