According to The New York Times, a study of the Caddo Parish, Louisiana, court system has revealed prosecutors often exclude Blacks from jury trials so they can tip the scales of justice in their favor. The article, written by Adam Liptak, also said prosecutors preferred to have all-white juries because Black jurors reduced their conviction rate.

“No defendants were acquitted when two or fewer of the dozen jurors were black. When there were at least three black jurors, the acquittal rate was 12 percent,” Liptak said. “With five or more, the rate rose to 19 percent. Defendants in all three groups were overwhelmingly black.”

Lawyers also said prosecutors try to exclude Black people from jury trials because they were less likely to support the death penalty.

“Opposition to the death penalty is much more common among black people, polls regularly show,” said Kent S. Scheidegger, a lawyer with the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation, in an interview with The New York Times. “Striking jurors for hesitation about capital punishment is legitimate, he continued, adding that it is largely balanced ‘by defense lawyers doing exactly the same thing the other way.’”

According to Slate, a Pew Research poll showed 63 percent of whites supported the death penalty, while only 36 percent of Black people were in favor. It seems Black people were less likely to support the death penalty because, having seen so many Black men freed from death row, they realize how flawed the system is.

The study also revealed stark disparities in the Caddo Parish criminal justice system. According to The New York Times, about half of the residents of Caddo Parish are Black, but Black people made up 83 percent of the defendants in the study.

The New York Times article pointed out that prosecutors often used “peremptory challenges,” which allow potential jurors to be dismissed with no explanation, to eliminate Black residents. However, the Supreme Court has ruled that if lawyers are accused of racial discrimination, they have to provide a neutral justification. Liptak said lawyers offered a broad range of reasons to cut Black jurors.

“Here are some reasons prosecutors have offered for excluding blacks from juries: They were young or old, single or divorced, religious or not, failed to make eye contact, lived in a poor part of town, had served in the military, had a hyphenated last name, displayed bad posture, were sullen, disrespectful or talkative, had long hair, wore a beard,” Liptak said.

The New York Times article also said some prosecutors clearly stated they didn’t want any Black citizens on the jury.

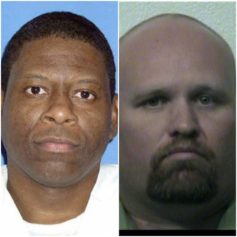

“The case arose from the 1987 trial of Timothy T. Foster, an African-American facing the death penalty for killing a white woman, Queen Madge White. Prosecutors worked hard to exclude blacks from the jury,” said The New York Times. “In notes that did not surface until decades later, they marked the names of black prospective jurors with a B. They highlighted those names in green. They circled the word ‘black’ where potential jurors had noted their race on questionnaires.”

This issue is not unique to Louisiana. The New York Times said similar problems had also been found in other parts of the country.

“That is consistent with patterns researchers found earlier in Alabama, Louisiana and North Carolina, where prosecutors struck black jurors at double or triple the rates of others,” said The New York Times. “In Georgia, prosecutors excluded every black prospective juror in a death penalty case against a black defendant, which the Supreme Court has agreed to review this fall.”

Scholars say racially biased jury trials undermine the integrity of the legal system.

“If you repeatedly see all-white juries convict African-Americans, what does that do to public confidence in the criminal justice system?” said Elisabeth A. Semel, the director of the death penalty clinic at the law school at the University of California, Berkeley.

Although many Americans see jury duty as an annoyance, many of the Black people interviewed in The New York Times article saw it as an important civic duty.

“Next to voting, participating in a jury is perhaps the most important civil right,” said Ursula Noye, a researcher who compiled the data for the report.