By Tess Raser

This profile is part of an ongoing series of narratives focused on men and women who have been killed by the police. It is an attempt to counteract media bias, which often vilifies these men, women, boys and girls. These stories have been captured through the voices of the victims’ family members. I have been fortunate to meet the families through my activism in the Black Lives Matter movement and through work in various organizations.

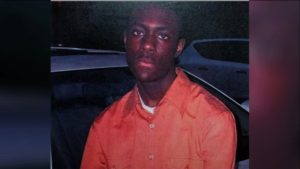

Ramarley Graham was shot dead in his own bathroom on Feb. 2, 2012. He was only 18 years old, and he was unarmed.

Constance Malcolm, Ramarley’s mother, has been fighting for justice for Ramarley for over two years. The city of New York recently agreed to a settlement with Constance, but she will not stop fighting until her son, who was always happy, receives real justice.

Ramarley was one of three siblings — he had an older sister and a younger brother. “He was very happy. He loved to play in the snow when he was younger [with his siblings],” Constance says. She fondly remembers Ramarley and his sister dressing in matching clothes. She giggles about this.

Ramarley was not into rough sports and was not aggressive. “He was more the kid who would just watch the History Channel and Animal Planet channel. He played video games with his brother. He was normal,” Constance explains.

Ramarley’s teachers were fond of him, and he always wanted to help them. Some of his teachers will still come out to rally for justice with Constance. Ramarley was not able to finish school, but he had been applying for jobs to work with animals.

“He would always look at the animals. He liked fish. He had a tank when he was little, and he would take care of his fish. He would take care of them,” Constance says. Ramarley was a normal kid in the sense that he was nonthreatening, kept to himself and, like a lot of young boys, had hobbies and interests that he pursued.

“He was just friendly and helpful, he always wanted to help. He would take his little brother to the park, help him with homework. He helped the old people carry groceries. Everybody knew him from the building,” Constance recalls.

Constance immigrated to the United States from Jamaica when she was young and lived in the Bronx. She remembers that there had always been violence and harassment by the police in her neighborhood, but she was not scared of them.

“The stuff they would do would be concerning to me,” she says. “I have lived in [the Bronx] for 13 and a half years, but I was only living in this apartment for three and a half months,” Constance says of the apartment in which Ramarley was murdered.

On the day of Ramarley’s death, Constance left early to go to work as she does daily. Ramarley was wrapped in a pink blanket and was asleep. This was the last time she would see him alive.

“That day, I left work at 3 p.m., but about 3:15 p.m., I got a phone call from the tenants who live on the first floor who asked me, ‘Are you home?’” Constance explains, “They told me, ‘hurry up and come.’”

This did not sit well with Constance so she headed home. Her neighbor then called her back and was calm but urged Constance to come home. “By then Ramarley got shot, but he didn’t want to tell me,” Constance remembers.

Constance finally reached the block and saw a lot of police. She did not know many people in the community yet, as she had just moved there. “I gave my ID [to the police] and said I live in this house, and the police said hold on. The cops came back and forth. Finally a white shirt came and said to me, can I go to the precinct. I said sure because still nobody told me anything,” Constance says.

Constance’s mother lives with her and was taking care of Ramarley and his 6-year-old brother that afternoon. Constance went to the precinct, and when she got there, the police officers told her to sit and wait. She then heard that officer walk over to the counter and said he was from homicide.

“A couple of minutes later they brought in my mom, and she said they killed Ramarley,” Constance says. They would not let Constance speak with her mother, as her mother did not have an attorney. Constance’s mother was then taken away and questioned and bullied. It’s hard to fully understand the inhumanity in this situation — a mother was sent away from her home, to the police precinct, and not given any information. Her mother then tells her that her teenage son has just been killed and is then unable to give anymore information.

“I started banging on the doors that I saw, and finally when the door opened, I saw [my mother], and they were blocking her so she couldn’t get out. I tried to grab her jacket and get her out. The officer then assaulted me, pushed me to the ground,” Constance explains.

Defeated, Constance had to leave. The police would not let Ramarley’s grandmother leave the precinct. They were determined to bully and intimidate her into changing her story, into changing what she actually she saw, which was Ramarley being followed into his home without a warrant and shot in his bathroom in front of his 6-year-old brother, Chinnor.

“When I left the precinct, they kept [my mother] there for seven hours. The police were just laughing. After seven hours, they finally let her out after trying to put words in her mouth. They were basically trying to put words in her mouth,” Constance says.

Constance headed home to find her younger son. “They removed the barricade from White Plains Road. I showed them my ID, and I said I’m trying to find my son,” Constance says. Finally, one of the police brought her son to her. He only had his underwear and T-shirt on. Chinnor was terrified after watching a police officer shoot his brother dead.

“You know he was very scared. The first thing he said was, ‘Mommy, why’d they shoot him? Ramarley didn’t do anything,’” Constance says. Today, no matter what Constance tells him, Chinnor does not like, nor does he trust, the police. Constance herself has a slightly different perspective.

“I don’t believe all of them is bad. They have a lot of bad apples they have to get rid of. In this country you need police, but the rate they are going is not good,” Constance says on the high rates of murders at the hands of police. Constance’s family came from Jamaica for a better life, like many immigrants to this country. She did not come to live in a country where legally sanctioned, racist violence was tolerated.

“The first thing when it happened, that’s the first thing my mom said, is how could it happen here [in the USA]? This is the place where you are supposed to be safe inside your home. This is the person your kids are supposed to go to for help. Worse than that is that [the police officer] is still free,” Constance says.

This January, New York City paid Constance’s family $3.9 million in a settlement. However, Ramarley’s killer is free and is still a part of “New York’s Finest.”

Ramarley’s murder did not get national attention at the time because it was right around the time of the murder of Trayvon Martin and the death of celebrity Whitney Houston. When it was in the media, Ramarley’s character was completely demonized. The police claimed he had drugs and was running away. Running away from the police when you are not being detained is not a crime. Ramarley grew up in a community where Black and Latinos are criminalized for the color of their skin and their EBT cards.

“Black and Latinos are the targets. Anything is possible. A lot of times these kids end up in the system. There’s nothing for these Black boys to go to. A lot of them come from the streets,” Constance says.

Ramarley was born in the States, but he was always so proud of his Jamaican identity. “He would tell people he was from Jamaica. He would tell people stories as if he was from there,” Constance laughs. She misses Ramarley’s pride. He would go get a haircut and just stare at his mom until she would compliment him. It was an ongoing joke they had.

“He was just a fun person. He had a funny personality. His siblings still always talk about jokes he would make and pranks,” Constance says.

Constance has become an important activist in the struggle for Black Lives to Matter in this country, and she has become an important figure for other families of victims of police brutality.

“I support other families. Many of these families I support, not just police violence, [general] gun violence also. It’s good to be out there and help families out there for advice,” Constance says.

Constance sees justice as her son’s killer going to prison, along with other members on the team. They all illegally breached her home. “I know my son is not going to come back, but it’ll set an example like you can’t do this,” Constance says.

Constance’s son Chinnor is now 9, and her older daughter is 25. “My daughter actually knows the law, she was supposed to be a police officer before this happened. She passed the tests and everything, and they told her it was too stressful for her [after the incident],” Constance says.

Still, Chinnor and Constance’s mother disdain the police. Her mother gets angry when she just sees the police.

Constance is proud of the Black Lives Matter movement and commends the work it’s done thus far, and continues to be an empowering resource to other mothers.

She tells them, “Stay strong. The system is made to beat us down. There are some mothers who never fight. They drag the cases out. They make you wait four or five months for an indictment.” Ramarley’s case received an indictment, but nothing came of it. Despite the heinous crime, Constance will not leave the Bronx.

“Wherever I go, it doesn’t matter where you go. Once you’re Black, you’re always a target.”

Tess Raser, originally from Chicago, is a teacher in Brooklyn and an active member of the growing Black Lives Matter movement. She works with various groups, including We the People and the Stop Mass Incarceration Network.