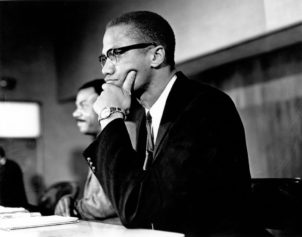

Perhaps nothing spoke more of Malcolm X’s innate feel for the power of photographs than Robert L. Flora’s iconic black-and-white portrait of the late national spokesman for the Nation of Islam.

Taken in Los Angeles on May 28, 1963, the photo depicts the civil rights leader and his associates as they await the verdict of an all-white jury that was deliberating the fate of 14 Black Muslims accused of assaulting police officers. The pictorial magazines and tabloid newspapers they were reading to pass the time nearly crowd out the image and tell more about the nation’s turbulent social climate of the time than any story ever could.

It was Malcolm who allowed Flora permission to take the picture, signifying his keen awareness of that medium’s ability to best deliver a powerful message and shape critical American public opinion, argued Maurice Berger, a research professor and chief curator at the Center for Art, Design and Visual Culture at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and consulting curator at the Jewish Museum in New York, in Wednesday’s New York Times.

The men in the picture are focused on articles about the Nation of Islam. The Life magazine story that engrosses Malcolm was typical of the oft-derisive coverage of the Black Muslims in the mainstream press: “The White Devil’s Day Is Almost Over: Black Muslim’s Cry Grows Louder,” screams its headline.

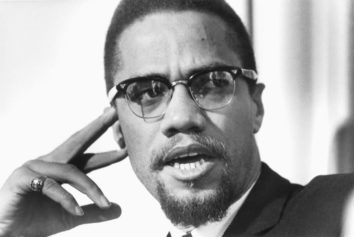

Malcolm X was one of the most media-savvy black leaders of the period. By the time of his assassination in 1965, he was also one of the most photographed and televised, appearing on hundreds of local and national interview programs.

Handsome, charismatic and articulate, he provided the mainstream news media with a compelling narrative that would enrapture readers everywhere. His soliloquies about a burgeoning black community calling for self-determination, racial separatism and independence to be achieved by “any means necessary,” including violent insurrection, resonated around the world.

Malcolm’s understanding of the power of the media allowed him to have a unique national platform to espouse a radical worldview, one that rejected the nonviolent practices and integrationist goals of the mainstream civil rights movement.

Prior to his death, Malcolm’s view of the latter grew more conciliatory following his pilgrimage to Mecca.

Only the Nation of Islam’s weekly newspaper, Muhammad Speaks, and, to a lesser extent, the Negro press, regularly provided positive press. The mainstream news media, stoked by his fierce, sometimes inflammatory rhetoric and its own anxieties around race, afforded little more than negative and sensationalistic coverage, much like the Life article featured in Flora’s photograph.

Malcolm viewed the “white press” as more or less a lost cause, but nevertheless engaged it and, at times, even outsmarted it.

Many blacks at the time rejected the Nation of Islam’s religious orientation, fundamentalism, political extremism and cultural insularity. But many were also skeptical of the mainstream movement that asked its supporters to patiently turn the other cheek when done wrong.

A keen steward of the Nation of Islam’s visual representation, Malcolm X often carried a camera, his way of “collecting evidence,” as Gordon Parks once observed. When photojournalists visited the community, he tried to steer them toward the kinds of affirmative images – shots of contented family life, children at play and school, and thriving businesses and institutions – that might subtly ameliorate the negative texts that he knew would inevitably accompany them.

In the end, it was the same precision and high-level sophistication of Malcolm’s self-presentation that reads most vividly in Flora’s photograph. His fashionable, well-tailored clothes, chic eyeglasses, relaxed yet formal posture and refined hand gesture were important details meant to convey both composure and authority.

No matter Flora’s motivation for taking the picture, his subject, much as always, succeeded in getting his message across.

And through the myriad of ideas he communicated through photographs, Malcolm X transformed the Nation of Islam, increasing its membership by tens of thousands and allowing its leaders to influence African-American public opinion for decades to come.