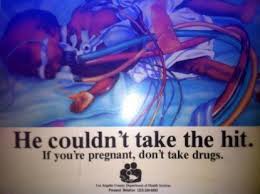

But it turns out the phenomenon of these sensory-deprived, drug-addicted newborns was just a myth — and there’s even a study to prove it.

In a groundbreaking project led by Dr. Hallam Hurt, then the chair of neonatology at Albert Einstein Medical Center, researchers followed the babies of more than 200 mothers who smoked crack during their pregnancy between 1989 and 1992. After 25 years of tracking these babies, Hurt’s team found …nothing.

There were no differences in the health and life outcomes between babies exposed to crack and those who weren’t.

The whole phenomenon of crack babies was a media-fueled myth.

Newspaper profiles, television specials, years of cruel jokes — it all was hysteria based on an illusion.

But in fact, the fuel was provided by an entity even more powerful than the media — it came from the federal government. As law professor Michelle Alexander revealed in her book, The New Jim Crow, when President Ronald Reagan declared a War on Drugs in 1982, recreational drug use in the U.S. was in serious decline. Reagan’s declaration of war tapped into a growing public sentiment against illegal drug use. So the declaration was more about politics than about drugs presenting an actual danger to the nation.

The Reagan administration was trying to make his pitch to white people, so it was easy to construct Black people as the enemy in the War on Drugs. This has led to mass incarceration that has imprisoned millions and devastated Black communities across the U.S. The administration made crack into the monster it needed to create the modern prison industrial complex.

Alexander said the administration even used publicists to help create the myth of the uniqueness of crack, a new incredibly addictive superdrug. At the start of the crack scare in the fall of 1985, the news media unleashed a series of startling stories about newborn infants who allegedly suffered severe and permanent health damage as fetuses because their mothers ingested cocaine during pregnancy. But as Hurt and other researchers found, the impact of cocaine exposure on newborn health and development was, at best, greatly exaggerated in media accounts.

In a profile on Al Jazeera America, Jaimee Drakewood revealed the pain she has struggled with for years knowing the stigma attached to her as a former “crack baby.”

“I immediately get defensive,” Drakewood, now 25, says about hearing the term. “It’s another stigma, another box to put me in. It bothers me because it feels like I already had my life written off before I was able to live it.”

After using drugs while she was pregnant with Jaimee, her mother, Karen Drakewood, was worried about whether she had harmed her child, so she eagerly signed up for Hurt’s study 25 years ago.

As with the other children Hurt followed, Jaimee Drakewood is doing extremely well, healthwise, and is about to receive her bachelor’s degree from Tuskegee University in Alabama.

Her mother has been clean for more than 10 years and now works for Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections.

Karen Drakewood told Al Jazeera that Hurt’s study actually helped her because it was the first time someone viewed her as a whole person and not just as an addict.

“She was a whole person,” Hurt responded. “Everybody’s got their demons. Her demons were seen in the public eye, but we all have our demons. And I think knowing that helps us respect people.”