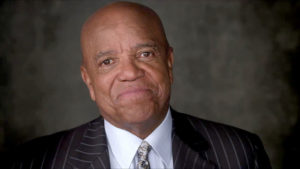

When Gordy was still a young boy, he realized that racial bias and the fear of Black men was so strong in American culture that it could leave even the best product or business struggling to stay afloat.

It’s perhaps one of the most important lessons Gordy used to make a triumphant entrance into the music business.

A young Gordy managed to make money by selling The Michigan Chronicle in Black neighborhoods.

The newspaper was a weekly Black publication in Detroit, and people in his community would eagerly be looking for the young boy so they could snatch up their own copy.

After some time, Gordy realized that there were many untapped opportunities lying outside his own familiar stomping grounds. He realized he could make even more money by selling to white customers as well.

“I said, ‘Well, I’ve sold as many Black papers as I can and I’m the number-one seller here,’” he said during his episode of Oprah’s Master Class. “‘I’m going to take these Black papers into a white neighborhood. Because people are the same!’ ”

Gordy’s reasoning was absolutely right.

White consumers were just as interested in what had been deemed a paper for Black readers, and they were more than willing to purchase papers from him.

“I sold more papers than I had ever sold before. I mean, it was incredible,” he said.

He discovered that Black people and white people shared common interests. What he didn’t realize, not yet anyway, was that racial bias and stereotypes would still be enough to keep his white buyers from purchasing his papers in the future.

Gordy explains that the next time he visited the white neighborhoods, he brought his brother along with him.

That’s when their perception of him as a newspaper salesman changed.

Now he was far from an entrepreneur, he was a “threat.”

“We sold no papers,” he said. “I realized then that one Black kid was cute. Two were a threat to the neighborhood. No one spoke to us! I mean, it’s like they saw us coming and they just moved out the way.”

For some people, that may have been just another childhood experience that would eventually trickle away and end up as nothing more than a distant memory.

For Gordy, it drove his business decisions later in life.

He understood that white and Black people shared common interests. He knew he had discovered the type of artists that people of all colors would enjoy.

Racism trumped any idea of shared interests or universal languages.

“My first few albums, I didn’t put Black faces on them,” he said.

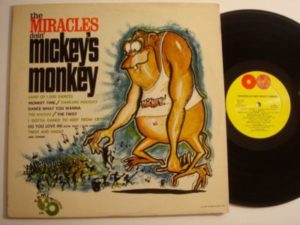

As he names some of his first albums, including “Mickey’s Monkey” by the Miracles and “This Old Heart of Mine” by the Isley Brothers, he pointed out that none of these albums had Black people on them.

Instead, one featured a cartoonish image of a giant ape while the other had a photograph of a white couple on the beach.

“They were all hit albums,” he says.

People of all races could love this music—as long as it was presented to them in a non-threatening way. This philosophy made him a lot of money, though it did earn him criticism in the Black community—even from his own artists—particularly as Black people were persistently pushing for more social and economic equality.

But Gordy still wanted to see past the upheaval, to the good feelings his music could bring to people of all races—even if it does make him sound like a somewhat naive pollyanna.

“That was a very good lesson learned,” Gordy adds. “It made me realize that all people are full of love. All people are beautiful. The difference between us is so much less than the sameness.”