But a different type of protest is at the heart of Chi-raq. The film is based on Lysistrata, a Greek comedy written by Aristophanes in 411 BC. Like its namesake, Lysistrata, played by Teyonah Parris, comes up with a last ditch effort to stymie gun violence by convincing women in her community to “deny all rights of access or entrance” and “lock it up” until the gun violence in Chicago subsides. Chi-raq’s trailer has already inspired several women in Chicago to emulate the strategy.

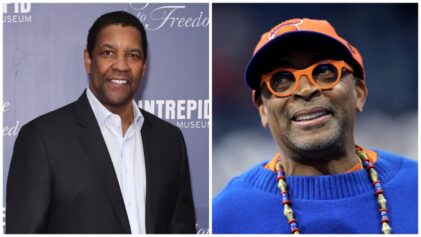

Spike Lee has never been the subtle type. He knows sex is a powerful weapon and can be an effective form of protest. While promoting Chi-raq on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, Spike Lee stated that a sex strike could even be effective in halting sexual assault on college campuses.

“I think a sex strike could really work on college campuses where there’s an abundance of sexual harassment or date rapes,” Lee told Stephen Colbert. “Second semester it’s going to happen. Once people coming back from Christmas and some stuff jumps off, there’s going to be sex strikes in universities and college campuses across this country.”

This statement has come under tons of scrutiny, which to Spike Lee, is like saying water makes someone wet. In his Washington Post interview, Lee talked about the feminist critique he’s facing for Chi-raq.

“This feminist thing. So let me ask a question, are you going to stand behind that feminist stance and say why should we women do it?” he asked. “Or are you going to save your children? As a feminist, you should want, I think correctly, that you should want for murders to stop. As a feminist, you don’t want your daughter, or your son, or any mother to have their children murdered. We get sidetracked into arguments about feminism, or this or that. That’s a distraction.”

Both statements speak to what Lee believes is women’s greatest weapon— it’s the only way to fight back in a way men understand. Chi-raq is Lee’s answer to a woman’s role in times of great violence. Its a male-slanted view toward stopping what men supposedly covet most— sex and power. Violence is a means toward gaining power—guns and warfare acts as a conduit. Sex strikes are not the only way for women to fight back.

Lee cites several modern examples of sex strikes being implemented, including a conflict taking place in the Philippines in 2011, and Leymah Gbowee’s use of it in helping halt the Second Liberian Civil War. However, even Gbowee stated that, “The [sex] strike lasted, on and off, for a few months. It had little or no practical effect, but it was extremely valuable in getting us media attention.”

Media attention is the all important conduit toward ending any war. Gbowee, a peace activist influenced by Dr. Martin Luther King and Gandhi, led the Women of Liberia Mass Action for Peace through acts of civil disobedience, including occupying soccer fields and bombarding peace talks armed only with signs reading, “Butchers and murderers of the Liberian people — STOP!”