While the South is covered with Civil War plaques seemingly on every other corner celebrating bloody battles, there’s virtually no public recognition that Reconstruction even existed—no plaques, no National Park Service sites, no acknowledgement.

But the National Park Service is trying to change that. Over the next year, the park service will ask historians, its own staff members, state historical societies, and the general public about the best sites and methods to capture Reconstruction’s history, according to Gregory P. Downs, an associate professor of history at City College and the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and the author of After Appomattox: Military Occupation and the Ends of War, and Kate Masur, an associate professor of history at Northwestern University and the author of An Example for All the Land: Emancipation and the Struggle Over Equality in Washington, D.C.

Downs and Masur wrote a piece on The Atlantic website revealing that they will be assisting the park service in determining how best to commemorate Reconstruction. The park service has also commissioned a handbook on Reconstruction that will soon be available in parks.

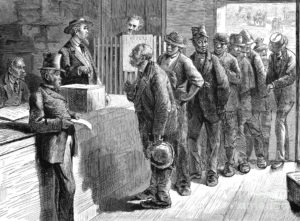

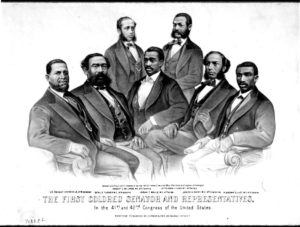

After Emancipation, the United States did extend the vote to Black men, and consequently in the South Black men were elected to Congress, state legislatures, and crucial local offices such as sheriffs and assessors. With the influence of these newly enfranchised Black people, new state governments created public schools and hospitals, and Black people and their white allies founded colleges, churches, and benevolent organizations, according to Downs and Masur.

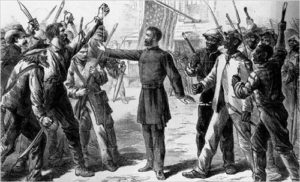

But horror and bloodshed for the Black community soon followed, as white Southerners lashed out violently in bloody campaigns of terror, preventing African Americans from voting, killing thousands of freedpeople and raping untold numbers of Black women, all to reestablish control. By the end of the century, Jim Crow was in place and the Supreme Court in 1896’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision ruled that Black men didn’t have any rights a white man was bound to respect.

Throughout the early 20th century, as recounted by Downs and Masur, historians pressed the case that Reconstruction had been a disastrous mistake and created clearcut villains in the cartoonish Black Southerners holding offices they didn’t deserve, corrupt white Northern carpetbaggers moving south to take what didn’t belong to them, and tyrannical Republican politicians who oversaw an era of unjust, unconstitutional federal intervention. Altogether, this rewriting of history was used as a justification for the horrific racist policies of Jim Crow.

“Against claims that African Americans emerged from slavery unprepared to live independently, historians have unearthed the wealth of institutions and cultural resources that people of African descent developed in slavery and cultivated after emancipation,” Downs and Masur wrote.

But the period still hasn’t gotten its proper due. The Parks Service is attempting to change that. Downs and Masur point out that the agency of late has been willing to tackle sensitive subjects, developing sites commemorating Japanese Internment during World War II, and the massacre of hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho people at Sand Creek by Coloradans enrolled in the U.S. Army, in addition to Civil War memorials that now include the roles of Black soldiers, slaves, and freedpeople.

“Identifying those sites and creating a framework for public engagement with Reconstruction cannot smooth out the complexity and travails of the era,” Downs and Masur wrote, “but it can be a part of fulfilling the Park Service’s mission of helping Americans grapple with this nation’s history, a challenge that in the end means not just celebrating its victories but also remembering its tragedies and asking serious questions about defeats and wrong turns.”