The United States has erected countless museums and memorials without ever creating a space dedicated to the atrocities of slavery that remain at the very foundation of America.

While federal funding was relatively easy to obtain in order to bring projects memorializing the Holocaust to fruition, the same can’t be said about multiple attempts to create a museum that would bring some attention back to America’s own dark past.

That was the unusual and unfathomable reality that drove John Cummings to spend 15 years and more than $8 million of his own money in order to make the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana more than just a historical relic.

In the town of Wallace, roughly 35 miles west of New Orleans, the Whitney Plantation received a warm welcoming as it opened its doors to the public on Dec. 7, The New York Times reported.

The plantation has not only been restored, but the property has been transformed into a space that is both architecturally stunning and of vast educational importance.

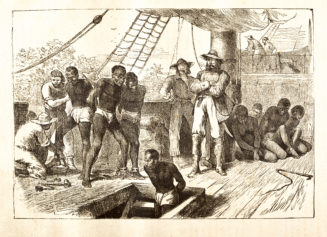

An exhibit on the North American slave trade has been added to the property and rests inside the new visitor’s center.

Just outside, however, history remains intact.

Seven cabins that once served as homes for the enslaved Black people are still standing along a dusty path and the massive iron kettles that were once used to boil sugar cane give visitors a glimpse into the labor intensive days that enslaved people spent on the property.

Even a jail that was used in the past to punish enslaved people was restored and now stands as a symbol of the fact that slavery was about more than grueling hours on a plantation.

It reminds visitors of the sheer depths of slavery that involve inhumane treatment and deplorable living conditions that physically and emotionally tormented generation after generation of enslaved Black people.

This plantation turned museum is one of the only projects dedicated solely to forcing America to confront the vile, twisted history that allowed it to become one of the most prosperous economic powers in the world.

The project itself has a visual appeal that has been praised by architects, and the elements of American history and slavery that have been captured left historians in awe as they made their way through the grounds.

What was the most stunning surprise, however, came in the form of an older white gentleman who was responsible for bringing the project to life.

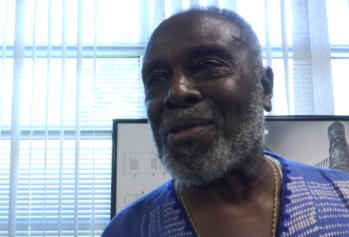

John Cummings (right), the Whitney Plantation’s owner, and Ibrahima Seck, its director of research, in the Baptist church on the grounds. Credit Mark Peckmezian for The New York Times

“Like everyone else, you’re probably wondering what the rich white boy has been up to out here,” John Cummings said as he addressed the crowd that attended the museum’s opening, according to The New York Times.

It’s indeed an unusual story, but Cummings insists the explanation behind him building America’s first museum dedicated to slavery is simple.

“I suppose it is a suspicious thing, what I’ve gone and done with the joint,” he added, addressing his decision to “spend millions I have no interest in getting back” to create the museum and restore the plantation. “I’ve been asked all the questions. About white guilt this and that. About the honky trying to profit off slavery. But here’s the thing: Don’t you think the story of slavery is important?”

He paused for the crowd to answer before he continued on.

“Well, I checked into it, and I heard you weren’t telling it,” he added. “So I figured I might as well get started.”

And so he did.

But there was a moment when his own plans for the property would have been squandered at the hands of corporate greed.

A plastics and petrochemical company called Formosa was the previous owner of the property and had very different plans for it.

Formosa planned to build a $700 million plant for manufacturing rayon back in 1991.

The plans were brought to a halt, however, when preservationists and environmentalists refused to let the project move forward.

Once rayon went out of style, Formosa lost interest in the project and put the property back up on the market.

That’s when Cummings seized the opportunity to create America’s first slavery museum.

While other museums in the country feature civil rights leaders and dedicate small portions of the exhibits to slavery, this will be the first property specifically tailored toward bringing America’s history of slavery to light in a way that the general public can experience.

Ever since embarking on the massive project, Cummings had surrounded himself in literature about slavery’s history so he could become even more educated on the subject matter he hoped to teach others about.

He is also refusing to let accusations of “white guilt” deter him from his work.

All throughout the property there are monuments, beautifully crafted sculptures and other features that Cummings also funded through his wealth.

Many of them are visually appealing pieces with emotionally charged messages, including a sculpture of a Black angel embracing a dead infant.

Others are unconventional ways to highlight the bloody stains of slavery.

Cummings says families will have the option to bypass a memorial in the works that would honor the victims of the German Coast Uprising.

It’s an event that is rarely discussed in American history, New York Times writer David Amsden explains.

“In January 1811, at least 125 slaves walked off their plantations and, dressed in makeshift military garb, began marching in revolt along River Road toward New Orleans,” Amsden reported. “The area was then called the German Coast for the high number of German immigrants, like the Haydels. The slaves were suppressed by militias after two days, with about 95 killed, some during fighting and some after the show trials that followed.”

Cummings’ monument would replicate the decapitated heads that were placed on stakes along River Road to deter other enslaved Black people from revolting.

“It’ll be optional, OK? Not for the kids,” Cummings added.

As his project grew in effort and size over the years, he brought on a Senegalese scholar by the name of Ibrahima Seck in 2012 to serve as the director of the Whitney Plantation.

Seck, 54, serves as the more rational side of the balanced partnership who is frequently engulfed in research while Cummings continues to follow his instinctive nature and make massive spur-of-the-moment purchases that he believes could be connected to the history of slavery in America.

One of those purchases includes an old Baptist church in a neighboring parish that was previously owned by freed enslaved people back in 1867. Cummings paid to have the property moved across the Mississippi so he could restore it.

The project cost him more than $300,000.

For those who have questioned his decision to dedicate the massive amounts of money, land and resources to a more “disturbing” part of America’s history, Cummings believes it’s the only logical approach to the situation.

“It is disturbing,” he said of the decapitated head memorial that is near completion and the other remnants of a dark past that fill the property. “But you know what else is? It happened. It happened right here on this road.”