San Francisco became the first U.S. city to ban facial recognition technology this week, a groundbreaking move cheered by privacy advocates everywhere. Some critics say the ban goes too far, however, while others argue it doesn’t go far enough.

The legislation, passed Tuesday, will force city departments to disclose what surveillance technology they use and will require approval from the Board of Directors on any new technology that collects or stores data, according to The San Francisco Chronicle.

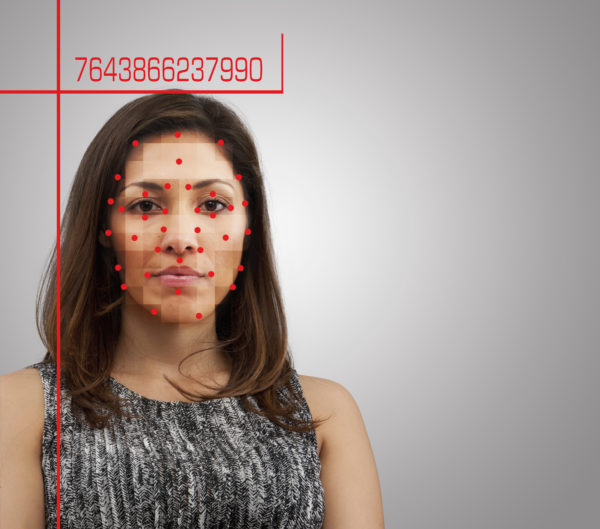

The San Francisco’s citywide ban on facial recognition technology will go into effect next month. (Photo by John M Lund / Getty Images)

Board members approved the ordinance in an 8-to-1 vote, but they have to vote on it once more before it heads to Mayor London Breed‘s desk for a signature.

“This is really about saying we can have security without being a security state,” said Supervisor Aaron Peskin, who authored the bill. “We can have good policing without being a police state. Part of that is building trust with the community.”

Sole dissenter Supervisor Catherine Stefani took issue with the legislation, however, arguing that an outright ban on facial recognition would bar the city’s police access to useful crime-fighting software. Stefani also expressed concern that forcing law enforcement to disclose their current surveillance technology, and seek approval before getting new technology, would only add to their workload.

“I am not yet convinced, and I still have many outstanding questions,” she said, as reported by the Chronicle. “[But] that does not undermine what I think is a very well-intentioned piece of legislation.”

The San Francisco Police Department currently doesn’t use the technology and likely won’t be acquiring it in the future. Meanwhile, the city’s airports are exempt from the ban because they’re federally regulated.

The use of facial recognition technology has become common among both public and private entities, but it has some major shortfalls — particularly when it comes to identifying people of color. Not only has the technology been blamed for countless false arrests, social justice activists warn that it can be used to track people’s locations and target resisters, even when they haven’t committed a crime.

Last month, a New York man filed a $1 billion lawsuit against Apple after he says a facial recognition system at one of its stores falsely linked him to a string of thefts at Apple stores, leading to his arrest. Apple claims it doesn’t use the technology in its stores.

A similar incident occurred last July when Amazon’s facial recognition tool mistakenly matched the faces of 28 members of Congress with criminals in mugshots and disproportionately misidentified people of color.

While the new pro-privacy ordinance is being hailed as a step in the right direction, analysts with Technology Review.com pointed out that the ban only limits city government entities. Private, non-governmental entities — including stores that provide consumers with targeted ads and school surveillance systems — will all still be able to use the technology.

Regulating who can and cannot use surveillance in the private sector can get complicated fast.

“When your narrative is ‘government surveillance,’ that tends to have powerful resonance,” Joseph Jerome, policy counsel for the Privacy & Data Project at the Center for Democracy and Technology,” told the outlet. “When you’re dealing with the private sector, we start having debates about what constitutes beneficial innovation.”

The emerging technology remains largely unregulated across the U.S., and now a handful of cities are looking to change that. The city of Oakland is set to vote on a similar facial recognition ban later this year, and officials in Somerville, Massachusetts, are still pondering the idea.

“With all the changes in tech that we may not understand today, it is important to bring its use to light, while balancing the need for public safety,” Supervisor Ahsha Safai told the Chronicle.

The new ordinance is set to go into effect next month.