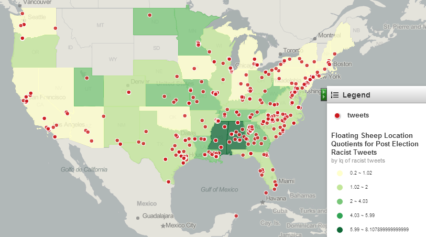

Oregon has one of the smallest Black populations in the entire country—less than 3 percent of its population is Black, according to a 2013 estimate by the U.S. Census Bureau.

And that’s exactly how its founders would have wanted it.

While the average high school history class talks about slavery and racism as if they were problems contained in the Deep South, Oregon’s past is yet another reminder of how false that really was.

The entire state was founded on a set of laws and general beliefs that oppressed the Black community and made daily life extremely hard for them.

To be fair, many states outsides the Confederacy were founded on the same principles but Oregon was unique in the fact that they were willing to put their racial bias on paper.

“What’s useful about Oregon as a cast study is that Oregon was bold enough to write it down,” Walidah Imarisha, an educator and expert on Black history in Oregon, told Gizmodo. “But the same ideology, policies, and practices that shaped Oregon shaped every state in the Union, as well as this nation as a whole.”

Oregon didn’t stop at posting “White Trade Only” signs in business windows or turning a blind eye to threats made against Black citizens. Leaders also wrote laws specifically to keep Black people out of the state.

Ever since Oregon was granted statehood in 1859, it actually forbade Black people from living, working or owning property in the state.

It was only in 1926 that Black people were even allowed to move to Oregon.

The majority of people in the state agreed that they were not in support of slavery, but they still wanted nothing to do with the Black community.

So for the natives that had already settled in the land and any other Black people within the state’s borders, they were given two years to pack up and leave.

In 1844 the Legislative Committee passed a provision that required all free Black people to leave the state within two years or be subjected to flogging. The provision said that the floggings, or beatings, would continue every six months until they left the state.

By 1845, that piece of legislation was revised.

The new provision stated that Black people still left in the state’s borders would be “publicly for hire” to any white person that would get them out of the state.

It is generally believed that the provision was giving white people the right to enslave Black people as long as they would take them out of the budding white utopia.

Perhaps even more concerning was the fact that the legislators believed they were acting morally by keeping Black people from living around white people.

“We were building a new state on virgin ground,” one noted “pioneer” voter of the legislation said during a reunion in 1898. “Its people believed it should encourage only the best elements to come to us, and discourage others.”

This voter eventually became a Republican state senator.

It was one of the early examples of racially coded language in the U.S.—his reference to white people as the “best elements” and Black people as “others”—and it essentially laid the groundwork for what would be years of oppressing and abusing any Black people who dared to enter the state.

“If you look at some of the recruiting materials, in essence they’re saying come and build the kind of white homeland, the kind of white utopia that you dream of,” Imarisha added. “Other communities of color were also controlled, not with exclusion laws, but the populations were kept purposefully small because the idea behind it was about creating explicitly a white homeland.”

As years flew by, the state’s idea of a white utopia was thwarted by federal law.

While the state ratified the Fourteenth Amendment in 1866, it rescinded its ratification in 1868. As many scholars pointed out, the move was a strategic one that sent a message to the Black community to steer clear of Oregon.

Before that time came, however, people of color were left struggling to find a place where they could have a sense of community. That’s where the Golden West Hotel came into play.

The unique establishment was owned and operated by Black people in Oregon.

This means white people tended to steer clear of the establishment, making it a hot spot for Oregon’s Black community as long as it could keep its doors open.

Portland authorities often tried to shut the Golden West down by making up false charges of prostitution and gambling. At one point they even claimed the owners didn’t have the “proper licenses” to keep the place open.

It’s also important to note that even the Golden West wasn’t a perfectly safe place for Black people. White people would sometimes make their way inside simply to harass or threaten the Black patrons.

Even with those conditions, however, it was the best place the Black community had to come together.

With the arrival of the Ku Klux Klan in 1922, it seemed like Oregon would never grow to be a welcoming place for Black people.

The Klan quickly garnered thousands of members, roughly 9,000 men in Portland alone, and struck fear into the Black community throughout the state.

To be clear, this was no organization full of your average joes. Politicians at every level were involved with the Klan and worked closely with the white supremacy group to attempt to rid the state of all Black people.

As the Black population quickly decreased, so did Klan membership.

Even that didn’t bring an end to racism in the state, of course.

Businesses still asked people of color to steer clear of their establishments and one 1999 documentary features the account of one man who recalled signs downtown that read, “We don’t serve Negroes, Jews or dogs.”

So as the state still struggles to create an accepting environment for African-Americans, it’s important to realize just how much Oregon’s racist history already laid the foundation for it to become the place it is today—a state where there seems to be far more Confederate flags than Black faces.

It also serves as a reminder that racism was never a problem that was contained to one region of America—it swept the nation, regardless of whether legislatures were bold enough to put it in writing or not.