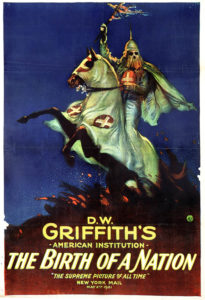

All around us we still see the legacy of D.W. Griffith’s epic and profoundly racist tale. It led to the creation of rating codes for motion pictures. It caused Hollywood to run away from casting Black people in movies for many decades. It led to a huge spike in membership for the Ku Klux Klan. It led to the rapid growth of the fledgling NAACP. And perhaps most importantly of all, it hatched the protest movements and tactics that would bear fruit a generation later in the Civil Rights Movement.

At the same time, it was the most horrific and most influential movie in the history of American cinema.

The movie’s impact is explored in a piece on Slate.com by Dorian Lynskey, who writes that the film was “hated like no picture before or since for its grotesque distortion of Reconstruction, in which Black characters are sexual predators and vengeful thugs, former slave owners are persecuted victims, and members of the Ku Klux Klan are gallant saviors.”

The movie was so popular among white audiences that by the end of 1917 it had grossed the astronomical sum of $60 million, which in 2015 is the equivalent of well over a billion dollars.

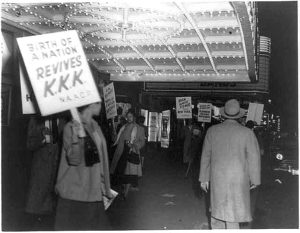

The movie created a real dilemma for Black activists like W.E.B. DuBois and the white liberals who were in charge of the NAACP. They needed to stop the spread of the film, but they didn’t want to come out in favor of censorship and a denial of free speech rights. However, they were willing to grant that the case of Birth was so extreme that they were willing to seek a ban.

“The Birth of a Nation didn’t just transform cinema forever; it inaugurated a debate about art, race, and freedom of expression that shaped American history,” Lynskey writes.

Clearly the ban didn’t happen.

Thomas Dixon Jr., the writer of the play The Clansmen, on which the movie was based, hoped that his work would lead to the massive passage of legislation banning interracial marriage. While that didn’t happen, Lynskey points out that the film did stoke white racial hatred to manifest itself in the increased murders of Black people.

DuBois wrote in the Crisis, the NAACP journal that he ran, that the number of lynchings in America rose sharply in 1915, no doubt attributable to the film. It wasn’t even difficult to connect the two: In Lafayette, Indiana, a white man walked out of a screening of the movie and shot dead a 15-year-old Black high school student.

Inspired by Birth, an Alabama teacher named William J. Simmons relaunched the KKK, using a still from the movie of a horseman with a burning cross as the new Klan’s logo. In fact, his new Klan made its first public appearance outside the Atlanta premiere of the film. In addition, the film’s publicists sold Klan merchandise such as hats and aprons and even hired hooded horsemen to promote screenings.

Black people also went to theaters (segregated ones) to view the film—and were traumatized by the experience. Black actor William Walker, who would later appear in the film To Kill a Mockingbird, described an audience full of Black people crying and cursing.

“You had the worst feeling in the world,” he said in a 1993 documentary, D.W. Griffith: Father of Film. “You just felt like you were not counted. You were out of existence.”

After the film, not only did Hollywood shy away from using Black actors, Lynskey writes, but the new movie codes actually prohibited movies from showing any portrayal of interracial relationships—giving the writer, Dixon, at least a portion of what he wanted.

“The NAACP established a strong national network, pioneered direct-action tactics that would bear fruit in the civil rights movement, and emboldened black activists to make other demands,” Lynskey writes. “It galvanized anti-racists, shone a light on race relations in every city that considered whether a movie could trigger a riot, and forced even publications that abhorred censorship to decry the movie, often for the first time…In failing to silence the movie, the protesters gave themselves a megaphone and made a mighty noise. In losing the first battle against Birth and its toxic version of American history, they won the war.”