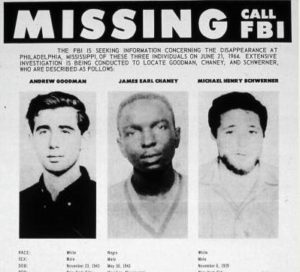

Fifty-two years ago, three young men were killed by KKK members while trying to register Black voters in Mississippi.

During the summer of 1964, hundreds of volunteers descended upon Mississippi to take on the daunting task of registering African-Americans to vote in a state plagued by violent racism.

On June 21, three of those young volunteers disappeared in Neshoba County. James Earl Chaney, Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner had been stopped that evening by a deputy sheriff on their drive back from a recently burned Black church. After an overnight stay in jail, the men were released into the dark. Their bodies were found buried in an earthen dam 44 days later, following weeks of searches by the FBI.

They had been chased, abducted and brutally murdered by KKK members.

Public outcry over the fatal shootings led lawmakers to fast-track the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which, in part, prohibited states from enacting discriminatory voter requirements.

State and local officials declined to pursue charges, claiming there was insufficient evidence. In 1967, a federal grand jury indicted 18 men on charges of conspiracy, though just seven were convicted and received brief sentences of no more than 10 years.

On the 41st anniversary of the crime in 2005, the state of Mississippi convicted Edgar Ray Killen on three counts of manslaughter. He was sentenced to 60 years in prison.

The incident has become known as the Mississippi Burning case, after the 1988 fictional film inspired by the tragedy.

Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood announced Monday investigations by state and federal authorities on the case would end after 52 years.

“The evidence has been degraded by memory over time, and so there are no individuals that are living now that we can make a case on at this point,” Hood said at a news conference. “We have determined that there is no likelihood of any additional convictions. Absent any new information presented to the FBI or my office, this case will be closed.”

The case was recently revisited as part of the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of 2007, which directed the U.S. Department of Justice and FBI to pool their resources toward re-investigating the many unresolved murder cases of the era.

“The Justice Department has investigated this case three times over 50 years and has helped convict nine individuals for their roles in this heinous crime,” Vanita Gupta, head of the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division said in a statement. “Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner gave their lives while struggling to advance the cause of civil rights for all. Though the reinvestigation into their heinous deaths has formally closed, we must all honor their legacy by forging ahead and continuing the fight to ensure that the founding promise of America is true for all of its inhabitants.”

Meanwhile, surviving relatives of the victims continue to live with the horrible events of that night.

“This case will never be closed until it heals the wounds that have divided our country,” David Goodman, younger brother of Andrew, told the Atlantic. “You can’t move past a wound while it’s open, even if you cover it up with a bandage.”

Goodman said he was not surprised by the FBI’s decision.

“Society does not want to try itself, so how do you close a case? It doesn’t make sense in the greater scope of things,” he said.

“Tragically for the people of Mississippi, and for our nation, many murders took place over so many years, in which people of color were targeted, and those who attempted to support them became the victims of brutality as well, all deprived of basic civil rights of citizens,” Schwerner’s widow Rita Bender said, per the Jackson Clarion-Ledger.