Aliko Dangote leaves the Elysee presidential Palace following a meeting between French President and French and African businessmen on October 7, 2016 at in Paris. / AFP / STEPHANE DE SAKUTIN (Photo credit should read STEPHANE DE SAKUTIN/AFP/Getty Images)

As Donald Trump pursues protectionism for the United States as part of his “America First” policy — amid the disagreement and opposition of economics experts and political leaders even in his own party — others, including the richest man in Africa, are suggesting that the countries of the African continent would be well served to pursue such policies.

Aliko Dangote, a Nigerian businessman and the head of Dangote Cement, is the richest man in Africa and a beneficiary of Nigeria’s restrictions on cement imports, which have allowed him to capture 65 percent of the Nigerian market, as Quartz reported. “If you look at what president Trump is doing right now — not that I agree with what he is doing because they are in a totally different economy to what we are — but if you look at where we are today, where there’s no protection, then you are not going to have any industries,” Dangote said recently at the inaugural Obama Foundation Leaders program in Johannesburg, South Africa. Invoking the lopsided economic relationship between China and Africa, Dangote added that while he does not think the United States should erect tariff barriers, if Africa refuses to maintain restricted markets the continent will become the world’s dumping ground, snuffing out local industries in their infancy.

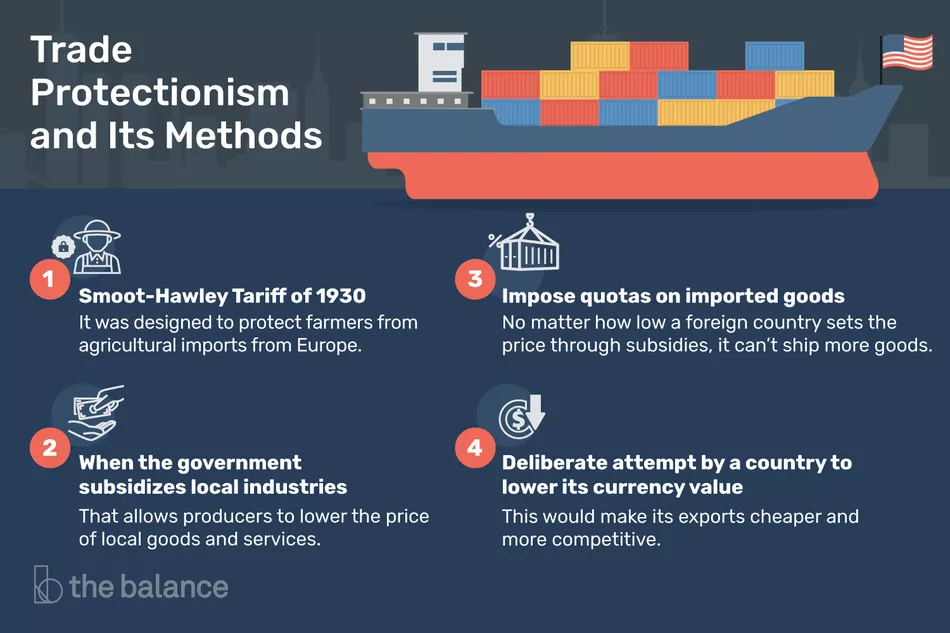

Protectionism refers to official government actions or policies designed to limit foreign trade, often for the purposes of protecting local jobs and companies from international competition. According to Investopedia, the four forms of protectionism are tariffs or import duties, which are levied on products from foreign countries; trade quotas on imports of certain products; restrictions on certain product standards; and government subsidies paid by a nation to assist in the growth of particular industries.

Protectionism may work in the short term in limiting unfair competition and allowing developing nations the time to build capacity to manufacture products that are competitive with other countries. Further, foreign investment in developing nations may not build local expertise and benefit local businesses, particularly if those foreign interests do not share their expertise and techniques. However, there is a longer-term risk of making a nation and its products less competitive in the global marketplace. While protectionism can shield an industry from foreign competitors and allow it to develop a competitive advantage, the practice can also stifle innovation and weaken an industry and slow economic growth. Further, critics argue, tariffs can shelter inefficient producers, lead to higher consumer prices, and raise the cost of doing business in a country, prompting local businesses to move their production offshore to compete with other nations.

One example in favor of protectionism in Africa, and the proposition that free and fair trade for poor countries is nonsense, is Senegal. The African nation removed its trade taxes and found its farming sector wiped out as the European Union dumped subsidized tomatoes and chicken into the country. The collapse of the Senegalese fishing took place in similar fashion as Europeans gained access to Senegal’s waters. Ironically, economic migrants left Senegal in fishing boats for Europe, only to work in slave-labor conditions in a subsidized tomato industry, as The Guardian reported. While rich nations arguably converted to free trade only after they achieved economic superiority, free and fair trade poses a risk of impoverishing already poor nations if done the wrong way.

Sitting on a panel with Dangote was former South African Finance Minister Trevor Manuel. “The idea of building high walls behind which you can do anything doesn’t help the population,” Manuel said, offering that such a posture would only exacerbate inequality, and that developing nations, which lack the institutions that developed nations have, need multilateral trade agreements. “Consumers don’t have a choice, productivity doesn’t actually matter and price doesn’t matter, and the people who suffer are actually the poor in the country,” Manuel added. He also predicted that the tariff war between the United States and China will prove harmful to the Midwest region of America, which depends on Chinese imports.

Economics professor Brad DeLong of the University of California-Berkeley notes that there are examples in which protectionism has worked. One example is the protectionism practiced in the 19th century during the Industrial Revolution, which worked because it was part of a “pro-growth or pro-opportunity industrial policy mix” that included “subsidizing railways, schools, banks, and (the right kind of tariffs).” The other example of successful protectionism he presents is that of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China. These nations implemented a “big push” of successful rapid development, and placed tariffs on goods in which they had a comparative advantage.

“All developed countries developed under restrictive policies, and when they got to a stage where their industries produced [more] surplus than was needed by their local markets, that’s when they started preaching [globalization],” said Sifelani Jabangwe, vice president of the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries, arguing that import restrictions have allowed local companies to breathe. “Open markets will not benefit Zimbabwe as it is still growing its industrial capacity, and we are happy the IMF is no longer fighting protectionist policies.”

China, which claims to oppose protectionism yet engages in it with its state-led economy, would be hurt from a tariff war with America, a trading partner accounting for 20 percent of China’s exports. Chinese President Xi Jinping stated that “any attempt to cut off the flow of capital, technologies, products, industries and people between economies, and channel the waters in the ocean back into isolated lakes and creeks is simply not possible. … Pursuing protectionism is like locking oneself in a dark room. While wind and rain may be kept outside, that dark room will also block light and air.” Xi also said at the recent summit of the One Belt, One Road initiative in Beijing that “we need to seek win-win results through greater openness and cooperation, avoid fragmentation, refrain from setting inhibitive thresholds for cooperation or pursuing exclusive arrangements, and reject protectionism.”

ASEAN, the 10-country association of Southeast Asian nations, represents some of the world’s fastest-growing economies due to free, open trade. It opposes protectionism. The group, whose region consists of 650 million people, warns of “uncertainties surrounding global economic recovery, the rising trends of protectionism, and global policy uncertainties.” One of the ASEAN nations, the developmental state of Singapore, developed with an agricultural sector that was geared toward trade protectionism, and an industrial sector that believed in free trade. Singapore’s business leaders were committed to free trade and government action in this developmental state that makes economic growth its top priority and maximizes business opportunity.

Many of the fastest-growing economies in the world are also in Africa, which is making moves toward economic integration of the continent. As these nations emerge as players in the interdependent global economy and position themselves in economic competition with other parts of the world, they must decide what role, if any, protectionism will play in their development.