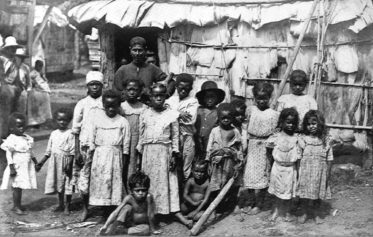

With 18,500 homes destroyed and billions of dollars in damage, the U.S. Virgin Islands have been forgotten, even as America’s neglect of Puerto Rico has drawn media attention. Like Puerto Rico, U.S.V.I. suffers from a long legacy of colonialism and racism from the U.S., with a federal policy treating the inhabitants of nonwhite territories like second-class citizens (Photo: Wikimedia Commons).

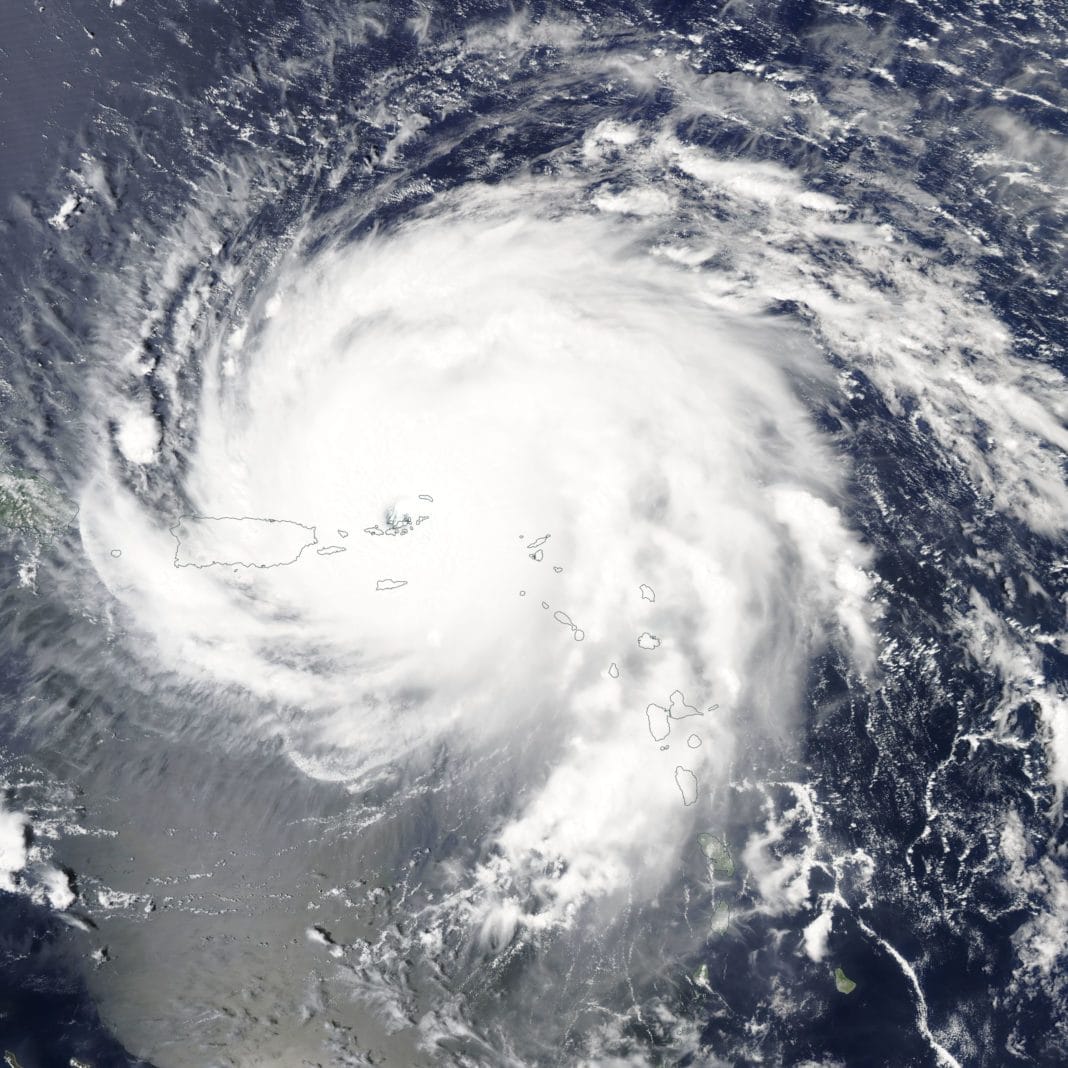

As much of the recent media focus has been on the aftermath of the devastation in Puerto Rico and the estimated more than 4,600 people who died there in the wake of Hurricane Maria, little is said of the U.S. Virgin Islands. Also a territory of the United States, and very much a colony like its Caribbean counterpart, the U.S. Virgin Islands have endured much damage from the dual Category 5 hurricanes Irma and Maria that landed only two weeks apart in September 2017.

As opposed to the relatively quick post-hurricane recovery efforts on the mainland, the Virgin Islands have experienced a slowed recovery due to a shortage of cash in the territory. As the Washington Post reported, contractors who are repairing and rebuilding the storm-damaged homes have not been paid in months. This in a territory that faced financial woes even before the successive hurricanes, with the storms crippling tourism and eroding the tax base. Approximately 18,500 homes were destroyed on the three major islands of St. Thomas, St. Croix and St. John, on which fewer than 100,000 people live.

The federal government has allocated $186 million for the Sheltering and Temporary Essential Power (STEP) program to repair 10,000 damaged homes. While the U.S.V.I. government wants the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) to release the money because it cannot afford to pay the upfront costs to the contractors, FEMA has declined on the grounds that the agency reimburses for costs that state and territorial governments pay upfront under such assistance programs. AECOM, which is the primary contractor repairing homes in the islands, says it has not been paid and therefore is not paying its subcontractors.

The recovery is coming along slower than anticipated, with residents saying they are not ready as the new hurricane season approaches. According to U.S.V.I. Gov. Ken Mapp, recovery will take five to seven years, and the territory is eligible for a little over $8 billion in federal assistance.

According to Genevieve Whitaker — president and cofounder of the Virgin Islands Youth Advocacy Coalition, a civic organization dedicated to civic literacy and decolonization in the Virgin Islands — national news media are paying no attention to the U.S. Virgin Islands. “What’s really going on is … our power issues are resolved. There are times when the power is going in and out and there are outages, St. Johns and St. Thomas more than St. Croix,” Whitaker, a St. Croix native and U.S.V.I. Senate candidate, told Atlanta Black Star. “You fly over the Virgin Islands, you see blue roofs. People were underinsured, people are struggling to have their roofs repaired. A company had a contract to replace roofs and make houses livable. People still have blue roofs,” she said of the temporary roofs placed on residents’ homes. “There is an effort for stronger structures. We have a lot of wood [utility] poles and there is a move for steel poles,” she added of the efforts to fortify the infrastructure.

Whitaker took note of the difficulties people have had dealing with FEMA and the slow process of filing their damage claims and seeking assistance from the federal government. “I didn’t have any insurance; I rented a house,” Whitaker said. In addition, people must prove ownership of their property, sometimes in the family for generations, in terms of title and deed documents. “There are reports of people having deeds that go back to their great-great-grandparents. There are no clear guidelines,” she said, also noting that people were forced into federal disaster loans.

“There are concerns about the governor being too ambitious,” Whitaker added of the financial crisis in the territory, including $2 billion in debt owed to Wall Street bondholders and creditors, which was taken out to fund essential services. Further, the crisis has resulted in $3.4 billion in unfunded public pensions and retiree health care, and a pension fund that is nearly 20 percent unfunded and will run out of money in five years. “Before the storm we were in a severe deficit, and we have an annuity system on the brink of collapse.”

For Whitaker, who has served as a delegate before the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva, and a fellow for the International Decade for People of African Descent (IDPAD), the economic and political situation in which the U.S. Virgin Islands finds itself is steeped in a history of colonialism and racism against people of color. Like Puerto Rico, the predominantly Black territory was acquired by the U.S. during the height of racial segregation and was subjected to second-class citizenship status. “The issue is colonial,” she said. “Any progress we made, we are stymied by the federal government,” Whitaker said, while also acknowledging “we have to give them credit for the help they do give.” Nevertheless, she points to the “lack of a fundamental right to vote,” including a 1901 Supreme Court decision “that calls us savages” and an “alien race.” “Any possessions and lands acquired are uncivilized,” she said, maintaining this unequal treatment persists.

The 1901 Supreme Court decisions in question are the so-called Insular Cases — racist decisions from Justice Henry Brown, the author of the Plessy v. Ferguson racial segregation case — which laid the groundwork for America’s treatment of nonwhite territories. For example, in Downes v. Bidwell, the court wrote that “If the conquered are a fierce, savage, and restless people, he may, according to the degree of their indocility, govern them with a tighter rein so as to curb their ‘impetuosity, and to keep them under subjection.’ Moreover, the rights of conquest may, in certain cases, justify him in imposing a tribute or other burthen, either a compensation for the expenses of the war or as a punishment for the injustice he has suffered from them.” The court also wrote:

“We are also of opinion that the power to acquire territory by treaty implies not only the power to govern such territory, but to prescribe upon what terms the United States will receive its inhabitants, and what their status shall be in what Chief Justice Marshall termed the ‘American empire.’ There seems to be no middle ground between this position and the doctrine that, if their inhabitants do not become, immediately upon annexation, citizens of the United States, their children thereafter born, whether savages or civilized, are such, and entitled to all the rights, privileges and immunities of citizens. If such be their status, the consequences will be extremely serious. Indeed, it is doubtful if Congress would ever assent to the annexation of territory upon the condition that its inhabitants, however foreign they may be to our habits, traditions, and modes of life, shall become at once citizens of the United States.”

The U.S. Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico face the same circumstances as people of color, Whitaker insists, with racial overtones in their relationship with the federal government, even in the tone of the insurance adjusters who came to prove ownership of the damaged property. “It’s the same mentality, we’re both colonial subjects. We’re treated the same,” she said. “This is a racial justice issue.”

What Whitaker wants to see for the U.S.V.I. is what was fought for in the civil rights movement, which is recognizing all people as equal. “We have a 1901 decision that calls us savages, and I would like this overturned. In terms of self-determination, here we are unable to vote for president, we are unable to take part in the elections. We have tried to become a part of CARICOM [The Caribbean Community group of nations], [but] it was denied by the U.S. State Department,” she said of various local efforts that were undermined. “Congress has come after us [in term of] monies to be allocated. It’s just this treatment where they have these programs and they pull the rug,” she said of federal aid to the territory. Further, the U.S.V.I. must collect a 6 percent tariff on all goods imported into the territory, which is remitted to the federal government, demonstrating the colonial nature of the relationship between the U.S. Virgin Islands and the mainland.

Not unlike the process of overcoming a legacy of colonial oppression in which Black people were regarded as savages, the process of recovery in the U.S. Virgin Islands is slow.