Over the past year, something truly groundbreaking happened in the U.S., the most prolific jailer in the world: The federal prison population actually went down.

Speaking at a conference at New York University, U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder announced the remarkable phenomenon, which means the prison population is finally mirroring the trends in the crime rate, which has been dropping for decades while the incarceration rate continued to climb.

The federal prison population dropped in the last year by roughly 4,800, according to figures released by Holder’s Justice Department — the first time in 34 years the number of inmates has gone down.

In addition, the number of inmates is projected to drop by more than 2,000 inmates next year and nearly 10,000 the following year, according to internal figures from the Bureau of Prisons.

During his speech, Holder also made reference to the outrage in Ferguson, Missouri, after the police killed unarmed teen Michael Brown last month. While noting that as a former U.S. attorney and the brother of a long-serving police officer he will always have the utmost respect and support for the men and women in law enforcement, Holder said that as an African-American man “who has been stopped and searched by police in situations where such action was not warranted, I also carry with me the mistrust that some citizens harbor for those who wear the badge.”

In the 21st century, Holder said policing justly and fairly is “working to ensure that everyone who comes in contact with the police is treated fairly.”

The federal crime drop is an ironic exclamation point at the close of a summer that saw a spate of incidents in which law enforcement directed its deadly aggression at African-Americans as if the entire nation were in the midst of an epic crime wave. But, in reality, all forms of crime have steadily plummeted.

Many observers have been puzzled in recent years why the incarceration rate hasn’t plummeted with the crime rate. Among the reasons pondered was self-preservation — law enforcement and the criminal justice system had a vested interest in locking up as many inmates as possible in order to justify their existence. But apparently that trend is changing.

Just last November, according to NPR, the federal prison population was projected to stay level in 2014, with nearly 219,300 inmates. But instead the numbers went down.

“This is nothing less than historic,” Holder said, addressing the NYU School of Law conference hosted by the Brennan Center for Justice. “To put these numbers in perspective, 10,000 inmates is the rough equivalent of the combined populations of six federal prisons, each filled to capacity.”

Holder said that since the crime rate has dropped along with the prison population, “longer-than-necessary prison terms” don’t improve public safety.

“In fact, the opposite is often true,” he said.

Including state and local prisons, the total U.S. prison population in 2012 was about 7 million, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, which was a decline of about 51,000 compared to the previous year. The overall correctional population has declined for four years in a row.

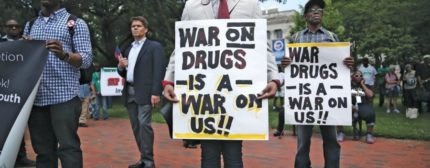

Holder has made it a major thrust of his tenure at the Justice Department to transform the way the U.S. sentences convicted felons. Recognizing that the mandatory minimum sentences have had a disproportionate impact on African-Americans, Holder last year instructed federal prosecutors to stop charging many nonviolent drug defendants with offenses that carry mandatory minimum sentences.

The Justice Department this year has been encouraging more inmates to apply for clemency, and has supported reductions in sentencing guideline ranges for drug criminals that could potentially apply to tens of thousands of inmates.

“We know that over-incarceration crushes opportunity. We know it prevents people, and entire communities, from getting on the right track,” Holder said in New York.

Holder also said the government needs new ways to measure success of its criminal justice policies beyond how many people are prosecuted and sent to prison.

“It’s no longer adequate — or appropriate — to rely on outdated models that prize only enforcement, as quantified by numbers of prosecutions, convictions and lengthy sentences, rather than taking a holistic view,” he said.