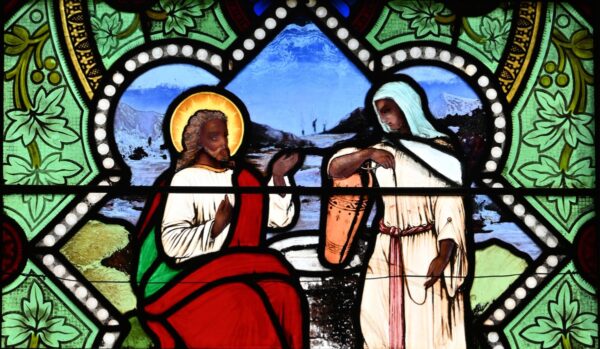

The owner of the nation’s oldest depiction of Jesus Christ as a person of color in stained glass is currently searching for a cultural institution that can not only preserve the window but showcase it publicly to the world for religious and academic study.

The 12-foot tall, 5-foot-wide window has prompted a new conversation about race and gender in the 19th century in academia, according to The Associated Press.

While scholars agree that the almost 150-year-old iconography does portray a person with intentionally dark skin, they wonder if the person who commissioned the piece was making a political statement about the two women listed in the work’s credits.

Chief among the questions was if the window, initially installed in the St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, a Greek Revival worship body in Warren, Rhode Island, in 1878, was loose commentary or critique of the way America saw the Black or brown person at the time.

Related: Nigeria Unveils Africa’s ‘Biggest Statue’ of Jesus

“It was a statement that Jesus is the color of the Jesus in your heart, all around the world,” said Virginia Raguin, a professor of humanities emerita at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, and an expert on the history of stained-glass art, told AP. “If Jesus is my brother and I am Black, Jesus is Black.”

The biblical Jesus would have been a first-century Palestinian Jew, a man of color.

A metaphoric reference to Jesus as the Son of Man in Revelations 1:14-15 states that he has “feet of burnt brass” and “wooly hair.” Many use this quote to connote race, supporting the idea that a historical representation of Jesus is darker than the Eurocentric depiction of him.

The stained glass image seems to debunk the long history of Jesus having soft brown hair, blue eyes and the racial hierarchy that image represents. It also aligns with what most scholars believe to be fact: Jesus would have had dark hair, dark eyes, and dark skin.

So much discussion has prompted the owner of the window to reconsider her own possession of such a thought-provocative piece.

“I think this belongs in the public trust,” Hadley Arnold, the window’s owner, said to the wire service. “I don’t believe that it was ever intended to be a privately owned object.”

A woman named Mary P. Carr commissioned the Henry E. Sharp studio in New York to make the window. She dedicated it to her aunts, Mrs. Hannah Bourne Gibbs and Mrs. Ruth Bourne DeWolf, according to The Associated Press.

Ruth DeWolf is believed to have been a guardian for Carr.

Both women were socialites who supported causes that demonstrated an interest in African-American lives — providing them with alternatives to the discrimination found in the country at the time.

As philanthropists, they were donors to the American Colonization Society, an organization founded to assist in one of the earliest back-to-Africa movements that helped send freed slaves to Liberia in Africa.

According to the U.S. government, Liberia was founded in the 1800s by a group of white Americans from the ACS as a solution “to deal with the problem of the growing number of free Blacks in the United States by resettling them in Africa.”

Originally the group consisted of both abolitionists and slaveholders, including former President Thomas Jefferson, and Blacks and white. But abolitionists left the movement because of the growing anti-integration sentiment within the body.

The work of the ACS helped Liberia become the second Black republic in the world after Haiti.

The sisters were a part of the abolitionist movement.

Ironically, Gibbs and DeWolf both married men whose families were deeply invested in the trans-Atlantic slave trade. Gibbs’ husband was a sea captain who worked for DeWolf’s husband’s family. The DeWolf family was one of the nation’s leading slave-trading families in America.

The patriarch of the DeWolf family was former U.S. Sen. James DeWolf. During the height of the operation, sources say, the family transported approximately 12,000 enslaved Africans across the Middle Passage.

In 1789, after one of the enslaved women was sick with smallpox, DeWolf had her tossed overboard — and was later prosecuted for her murder. He was, however, found not guilty, as the courts determined it was his duty to do so as the sea captain.

Against this familiar backdrop, these women not only supported the back-to-Africa movement but also funded the founding of a different church in the area with true egalitarian principles.

Though St. Mark’s did not leave behind many records regarding the commission, one preacher said during remarks after the unveiling “the peculiar fitness of the scripture scenes portrayed, as in the exquisite beauty of the workmanship, is a most suitable expression of those Christian characters in whose memory it has been erected.”

Interestingly, it was only discovered that the windows had human figures with brown skin in 2020.

In 2010, a family purchased the 1830-constructed building and converted it into their home. It was not until a decade later, after replacing the windows with clear glass, they noticed Jesus was depicted differently from in other churches they knew.

“The skin tones were nothing like the white Christ you usually see,” said Arnold, the homeowner who teaches architectural design in California and has an art history degree from Harvard University.

Raguin echoed Arnold’s remarks, saying, “This window is unique and highly unusual. I have never seen this iconography for that time.”

Art-Net describes the window as telling a narrative that combines two biblical stories: Jesus and the Samaritan woman and the Nazarene with the sisters Martha and Mary and records all four figures having dark brown skin.

Arnold and her family allowed Raguin and her colleagues to inspect the piece of art and they confirmed that not only does the image indeed show that Jesus is shown as having dark skin, but that the effort was intentional.

“Colors in glass can flake off, but they don’t change like oil paint because they are fired into the glass,” Raguin explained.

Now the family is just curious about how the decision to make Jesus a man of color at that time transpired.

“Is this repudiation? Is this congratulations? Is this a secret sign?” Arnold ponders, considering the history of both women that the window was commissioned in honor of.

“We don’t know, but it would appear that she is honoring people of conscience, however imperfect their actions or their effectiveness may have been,” Arnold said. “I don’t think it would be there otherwise.”

Raguin has a theory that Carr wanted the art to reflect the shame the family may have felt about the way Sen. DeWolf, who by this time had died, made the family’s fortune.

The stained-glass scholar also wanted to draw attention to the scene being portrayed in the window. It is of Jesus talking to his friends from Bethany, Martha and Mary (the sisters of Lazarus). In the episode, Jesus is engaging the women as equals — a point often lifted in the synoptic gospel of Luke.

While the questions might never be answered, the impact of the religious iconography being made public has reverberated through the community.

Linda A’Vant-Deishinni, the former executive director of the Rhode Island Black Heritage Society, told AP that as an African-American with indigenous American heritage, “The first time I saw it, it just kind of just blew me away.”

Arnold is currently searching for a museum, college, or another institution that can preserve the window and showcase it for religious and academic study.

Until then, the window remains propped up in a corner of the house in a wooden frame, not far from where pews in the old church once stood.