To no one’s surprise, an industry helping to perpetuate whiteness as a global beauty “ideal” struck the hearts of Black women yet again earlier this week.

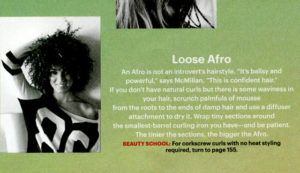

Allure magazine, beauty bible of white women everywhere, featured a white model sporting a faux-Afro for its August issue. The title of the hotly debated article “You (Yes, You) Can Have an Afro*” included a tutorial on how straight-haired women could acquire “rag-curls.”

The Internet drew in a multitude of women who expressed their thought on whether Allure’s spread was offensive. Most labeled it another depiction of cultural appropriation. Some called the story a form of flattery.

Essence took a poll on the matter and 35 percent of voters agreed “whatever they (white women) do it’s not an Afro.”

To understand fully, it has to be said it’s not just hair and it’s not about exclusion. Black women who wear their natural hair are not rocking it for a trend. Hair is an integral part of a woman’s confidence; it is partly why bad hair days require hats and why good hair days require selfies. Historically, Black women were told their hair was a problem that needed to be hidden or altered.

Black women did not ask to have the Eurocentric standard of straight blond hair and blue eyes shoved down their throats. It was held over their heads as so unachievable they resorted to chemically destroying their natural curls to adapt to a form of beauty society told them was acceptable. The idea to straighten their hair came out of a need to survive not a desire to be trendy. Today, a Black woman wearing her natural hair abandons the deeply ingrained frame of thought that white hair is the only beautiful texture in existence.

Women who wear their natural Afros, locs or curls are viewed as professional liabilities in the workforce and academia. Even the military recently passed a ban on Black women wearing braids or locs. Black hair is not accepted in this society. Women are passed over in preference for a Black woman who wears her hair closer to the white vision of beauty. In preparation for job interviews, some will straighten or comb their hair into styles that mask their true nature. In reality, Black women have been told to hide their Afros to make it in a white world.

Simply put, a white woman can wash out her temporary Afro; a Black woman can never wash out her Blackness.

Allure released a statement on the matter: “The Afro has a rich and aesthetic history. In this story, we show women using different hairstyles as individual expressions of style. Using beauty and hair as a form of self-expression is a mirror of what’s happening in our country today. The creativity is limitless – and pretty wonderful.”

While the magazine claims it is a form of self-expression, it is not the natural self. That is the subtext behind the recent natural hair movement. Black women are choosing to celebrate who they are, how they are. Instead of burning their scalp or breaking their accounts to achieve a look that isn’t natural to them, Black women are reclaiming their version of beauty along with their self-confidence.

Interestingly enough, Allure fails to even mention the Afro’s “rich and aesthetic history.” So yes, it is a mirror for what is happening in this country, an appropriation of Black culture. It happens everywhere nowadays.

Remember during the Oscars when Giuliana Ranic of E! News said Zendaya Coleman’s faux locs “looked like they smell like patchouli oil or weed?” The proof of cultural appropriation is directly linked to the shaming of Black women wearing their natural hair.

It is these same critics of Black women who regard Marc Jacobs as creative for thinking he invented Bantu knots by calling them “mini buns,” or refer to Katy Perry’s “baby hairs” as “this year’s newest trend.”

At the end of the day, white women who attempt these corkscrew curls (because as one blogger pointed out, that model was not rocking an Afro) are able to experiment with Black culture on the fence of white privilege then return to society’s beauty “ideal.” All the while ignoring the beautiful history as well as the years of struggle Black women faced to merely wear their hair the way it grows.