The American Civil Liberties Union is suing the U.S. government over what it calls the unlawful separation of a Congolese woman and her 7-year-old daughter who sought asylum after crossing the California-Mexico border. (AP Photo/Elliot Spagat, File)

HOUSTON (AP) — The American Civil Liberties Union accused the U.S. government on Monday of unlawfully separating a Congolese woman and her 7-year-old daughter by holding them in different immigration facilities, two time zones apart, after they sought asylum four months ago.

The ACLU said the family’s case is one example of the practice of President Donald Trump’s administration to target immigrant families who are seeking asylum through processes established under U.S. law.

Trump has not announced a formal policy to hold adult asylum seekers separately from their children, but top administration officials have said they believe the asylum process is overwhelmed and challenged by people making frivolous claims.

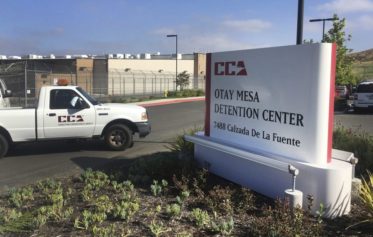

The woman is being held at a detention center in San Diego, while her daughter is being held in a facility for unaccompanied minor children in Chicago, about 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) away.

The mother and daughter entered the U.S. together in California in November and turned themselves into U.S. Customs and Border Protection agents. Initially, the two were kept together. But about five days after they entered the U.S., the child was taken away “screaming and crying, pleading with guards not to take her away from her mother,” according to a lawsuit filed in federal court in San Diego.

The woman and her daughter have spoken around six times by phone since their separation.

The ACLU is asking that the woman and her daughter be released to a shelter that serves asylum seekers from African countries or be placed in a family detention center run by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security declined to comment on the lawsuit.

The U.S. government is bound to release immigrant children from custody if possible and otherwise hold children in the “least restrictive setting” available, according to the 1997 Flores settlement, which ended a long-running lawsuit over the treatment of immigrant children, and later court rulings. The Trump administration has called for ending the Flores settlement as part of its demands for changes to immigration laws.

Lee Gelernt, deputy director of the ACLU’s Immigrants’ Rights Project, said Monday that the woman is from a village in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and speaks little English.

The woman passed the initial screening to determine if she had a “credible fear” of returning to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the lawsuit said. Gelernt declined to name her or discuss her case in detail, saying she could be in danger if she’s ultimately denied asylum and has to return to Congo.

For now, Gelernt said, “she is worried sick about her daughter, whether she’s ever going to see her again.”

Under previous administrations, immigration authorities charged thousands of people with illegally entering or re-entering the U.S., holding them in jail and at times separating them from their children. But Gelernt and other immigrant advocates say the Trump administration is detaining more adults seeking asylum and separating them from their children than in previous years.

Advocates have also accused border agents of unlawfully turning away people who are seeking asylum at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The Trump administration has broadly cracked down on people who cross the U.S.-Mexico border without legal permission. In a January interview with The Associated Press, Tom Homan, acting director of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, said there “have been some separations done,” particularly in cases where parents have been accused of paying smugglers to bring their children across the border.

Homan said he believed many families that seek asylum are making weak claims that are ultimately rejected by immigration judges.

“I’d be a fool to say that none of them have a case of credible fear. They’re really escaping danger,” Homan said. “But I can tell you … many of them are taking advantage of a low threshold.”