The legal odyssey of Georgia death row inmate Warren Lee Hill may have moved closer to his execution, as a federal appeals court today denied his petition for the court to consider new evidence, thus lifting the stay that had rescued Hill from lethal injection in February.

In a 2-1 vote, the 11th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled that Hill and his attorneys had not proven that his circumstances require them to consider his case once again—namely, that three doctors who examined Hill in 2000 and diagnosed that he was not mentally retarded and now have signed affidavits stating their 2000 diagnosis was wrong does not constitute new evidence in his case.

As a result, although all medical specialists who have examined him have determined that he is “mentally retarded” (the non-politically-correct term still used by the courts), the federal appeals panel has concluded that Georgia can go ahead and execute Hill.

Hill had his execution halted at the last minute on two previous occasions—in July 2012 just 90 minutes before the lethal injection was to be administered and in February 2013 just 30 minutes before the execution time. In both cases, the stay of execution was centered around a change in the way Georgia conducted lethal injections, from a three-drug injection method to a single drug.

“We are deeply disappointed that the 11th Circuit United States Court of Appeals found that procedural barriers prevent them from considering the compelling new evidence in Warren Hill’s case,” Hill’s lawyer Brian Kammer said in a statement. “The new evidence shows that every mental health expert ever to examine him finds that Mr. Hill has mental retardation and is thus ineligible for execution according to the constitution of the United States.”

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled a decade ago that the mentally retarded should not be executed because their mental state “places them at special risk of wrongful execution,” but Georgia is the only state that requires defendants to prove their mental retardation beyond a reasonable doubt — which experts contend is almost an impossible standard.

Hill was to be put to death for the brutal killing of Joseph Handspike, another inmate in the prison where Hill was serving a life sentence for the 1986 killing of his girlfriend, whom he shot 11 times.

Hill’s case attracted an outpouring of support and outrage, from The New York Times editorial page to former President Jimmy Carter. Even the family of the victim does not wish to see Hill executed and has submitted an affidavit supporting commuting Hill’s death sentence to life without the possibility of parole, citing his mental condition.

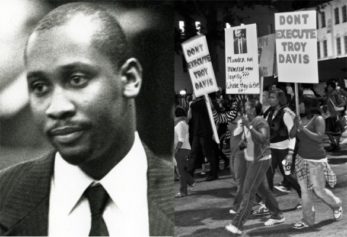

If Hill is executed, it would be the first completed death sentence in Georgia since the controversial execution of Troy Davis, who was killed in 2011 despite substantial evidence of his probable innocence.

Much of the argument by the federal appeals court focused on whether the change of heart by the three doctors constituted new evidence in the case. Two members of the three-judge panel concluded that the change by the doctors was not new evidence.

The judges ruled in essence that it would be a dangerous standard to reopen cases just because old witnesses wanted to change their testimony.

“If all that was required to reassert years later a previously rejected claim was a change in testimony, every material witness would have the power to upset every notion of finality by simply changing his testimony,” the majority wrote. “And, as this case illustrates, opinion testimony can be changed with great ease (indeed, even without seeing Hill in 13 years, administering any new tests, or reviewing new documents, three witnesses pivoted their positions 180 degrees).”

But in a powerful dissent in which she calls Georgia’s standard “preposterous,” Judge Rosemary Barkett lashed her colleagues for using procedural arguments to get around the fact that they were about to allow Georgia to execute a man that all medical experts now agree meets the standard for mental retardation and thus should be protected by the Supreme Court ruling.

“The idea that courts are not permitted to acknowledge that a mistake has been made which would bar an execution is quite incredible for a country that not only prides itself on having the quintessential system of justice but attempts to export it to the world as a model of fairness,” Barkett wrote in her dissent. “Just as we have recognized that a petitioner who ‘in fact has a freestanding actual innocence claim . . . would be entitled to have all his procedural defaults excused as a matter of course under the fundamental miscarriage of justice exception,’ I see no reason not to accord the same consideration to one who has a freestanding claim that he is, in fact and in law, categorically exempt from execution….[The federal habeas statute] should not be construed to require the unconstitutional execution of a mentally retarded offender who, by presenting evidence that virtually guarantees that he can establish his mental retardation, is able to satisfy even the preposterous burden of proof Georgia demands.”