ABS Exalts Black History: Part I

When we contemplate our history, for too many of us our vision is stunted by the wages of oppression. We can’t see the vastness of the treasures that lead from abundant empires directly to our doorstep because we have been affixed with the blinders of racism and white supremacy, which distort and destroy everything they touch. So at Atlanta Blackstar our mission for the 2015 edition of Black History Month is to tear away the blinders and revel in the glory of our people, diving into the ancient civilizations that birthed us, bathing in the wonders that sprouted on the shores of the Nile, in the brilliance that grew out of the Congo.

We asked a team of talented writers and scholars to mimic the dance of the Sankofa bird and carry us back to our roots so that we may move forward. We will be presenting their efforts throughout the rest of February in an impressive array of pieces that reveal to us from whence we came and where we might want to go. There is nothing quite so edifying and necessary as African history, for its grandeur is spectacular in direct proportion to the depths of scarcity we were trained to believe in the New World. It is as essential to us as the air we breathe. We asked our writers to use as a template the words of Langston Hughes, who penned “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” as a 17-year-old boy crossing the Mississippi. Hughes uses the metaphor of the river as a way to trace the splendor of African people. Here at Atlanta Blackstar, we see these as words to live by:

I’ve known rivers:

I’ve known rivers ancient as the world and older than the

flow of human blood in human veins.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young.

I built my hut near the Congo and it lulled me to sleep.

I looked upon the Nile and raised the pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when Abe Lincoln

went down to New Orleans, and I’ve seen its muddy

bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

I’ve known rivers:

Ancient, dusky rivers.

My soul has grown deep like the rivers.

The ‘Gifts the Ancestors Gave’: From Africa to the Delta

By Leonore Tucker

Far too often, the Black history timeline is set for us beginning in 1619, yet the Mississippi Delta bespeaks an accomplished past that began in Africa and continued into the Americas. This February, let’s reaffirm a Black history that started long before the first African slave was born on American soil. This month “let’s take it way back.” In the spirit of the Sankofa bird, let us look back and discover our history. It is ours to claim. Let’s “reach back and get it” so we can move forward.

Each year I attend Dance Africa at BAM in Brooklyn, New York. Before the sounding of drums that revive our African Diasporic heartbeat, the audience is initiated for the performances by listening as Baba Charles Chuck Davis, the event’s director, MC and founder, recites the words of the poem “Spirits” by Birago Diop, the Senegalese poet.

“Listen to Things more often than Beings,

Hear the voice of fire, Hear the voice of water. Listen in the wind, to the bush that is sobbing: This is the ancestors, breathing.”

If we listen, we’ll hear rhythms of Africa that sailed to the Delta to be danced to in New Orleans’ Congo Square. If we listen, we hear the voice of the fire as evidenced in the Delta blacksmiths’ artistry on an iron fence in New Orleans, where the Sankofa symbol is welded, linking us to the great bronze sculptors from the kingdoms of West Africa. When we listen to the wind, we know that the seeds of the Harlem Renaissance and great writers like Mississippi native Richard Wright started long ago in Mali with the epic of the Sundiata long before we spoke English. Can the church say Amen? Yes, it can, because it started with the call-and-response tradition of the griots of Africa.

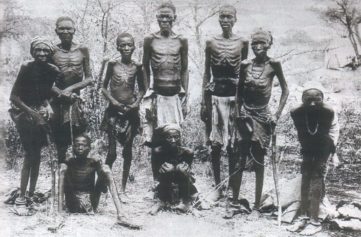

I choose not to think of my ancestors as powerless chattel in the dark bowels of a slave ship. My ancestors’ identity didn’t begin after being sold by slave traders no more than European Jews began with the images we see of them in concentration camps. I choose to remember a complete history.

Luckily, there are things, pieces of evidence of our great past that have been discovered and studied so we don’t have to look far to access them. All we need to do is push a button on a keyboard and we can travel back in time with more information than the mind can handle at once. The Metropolitan Museum of Art has a complete time line of African art starting from 800 A.D. If one wants to view it, there are any number of retellings of the history of Sundiata Keita, the great Malian King, online. I remember sitting entranced during a long hair-braiding session once and viewing a modern adaptation of this epic on DVD.

West Africans were renowned for their bronze, iron and terracotta sculpting as well as weaving. They used methods and techniques that were not known by their European contemporaries, such as lost-wax casting. Their sculptures have been described by critics as possessing “more humanity; more individuality” and being more “refined and naturalistic sculpture.”

The European artists Picasso, Matisse, Modigliani and Brancusi were all influenced by African art, so is there any wonder that we would see its influence in the Delta?

Some famous West African art pieces are the “Head of the King of IFE”; “The Nok Terracottas”; “Girdle,” (12th century; Tellem); “Head,” (12th–15th century Nigeria, Esie) and “Mother and Child,” (15th–20th century). The “Queen Mother Pendant Mask: Iyoba,” (16th century; Nigeria; Edo people, court of Benin) depicts a royal woman who was an adviser to the throne in Benin.

The medieval African woman with her thick beautiful braids sculpted from soapstone in the Head from Nigeria, Esie, resembles gifted diva songstresses Mahalia Jackson and Leontyne Price.

The strength, beauty, leadership and wisdom portrayed in The Queen Mother Pendant Masks recall that of Delta Queens: Ida B. Wells, Fannie Lou Hamer, Myrlie Evers-Williams and Oprah Winfrey.

From the hands of the Tellem people who crafted the “Girdle” in the 12th century descended the hands of Delta quilt makers and ultimately the masterful Northern United States artist Faith Ringgold. One day I learned a valuable lesson from Ms. Ringgold. She had come into a store that I worked in and I quickly waited on her so that I could service the next person. Almost immediately, I realized the greatness of the person who had been in front of me. I felt so ashamed that I had rushed her along without first acknowledging who she was and thanking her for her contributions to my life. When I look back, I realized that I had profiled Ms. Ringgold as a mere senior citizen with long locked white hair. In this same way in the past, when many Europeans came upon art from West Africa, some assumed it was impossible for it to be Africans because of its complexity of craftsmanship. I will always take this lesson with me: Never judge a book by its cover. We of the African Diaspora carry the DNA of those who designed and built the kingdoms of Mali and Benin. People traveled from around the world to get to the great library of Timbuktu that our ancestors created.

In so many ways, the seeds of the ancestors planted in the new world have achieved greatness today, and there is an unquestionable connection between the Delta and Africa. It’s manifested in jazz and blues. A short list of Delta musicians includes: The Marsalis family, Howlin’ Wolf, B.B. King, Jelly Roll Morton, Ruby Elzy, Muddy Waters, Louis Armstrong, Robert Johnson, Bessie Smith and Cassandra Wilson.

A few past literary gems from the Delta are Margaret Walker and Etheridge Knight. Contemporary writers include Mildred Taylor (“Roll of Thunder Hear My Cry”), the writer-scholar Lerone Bennett Jr. (“Before the Mayflower”) and Ann Taylor (“Coming of Age in Mississippi”).

Contemplation of the West Africa-Delta connection inspired poet Langston Hughes to pen the celebrated poem “Negro Speaks of Rivers.”

When we look back to explore our African history and reaffirm the truth about the greatness from which we came, it frees us to reach our true potential without feeling a need to embrace tired ignorant stereotypes of ourselves as a people. We know that although we may have arrived in the Americas in chains and shackles, we already held within our very DNA the knowledge and the power with which in time we would weld those shackles and sculpt them into our own reality.

As we look back in the spirit of the Sankofa, we may have to give ourselves permission to “reach back and take it.” We may feel that African achievements do not belong to us since, after all, we were sold away from Africa, but like Sundiata, the King of Mali, we must accept that this greatness is our inheritance. Perhaps we must also forgive and reconcile with Mother Africa for sending us far away from her across the ocean.

This February perhaps we can begin with the words of the Rachelle Farrell song “Forgive You”:

“I just wanna be whole again I want to be free again. Want to be me again. I just want to heal”

“I forgive you totally completely now what a feeling just releasing from my heart from my mind and soul!”

Then as sister-mother Nikki Giovanni says in “Ego-Tripping”:

We “can fly like a bird in the sky.”

Leonore Tucker is a poet/writer. She studied literature and writing at New School University. She lives in New York but has deep Southern roots.