Singers perform during the Sapelo Island Cultural Day, held each October on the island. The festival celebrates the songs, stories, dances, and food of the Geechee and Gullah culture, which developed on the Sea Islands among enslaved West Africans between 1750 and 1865. ( Jennifer Cruse Sanders)

Descendants of freed Africans who established a settlement off the coast of Georgia and South Carolina have filed a lawsuit against state and local authorities claiming they have been neglected.

The Gullah-Geechee are descendants of enslaved Africans who formed a separate community on Sapelo Island after they were emancipated. The community was separate from the mainland and the settlers managed to maintain some of their African culture. The term “Gullah” is believed to refer to Angola, a country where some of the original enslaved Africans came from, or Gola, a West African ethnic group. Other scholars say the term comes from the word “Guale,” a Spanish term for a Native American tribe or the Ogeechee River, which comes from a Creek term. The Gullah-Geechee also formed a distinctive English cereole language which includes several terms based on African languages and maintained African customs.

According to The Associated Press, the residents claim they are paying taxes and not getting any local services.The Gullah-Geechee also say that white property developers are flouting zoning laws and building expensive vacation homes on the island, which are pricing them out of the market. These developments are threatening the long-term survival of the community which has existed for more than two centuries.

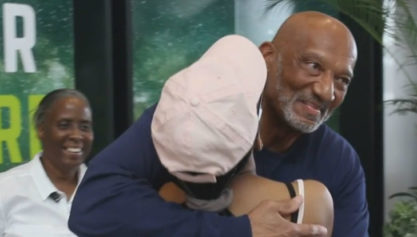

“We’re looking for those protections to say our survival and sustainability is more important than vacation homes and losing the land by measures we consider illegal,” said Reginald Hall, whose said his family’s roots go back 224 years in the community.

“We want to survive on the island,” said Hall, at a press conference outside the federal courthouse in Atlanta. “These are our homes. This is our land.”

The 135-page lawsuit filed lists the state of Georgia, McIntosh County and the Sapelo Island Heritage Authority as defendants.

According to The AP, Reed Colfax, attorney for the Gullah-Geechee descendants, said the county doesn’t maintain the roads, operate a modern sewer system or provide emergency service, despite collecting high taxes. The state also operates a ferry that serves the mainland. But since it runs infrequently, it makes it difficult for working families to live on the island.

Sarah Drayton, 87, is one of the 57 property owners who brought the lawsuit. She said she wants to fight to maintain the community established by her ancestors.

“When I walk some of those roads, I can see and feel my grandparents because they walked those same roads,” she told The AP. “I would like to be able to pass that down to my children and grandchildren.”