In his new book, Jerven argues that economists have fundamentally misunderstood the trajectory of economic growth in Africa because they mistakenly emphasized the poor patterns of growth in the 1970s and 1980s and ignored the incredible growth in African economies that took place in the 1950s and 1960s. While economists focused on “a chronic failure of growth,” Jerven notes that this phenomenon is “something that never actually happened.” Furthermore, many economists treated Africa as more-or-less a coherent whole, looking to explain differences between African states and those elsewhere in the world rather than comparing African states to one another, furthering the narrative that “Africa” wasn’t growing while ignoring relative growth among African states.

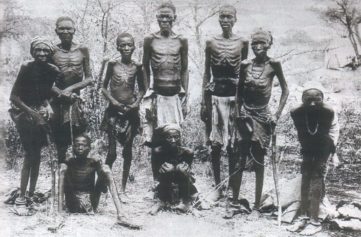

Out of the desire to explain non-growth (even though it was a faulty premise), economists started to focus on income gaps with other parts of the world, which led to studies of other factors that came along with low income. These findings led to neoliberal economic policies mandated by the World Bank and International Monetary Fund in the 1970s and 1980s, which had negative consequences for African economies and people’s livelihoods. In short, poorly done economic research led to devastating policies. Anyone who does policy-relevant research should be particularly concerned about the quality of that research, as it can have real-world implications.

Read more at www.washingtonpost.com