For African-Americans, fingerprinting can serve as a double-edged sword. Any efforts that employ fingerprinting as a means of providing security and safety may have good intentions on the surface. However, as the most highly-monitored and punished demographic, Black people are not served well by the practice.

A case in point is the city of Los Angeles, which now requires fingerprinting background checks for those who apply to become Uber or Lyft drivers. As Susan Burton–the founder and executive director of A New Way of Life, a leadership and reentry program for formerly incarcerated women—wrote in the Los Angeles Sentinel, fingerprinting creates inherent risks and dangers for Black people.

Burton argues that for people of color, fingerprinting is neither safe nor simple. “By now it’s been well-documented that fingerprinting discriminates against people of color, who are far more likely to be arrested than their white peers,” she wrote. “Requiring fingerprint-based background checks is not only misguided policy, it’s an economic catastrophe for the very people who need these jobs the most.” Further, as Burton pointed out, with Black unemployment double the national average, fingerprinting background checks create an unnecessary barrier to work, particularly for Black people.

“The problem with fingerprinting background checks is that they cast too wide a net, and sweep up the innocent along with the guilty,” she argues. “One-third of all Americans have been arrested by the time they turn 23. Violent offenses account for only four percent of this total –the majority of arrests are for non-violent drug offenses and a range of ‘other offenses,’ including disorderly conduct, drunkenness, vagrancy, and loitering.” In a nation where Blacks are arrested far more often than whites, Burton notes, it is unfair for people to fail a background check and miss out on an employment opportunity simply because they were arrested but not convicted of a crime. And this applies to people who have paid their debt to society as well.

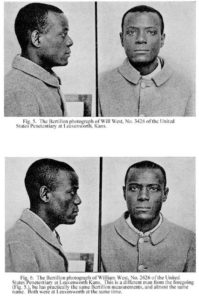

Will West and William West. Graphic by Harris Hawthorne Wilder and Bert Wentworth, “Personal Identification: Methods for the Identification of Individuals, Living or Dead.” Boston: Gorham, 1918, 31.

Fingerprints and Black people have a dubious past that is worth noting here. To sum things up, fingerprinting became a common practice because of the notion that all Black people look alike. As was reported in BlackThen.com, and is documented on the FBI website and in training materials for the Iowa Department of Public Safety, two Black men who looked identical and had nearly the same name were sentenced to Leavenworth Penitentiary in Kansas over a century ago. When Will West entered the prison in 1903, the clerk was confused, believing he had processed the man two years earlier. That man to which he referred, prisoner William West, looked identical to Will West and had the same Bertillon measurements–the standard method of measuring people back then based on key physical features. This helped expose the flaws of the Bertillon method and strengthen the case for the U.S. adopting fingerprinting. “It was this incident that caused the Bertillon system to fall ‘flat on its face,’ as reporter Don Whitehead aptly put it. The next year, Leavenworth abandoned the method and start fingerprinting its inmates. Thus began the first federal fingerprint collection,” according to the FBI says on its website. As the Iowa Department of Public Safety notes, recent opinions suggest the two West men were related.

But as the Telegraph reported in 2014, fingerprints may not be so unique. According to Mike Silverman–the Home Office’s first Forensic Science Regulator in London–human error, partial prints and false positives render fingerprint evidence not nearly as reliable as many people believe.

“Essentially you can’t prove that no two fingerprints are the same. It’s improbable, but so is winning the lottery, and people do that every week,” said Silverman, who introduced the first automated fingerprint detection system to the Metropolitan Police in London. “No two fingerprints are ever exactly alike in every detail, even two impressions recorded immediately after each other from the same finger,” he added, noting that it requires an expert to determine whether a print taken from a crime scene and one taken from a subject came from the same finger.

Meanwhile, as was written in Newsweek in 2015, a report in the American Journal of Physical Anthropology found that a rigorous analysis of one’s fingerprints may provide clues as to that person’s racial ancestry. The research found differences in tiny etchings, known as dermatoglyphics, among African-Americans and European-Americans.

In other words, be careful out there.