MINNEAPOLIS (AP) — When an unarmed white woman who called 911 to report a crime was fatally shot by a black, Somali American police officer in Minneapolis, the racial dynamic seen in many police shooting cases in the U.S. was flipped on its head, and a different narrative emerged.

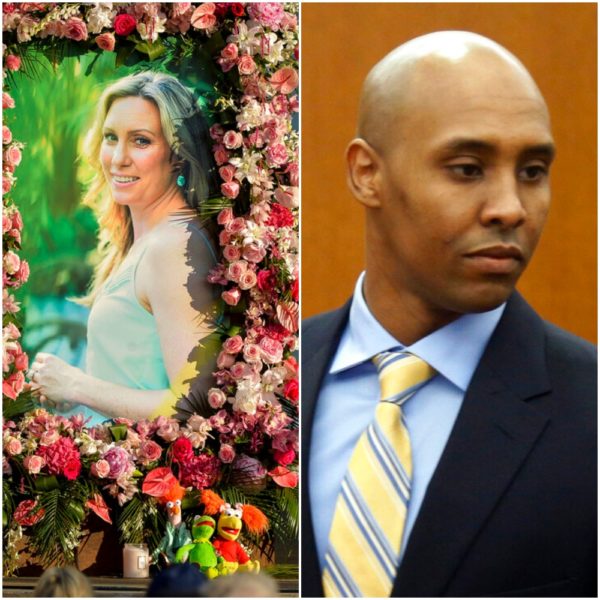

Justine Ruszczyk Damond was immediately portrayed as the innocent victim she was, a peaceful woman who was trying to help someone else by calling 911 to report a possible rape in the alley behind her home. The officer, Mohamed Noor, was sharply criticized by the then-police chief, while others wrongly alleged he was a fast-track affirmative action hire for a city trying to diversify its police department.

Noor, 33, was charged — a rarity when an on-duty officer shoots someone — and is now on trial for murder and manslaughter in the July 2017 death of Damond, a 40-year-old dual Australian American citizen.

While Minneapolis police spokesman John Elder said race is never a factor in the department’s personnel decisions or internal investigations, some activists say it’s been part of the equation from the start — from the public portrayals of Damond and Noor, to the fact that Noor was charged and fired from the police force. When the shooting happened, Somali Americans felt singled out because then-Chief Janee Harteau spoke out against Noor’s actions instead of reserving judgment, and the police union was largely silent.

“Race and affluence has played a role in terms of how this case is being handled,” said Nekima Levy Armstrong, a civil rights attorney and former president of the Minneapolis NAACP.

Noor shot Damond as she approached his police SUV. While prosecutors say there’s no evidence of any threat to justify deadly force, Noor’s attorneys argue that he heard a loud bang and feared he and his partner were being ambushed.

A spokesman for the prosecutor’s office had no comment on the role of race in the case. But potential jurors were asked questions such as whether they’ve had negative experiences with Somalis and about their potential biases. The jury of 16 people, four of whom are alternates, includes six people of color.

While each police shooting is different, with no two victims the same and officers facing different real or perceived threats in every situation, activists note that while Damond is seen as an innocent victim, black people shot by police are often made to look like villains.

“We want black and Latino and native victims of police violence to be treated like her,” said Shaun King, a Black Lives Matter activist and writer. “You can have the sweetest person ever killed, but if they are black, poor, and in a particular zip code, the portrayal is nothing like the portrayal that she received in this case. I felt like from day one she was treated the way every victim of police violence should be treated.”

Attorney S. Lee Merritt has represented families of multiple black people killed by police. One was Botham Jean, who was shot in his own Dallas apartment by an off-duty officer who has said she mistook his door for her own. After the shooting, police sought a search warrant that resulted in the discovery of marijuana in Jean’s apartment — something Merritt says was an attempt to smear the 26-year-old victim. Dallas police have not responded to that criticism; the white officer who killed Jean awaits trial.

Convictions for police officers are rare. But Merritt, who also represents the family of Antwon Rose II, an unarmed black 17-year-old who was killed last year while running from an officer, believes Noor will be convicted. The white former East Pittsburgh officer who shot Rose was acquitted last month after saying he perceived a threat, which is the legal standard.

King also said he wouldn’t be surprised if Noor were convicted, saying that it’s hard for a jury to identify with an immigrant, Muslim, black man. He said the defense of fearing for one’s life can work for white officers, but he has a hard time believing it will work for Noor.

Many activists say they’re not advocating for leniency for Noor, but for equity — and for overall changes to policing in the U.S.

The problem, Levy Armstrong says, is in the systemic nature of police violence and the public’s willingness to rubber stamp it, as long as an officer says he or she was fearful.

And while she and others want Noor to be held accountable, “I don’t want to see a Somali, black, Muslim officer be scapegoated when the rest of the system remains intact.”

In the days after Damond’s death, activists in Black Lives Matter and other groups came out in strong support of her family and friends. They marched in the streets and called for then-Mayor Betsy Hodges to resign.

Among them was the mother of Philando Castile, a black man who was shot during a traffic stop in Minnesota in 2016 after he informed a police officer he had a firearm. The officer, who is Latino, was acquitted in 2017.

Valerie Castile said listening to the officer’s defense team try to make her son sound like a horrible person because he had marijuana in his system was “heartbreaking.”

“No life is any different than the other. It’s a tragedy that we lost our loved ones to someone who is supposed to protect and serve,” she said. “But it’s so unfortunate in our country people are treated differently.”