RICHMOND, Va. (AP) — A movement to rename a Richmond, Virginia, thoroughfare for groundbreaking black tennis player Arthur Ashe Jr. is cresting just as the state finds itself in turmoil over a blackface scandal involving the governor and attorney general.

The man behind the street renaming says the confluence of the two unrelated developments involving race and history could become an opportunity to start a conversation about race at a pivotal time.

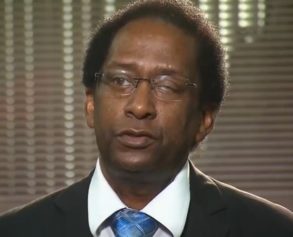

“If we can rename the Boulevard after him, it would be a huge cultural step forward. This is where we can start with reconciliation and we can start talking about the issues,” says Ashe’s nephew, David Harris Jr.

“It would be an opportunity for the City Council to be leaders on this. We know what’s going on down the street at the state Capitol. This would be a way for the City Council to say, ‘We want to show you the way.'”

In this Jan. 10, 2019, photo David Harris Jr., left, the nephew of Arthur Ashe, and Richmond City Council member, Kim Gray, right, look over the tennis courts on the Boulevard which were tennis star Arthur Ashe was banned from in Richmond, Va. The duo are attempting to get the Boulevard renamed for for tennis great Arthur Ashe. (AP Photo/Steve Helber)

Ashe’s once-segregated hometown boasts an athletic center named after him, and a bronze sculpture of Ashe sits among Richmond’s many Confederate statues. But a proposal to rename a historic street for Ashe has been defeated twice since his death in 1993.

A third proposal comes before the City Council for a vote Monday amid the blackface scandal.

Leaders throughout Virginia’s political structure have called on Gov. Ralph Northam to resign after a racist photo on his 1984 medical school yearbook page surfaced recently.

Northam apologized, initially saying he appeared in a photo showing one man in blackface and another wearing a Ku Klux Klan hood and robe. Northam did not say which costume he wore. The next day he said he no longer believed he was in the photo but acknowledged wearing blackface the same year to look like Michael Jackson in a dance contest.

Days after Northam’s admission, Attorney General Mark Herring was forced to acknowledge that he, too, wore blackface in the 1980s while trying to look like a rapper at a college party.

Meanwhile, for all of Richmond’s hometown pride in Ashe, repeated attempts to rename a city street after him have failed. Harris initially resurrected the idea of renaming the street after his uncle last year.

Called simply “Boulevard,” it’s a busy 2.4-mile (3.9-kilometer) stretch dotted with restaurants, museums and stately homes. Modeled after grand European boulevards in the late 19th century, Boulevard was designated as a state and national historic landmark in 1986.

At one end sits Byrd Park, with tennis courts where Ashe was denied access during his childhood because of segregation. The athletic center named for Ashe is also on Boulevard.

City Council member Kim Gray, whose district covers a portion of Boulevard, has sponsored the Ashe renaming ordinance.

Some residents and business owners say they don’t want to change the historic name. Others cite the inconvenience and expense of officially changing their address, including getting new letterhead and signs.

Harris and Gray say they understand those concerns but also believe racism may underlie some of the opposition.

“I find it hard to believe that people get that angry over stationery,” said Gray, who said she’s received racist emails over the proposal.

Longtime residents insist they have nothing but admiration for Ashe but believe there are better ways to honor him than legally changing the name of their street. A group called the Boulevard Coalition wants the Richmond History and Culture Commission to hold citywide community discussions about how to honor Ashe and then make a recommendation to the City Council.

The controversy comes at a time when Richmond, a one-time capital of the Confederacy, has been grappling with calls to remove Confederate statues. Richmond’s Monument Avenue features statues of five Confederate figures, including Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson. Ashe’s statue was erected among those rebel icons in 1996, but only after rancorous debate.

Harris said renaming Boulevard after Ashe would give Richmond a chance to shed its past image and show it has become a progressive city.

“We’ve celebrated things that have been associated with slavery for years. Well, let’s celebrate equality, inclusion and diversity, as opposed to the slave picture we’ve had in Civil War history,” Harris said.

Ashe was the first black player selected to the U.S. Davis Cup team and the only black man to ever win the singles title at the U.S. Open, Wimbledon and the Australian Open. He was also well-known for promoting education and civil rights, opposing apartheid in South Africa and raising awareness about AIDS, the disease that eventually killed him.

Richmond Mayor Levar Stoney urged the City Council last month to approve the change, calling Ashe “one of Richmond’s true champions.”

A 2004 city ordinance says street names indicated on city maps for 50 years or longer should only be changed under “exceptional circumstances.” Gray and Harris say they believe naming Boulevard after Ashe is one of those circumstances.

But City Council member Parker Agelesto, whose district covers part of the street, said his constituents favor an “honorary renaming” that keeps Boulevard as the street’s official name.

“Nobody wants this to be controversial, and Arthur Ashe is not a controversial figure,” Agelesto said. “The question is: How do you make it successful for all parties involved?”