The lack of Black men’s college basketball coaches is not just noticeably missing from the Final Four—they are missing all across the country. Once a powerful source of leadership in the NCAA, the presence of African-American men coaching African-American young men at major colleges is fading like the markings on the bottom of an old pair of sneakers.

Since the end of the college basketball’s regular season, seven Black coaches have been fired—at George Mason, Penn, Holy Cross, Mississippi State, Alabama, DePaul and Nevada.

Three hires have been made as replacements. . . none Black.

St. John’s and Texas now have openings, too. Chris Mullin, the former St. John’s great, already reportedly is mulling that job. Nowhere are African-American coaches being listed, at least publicly, as candidates for these openings. Of about 330 Division I head-coaching jobs, Blacks coaches make up about 17 percent of those positions—the lowest percentage in 20 years. Meanwhile, African-Americans constitute about 60 percent of players.

This is a problem, a shame on the sport.

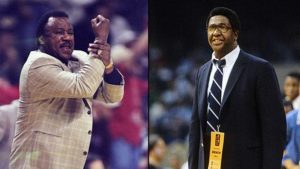

Gone are the strong, convicted voices of the past: coaches John Thompson (Georgetown), John Chaney (Temple), Nolan Richardson (Arkansas) and George Raveling (USC). Left are competent Black coaches who are less imposing and more restrained, virtual figureheads more concerned about keeping their jobs than adding more jobs for men who look like them.

Long gone are Clarence (Big House) Gaines at Winston Salem and John McClendon, after years at HBCUs, who became the first Black coach at a Division 1 school when he went to Cleveland State in 1966. They inspired.

To be fair, the few Black coaches today likely care that their Black contemporaries are outsiders looking in. But they have not been able to do anything about it—or tried much. The Black Coaches Association at one time brought a measure of influence—primarily because championship coaches Thompson and Richardson and smart and steadfast Chaney and Raveling were more Civil Rights movement than politically correct.

Today, the BCA hardly exists. It’s long-time executive director, Floyd Keith, resigned the position in 2013. Since then, sadly, it has been dormant.

Meanwhile, the business it should be tending to goes undone. Last year, Kevin Ollie coached UConn to the NCAA Tournament championship, an impressive feat in his second year as head coach. Ollie, who is Black, told the New York Times that African-American coaches lack the structure and leadership of two decades ago with Thompson, Richardson, et al.

“They paved the way for me that I can have a job and do it successfully,” Ollie said. “But it’s definitely something we need to take a long look at, and hopefully we can get more African-Americans in these jobs, in these positions, that they can run a program.”

Thompson, Richardson, Ollie and Tubby Smith are the only Black coaches to win the NCCA Tournament championship. Chaney, Hewitt, for two, took teams to the Final Four, Hewitt to the title game with Georgia Tech in 2004. So the barrier of a Black coach’s competence has long been shattered.

Richard Lapchick of Central Florida University, who has researched diversity in sports for 50 years, suggested the NCAA adopt a version of the NFL’s Rooney rule, which requires teams to interview Black candidates before making a hire.

“Anywhere that’s been put in place, it has made things better because it just opens the hiring process,” Lapchick said to ESPN. “You’re gonna get bogus interviews for sure, but more than likely the case is going to be even if you had no intentions of hiring that person, if they come in and they’re impressive, which happens consistently in the NFL, people in the organization … they’ll remember that person.”

Good luck on the NCAA taking up such an edict. Meanwhile, colleges have taken on a modern day good ole boy network: search firms.

To avoid the scrutiny of not hiring Black coaches, they pay search firms hundreds of thousands of dollars to execute the search for them. Problem is, the firms are just an extension of a network of white athletic directors who make up 80 percent of those jobs.

Black coaches are not even a part of the firm’s clients, so they sit back and watch, helplessly, as whites who are clients of the firms continually get jobs.

Used to be that Black parents wanted a Black coach as an authority figure to look after their son. You can bet Patrick Ewing chose Georgetown because Thompson was the coach. Raveling, Chaney and Richardson also landed top prospects because of their convictions and the trust that they would be fair and honest with their players and teach them about more than the game.

That factor seems to be less of a recruiting value now. Parents are younger and farther away from the Civil Rights movement and are enthralled by the glamour of the big-name coaches and NBA chances, while giving the coach’s personal, political and social background less credence. Thompson—who walked off the court before a game to protest an N.C.A.A. rule that linked eligibility to standardized test scores, which he viewed as racist—Raveling, Chaney and Richardson were consistently vocal about injustice based on race, and that conviction resonated with parents.

“I was a kid in the ’80s,” VCU coach Shaka Smart told Yahoo! Sports last year, “but I remember the notion that if you were a high-level player from a family that really valued a Black identity, going to play for John Thompson was the thing to do.”

That does not seem to be the case much these days. And colleges, with no one holding them accountable for their lopsided hiring practices, are doing what they always have—selecting candidates that look like them.

And so, as the Final Four commences in Indianapolis this week, Black coaches will be there looking for jobs more than to watch the action on the court.