Black Houston residents have disproportionately suffered for decades through exposure to hazardous chemicals that have killed generations of Black residents. Yet, the head of the agency meant to ensure the state has clean air and water shied away from acknowledging the presence of “environmental racism,” even though studies show it exists.

More than 100 Houston residents took to the Texas Capitol this week to plead with the agency to protect them from environmental hazards. Among their concerns is the agency’s failure to regulate industrial emissions from Union Pacific Railroad that has created a cancer cluster in the predominantly Black Fifth Ward.

Many accused the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality of failing to properly screen permits for industrial plants and authorizing 150 concrete plants near residential areas, schools and churches. The chemicals produced by companies evolved into hazardous and deadly toxins.

“I say to the TCEQ, stop killing us and giving ammunition to Big Money to kill us slowly,” Houston resident Cara Deshawn said.

Several other “sacrifice zones” have been identified in other Black communities across the nation. Reports show residents in predominantey Black neighborhoods in Louisiana, Mississippi, West Virginia and Pennsylvania historically have lived in hotspots for cancer-causing fumes.

An annual report released by the Energy Policy Institute at the University of Chicago earlier this month found that air pollution, which is usually a mixture of dust, smoke and other particles, could decrease life expectancy by more than two years.

“This impact on life expectancy is comparable to that of smoking, more than three times that of alcohol use and unsafe water, six times that of HIV/AIDS, and 89 times that of conflict and terrorism,” the Energy Policy Institute report says.

Black American elderly people are three times more likely to die from exposure to fine particle air pollution than white Americans over 65 years old, a recent report by the Environmental Defense Fund shows. It also found Black and Hispanic people are six times more likely to visit the emergency room for air pollution-triggered childhood asthma than white people.

Reports show that residents in Fifth Ward have been exposed to creosote, a chemical once used to treat wooden rail ties at Union Pacific’s old railroad facility. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says the chemical could pose a cancer risk to humans. Health experts say it has seeped through the soil, including under houses in Fifth Ward.

Texas officials have found higher rates of lung and esophagus and throat cancer among adults in the neighborhood, and children there have been diagnosed with leukemia at a higher expectancy rate.

Houston resident Kathy Blueford-Daniels told Texas lawmakers that most residents in Houston’s Black community have little choice in the areas they can live. Many have been redlined or priced out of other areas.

“For decades, communities of color have been targeted for polluting environmental hazards that others did not want,” Taylor Bacon of Environmental Defense Fund told Atlanta Black Star. “They’ve been targeted for freeways, factories, power plants, landfills and the resulting inequities and pollution exposure are further aggravated by discriminatory disinvestment, limited access to health care, intergenerational poverty and higher vulnerability to the health impacts of air pollution.”

After the Civil War, Black workers chose to live in the Fifth Ward because it was close to railroad yards and the Houston Ship Channel. However, by the 1960s, residents could detect a “heavy” smell and feel an air thick with oil and gasoline, according to reports.

Residents started getting sick in numbers in the 1970s. Even as state officials find cancer clusters in the area as recent as 2021, the Texas Commission of Environmental Quality has been slow to hold Union Pacific accountable for the pollution, residents and advocates say.

Borris Miles, state senator for Houston, said Black neighborhoods have been targeted for “undesirable land use” and face a lack of enforcement of zoning and environmental law because of environmental racism.

Black Texans also face pollution from concrete plants. About 44 percent of Houston’s concrete plants are in majority Black and Hispanic neighborhoods, a Houston Chronicle analysis of Harris County data shows. The paper also found that when plants were approved in white neighborhoods, the area tended to be less densely populated.

“Some of the facilities have been in the district for over 100 years, and some of them are brand new,” said Miles, who has been a strong advocate against environmental racism.

“What these facilities have in common is that they are largely located in poor minority neighborhoods” in his district and “across the state of Texas. Again, this is the definition of environmental racism.”

The review panel of legislators and members of the public held the meeting to review the commission’s performance and the need for its existence. The panel also mulled over an evaluation report that found commissioners have become “reluctant regulators” who are creating “a concerning level of distrust,” “rubber-stamped” permits and have allowed industrial companies to “self-police.”

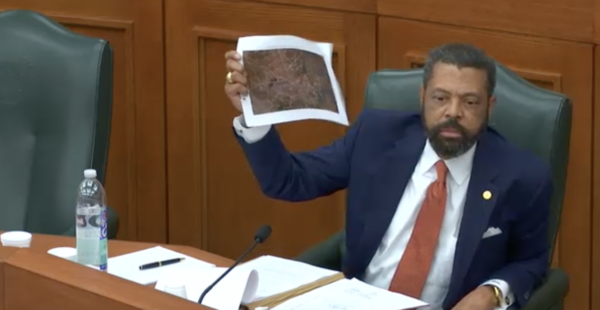

Miles drilled commission chairman Jon Niermann about environmental racism in the agency’s regulation of the concrete plant permits. In response, the chairman said he “was not sure what do with” the “term ‘environmental racism.’ “

“Do you think economic development should be put over health and safety and welfare of the citizens of Texas?” Miles continued.

“Absolutely not,” Niermann replied.

However, Niermann said he was “not quite sure how to approach” Miles’ question on whether he believed there’s a problem with permitting concrete plants in Houston’s Black communities.

“Some communities in Texas have a greater concentration of regulated activity than others. That is just a plain fact,” Niermann said. “Is there a correlation between race and those concentrations of regulated entities? I’m not going to dispute that. I don’t know one way or another. We’ve never done the analysis.”

Miles responded by laying out the definition of environmental racism and detailing the experiences of Fifth Ward residents and other Black communities in his district.

The senator also held up a map with several red dots, which he pointed out showed the numerous plants in his district.

“If this does not look like a rubber stamp, what does?” Miles said.